For someone brought up within a more or less secular Roman Catholic culture, living now (atheism aside) essentially as if she were a nun, one would think I might know something about “Vespers”—the title of Justin Liam O’Brien’s current show at the Richard Heller Gallery. But I can scarcely imagine these kind of services practiced in modern times by anyone but clergy, and then only as a cure for insomnia.

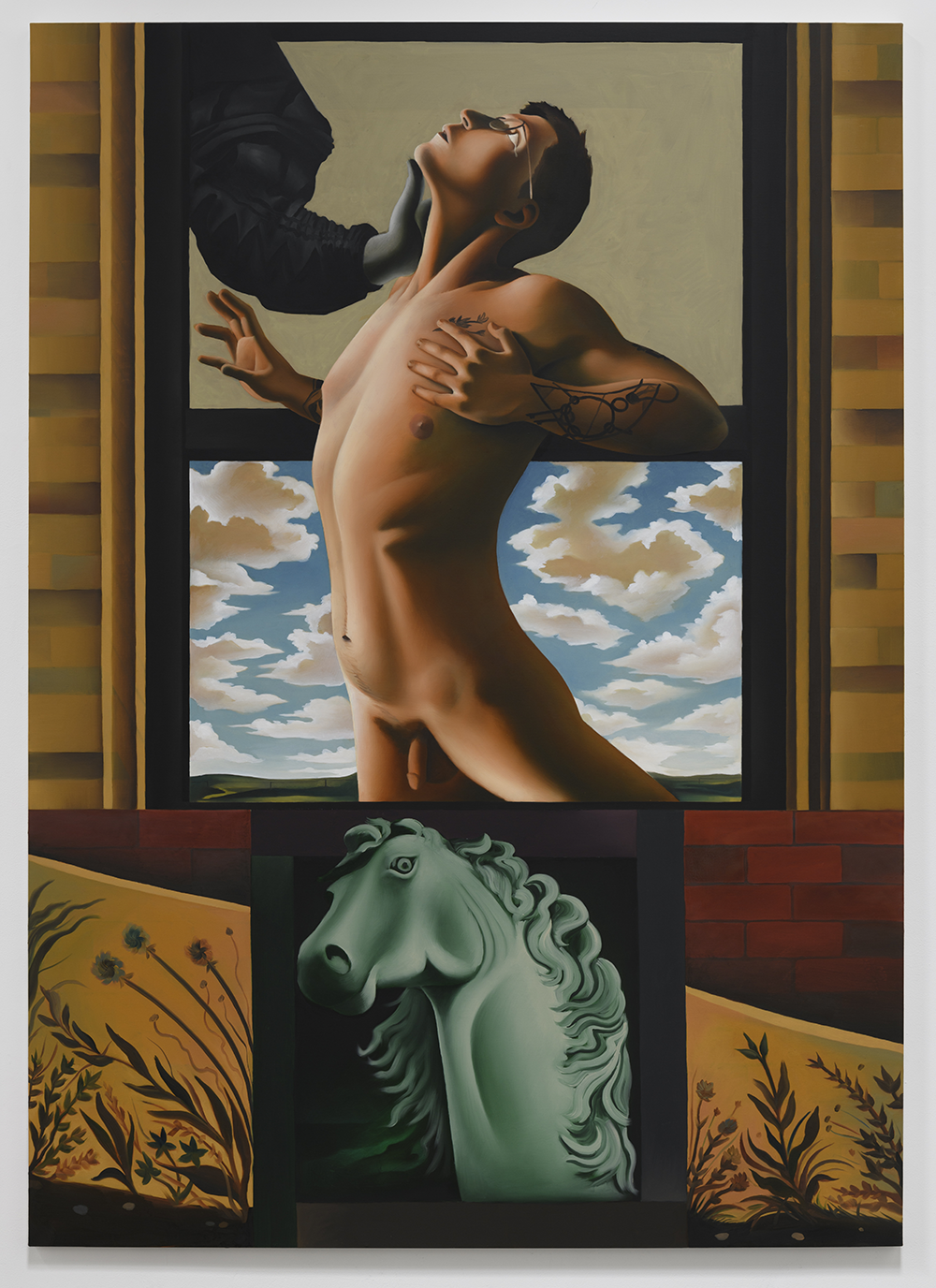

Although any quasi-religious or devotional aspect to his subjects must be viewed as deliberately ironic, O’Brien’s style has evolved both technically and stylistically—attenuating and sharpening what was once a rounder and Léger-loopy (almost cartoon-like) figurative contour, and moving in a distinctly surreal direction, along the (not always spiritual) lines of, say, Leonora Carrington. But O’Brien takes a more distinctly hard-edge approach to his contours, extending even to atmospheric effects, more or less in keeping with his Quattro-cento Italian Renaissance inspirations. Even the explicitly transected paintings in this exhibition—e.g., Hands of Providence (all works 2022)—have the effect of separate planes or panels—very different from Carrington’s subtle dissections and excavations. The full range of O’Brien’s technical virtuosity is on display in Hands of Providence, from its stagy apprehension and notional (if undersexed) ecstasy, spatial counterpoint, slightly schematic atmospherics and aspirational poetics to its quirky details (the figure’s specs) and its scale (at 7-feet in height, the largest in a show of large works).

Justin Liam O’Brien, Vigil, 2022. Courtesy of the Artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

But, as in say, Peter Shaffer’s Equus, true believer or not, there can be no redemption for our clear-eyed seeker of—what exactly?—a guile-free “way in?” (Yes—that’s actually in one of the titles); “unconditional love?” (ditto); “sanctuary?” cultural (or maybe environmental?) renascence? Doubtful—at least under the flattened terms presented in these visions (or vigils?). The implied narratives are amusing but disingenuous. That haunted lover in Vigil isn’t waiting, much less praying for the ghostly swimmer in the nearby moonlit waters. The tech-sleek architecture tells us as much. Guardian angels are one thing; a big bail bond is quite another.

In Adage, O’Brien messes entertainingly with both mythology and style-chronology, slipping in a distracted Carravagio-esque Gen-Z’er carrying a glowing handheld device beneath a large swan predictably annoyed by the switch. In true Carravagio-esque fashion, mayhem and violence proceed apace some distance directly behind the figures. A different kind of mischief is afoot in The Bottom of Heaven, where flattened geometrics compete with discrepancies of scale and expression. Here, a red ladder rises off-center from a red plateau, while a Quattrocento surf shop denizen sits mournfully astride a white horse or pony, roughly the size of a large dog, in foreground waters, abutting a suspiciously sheared embankment. Neither love nor prayer will take this pair any higher.

Far more successful, both formally and narratively, is O’Brien’s recasting of the Annunciation. O’Brien has an outstanding facility for commingling figures within variously composed interior and exterior spaces. But here he’s exploded scale and perspectives, launching his messenger clad only in carmine shorts up and away from a similarly russet-hued pavilion as if he were leaping onto a skateboard, ready to hurl himself into the ether. A similarly out-of-scale raven presumably bestows her blessing—as Piero della Francesca himself might have if he’d known anything about skateboarding.