The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word “integrity” as a “firm adherence to a code of especially moral or artistic values, and the quality or state of being complete and undivided.” Integrity is not a learned value, and is not culturally determined, but derives from a strong sense of self, and trust in one’s own imagination and intuition and the knowledge that we are, as the dictionary describes, all connected, complete and undivided.

I have been teaching a survey course on the history of world art for almost 15 years, and I find increasingly that while the subject of art is essential to understanding the nuances and beauty of the living world, more and more the violent legacy of our human history must be accounted for, especially in terms of the idea of responsibility and “personal integrity.”

What is integrity in art and how is it represented? Can a painting reflect integrity as its main subject matter, and if so, how is this accomplished?

Each semester I spend a week discussing works of art that are not represented in the textbook. Most of these works are from younger artists whose creative negotiations encompass a wider playing field as it relates to class, race, gender and personal identity. It’s always a red-letter day when I find an artist whose work touches upon multiple elements simultaneously. Art star Kehinde Wiley’s large-scale depictions of Black American men and women blur the boundaries between traditional and contemporary modes of representation.

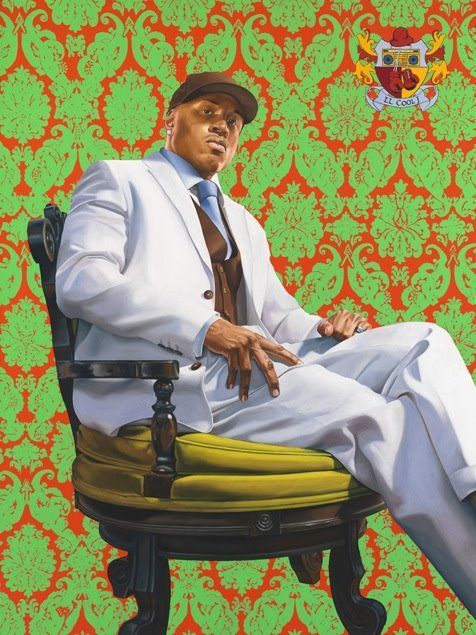

LL Cool Jay by Kehinde Wiley.

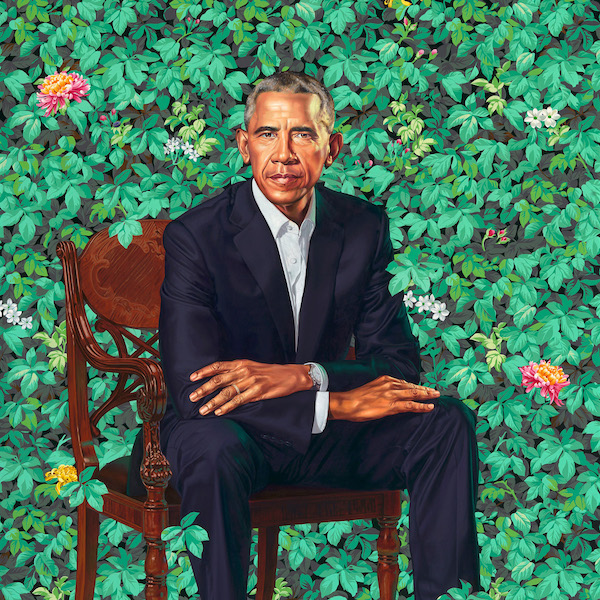

On the surface, Wiley’s images celebrate Black identity, but within every image there is a negotiation between the sitter and the artist, and between the artist and the viewer. Sometimes these negotiations are more overtly honorific, as is the case with Wiley’s luminous portrait of President Barack Obama; yet with this portrait in particular, Wiley allows Obama’s own inherent elegance, poise and integrity to take center stage. There’s an ease established between Obama and Wiley, one that extends outward to the viewer; a permission as it were to be completely authentic and unapologetic. Integrity is born of authenticity and Wiley’s portraits not only capture the variegated personalities of his sitters, but also an intensely realized sense of self—the self of the sitter, the self of the artist and perhaps many of the selves that viewers bring.

This notion of the self transcends gender, political ideation, social standing and seemingly all other boundaries. With the Obama portrait, Wiley is painting a cultural figure whose innate personal integrity defines him both as a leader and a man. Obama is surrounded by lush green foliage, his feet firmly planted in the earth while his gaze challenges us to look at him with the same intelligence and curiosity that he reflects back at us. Still other portraits are similar: Consider LL Cool Jay in his clean white suit, his inimitable style and insistent gaze. Each of these portraits demands that we as viewers meet the subject’s gaze with our own. This kind of connectivity is what gives these images their power. The fact that these figures are empowered and dignified and exemplify integrity means that we are also empowered and dignified, adding to our integrity just for having seen them.