Twenty-one years ago, Katherine Sherwood suffered a brain hemorrhage that left her without the use of her right hand. As described in a 2012 article she wrote for the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, when she eventually returned to her studio, her practice shifted dramatically. Out of necessity, she learned to paint with her left hand. She also reported feeling less self-conscious and able to make more “urgent” connections; whether these changes resulted directly from the stroke (as posited by neuroscientists), the work that followed this life-altering event was infused with heightened lyricism, sensitivity and color.

Sherwood’s solo exhibition at Walter Maciel, “The Interior of the Yelling Clinic,” features works from her recent “Venuses” and “Brain Flowers” painting series, as well as an installation of 10 mixed-media figurative works from her 2010–12 series, “Healers.” Images of the brain appear throughout, and while the artist had been using brain imagery in the early 1990s before her stroke, here, they refer back to Sherwood.

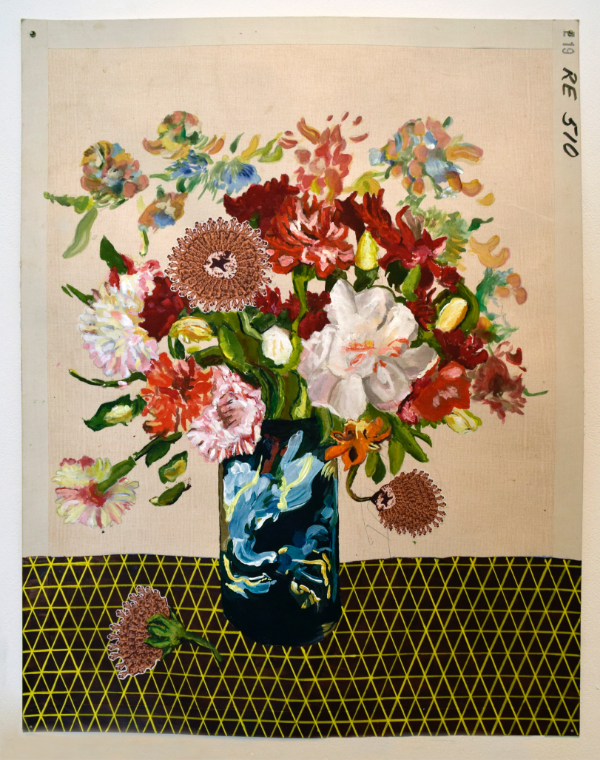

Katherine Sherwood, Chrysanthemums (2017) photo by Aubrey Rubin, courtesy of Walter Maciel Gallery, Los Angeles

The 10 mixed-media figures in “Healers”—constructed from abstract painting, clothing fabricated specifically for this series, painted neurological images based on the artist’s brain scans, and digital prints—function as portraits of a sort. They purvey an open narrative structure counterpoised with a tactile materiality. Sherwood’s handling of paint in these works is wonderfully fluid and sensuous. Shifts in texture from printed, painted and sartorial elements are reflected in the construction of each work. For example, a smooth, yet crack-suffused meniscus-like paint-pour overlaps the embroidered seal adorning the raw linen canvas in Angelo (2012). In Stevie (2011), quilted pants hang beneath the torso and face of an inquisitive-looking young man who wears a kind of top hat filled with what appear to be radiographic images of blood vessels.

In her “Venus” series, Sherwood complicates the treatment of the female figure in Western art, composing reclining nudes after iconic ones by Manet, Ingres, Giorgione and Goya; but Sherwood’s are painted as a critique of the sexualized ideal—the faces of her Venuses comprise her own brain scans and each is depicted with a physical disability that references her own experience of post-stroke paralysis. Olympia (2014) wears a leg brace, After Ingres (2014) a prosthetic arm. Blind Venus (for G) (2018) has a red-and-white cane, Maya (2014) a walking cane. Each of the paintings is made on the backs of several smaller canvases that are stitched together to form a larger whole. On the reverse side are art historical reproductions, once used as lecture illustrations, with unpainted areas of the Venuses still retaining reference numbers linked to master painting images.

In her mining of art historical references, and merging them with allusions to her own medical history, Sherwood asserts a critique of idealized beauty as propagated and reinforced by master paintings created by and for men. Instead, she posits new images of supremely confident women with the composure and power of Olympia, who have moved beyond the confinement of “the ideal.”