To read a novel is to play detective. The detective novel leverages this symmetry: the reader identifies with Sherlock Holmes’s or Philip Marlowe’s driving curiosity. Our favorite sleuths want to get to the heart of the crime; we want to get to the end of the story.

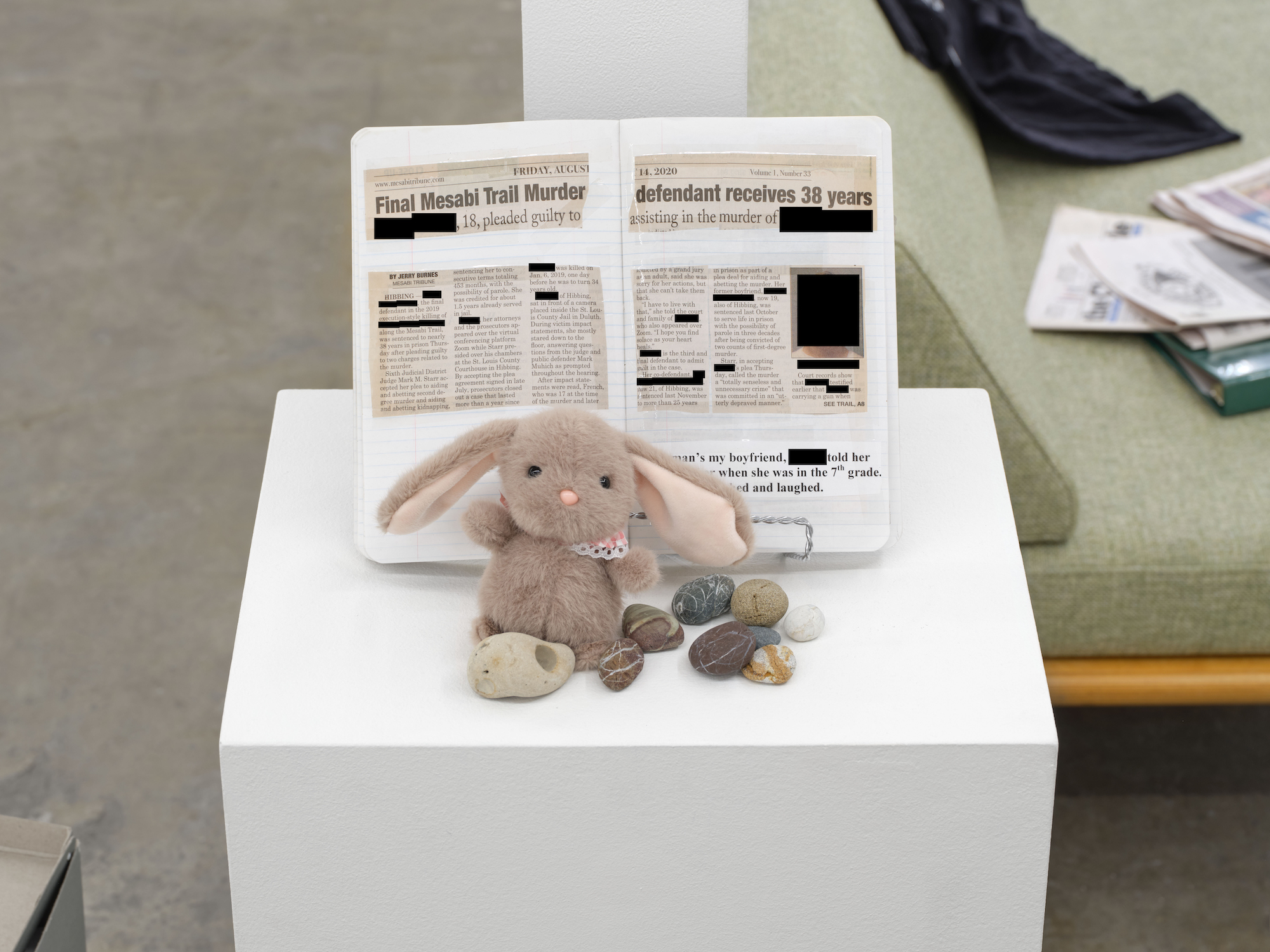

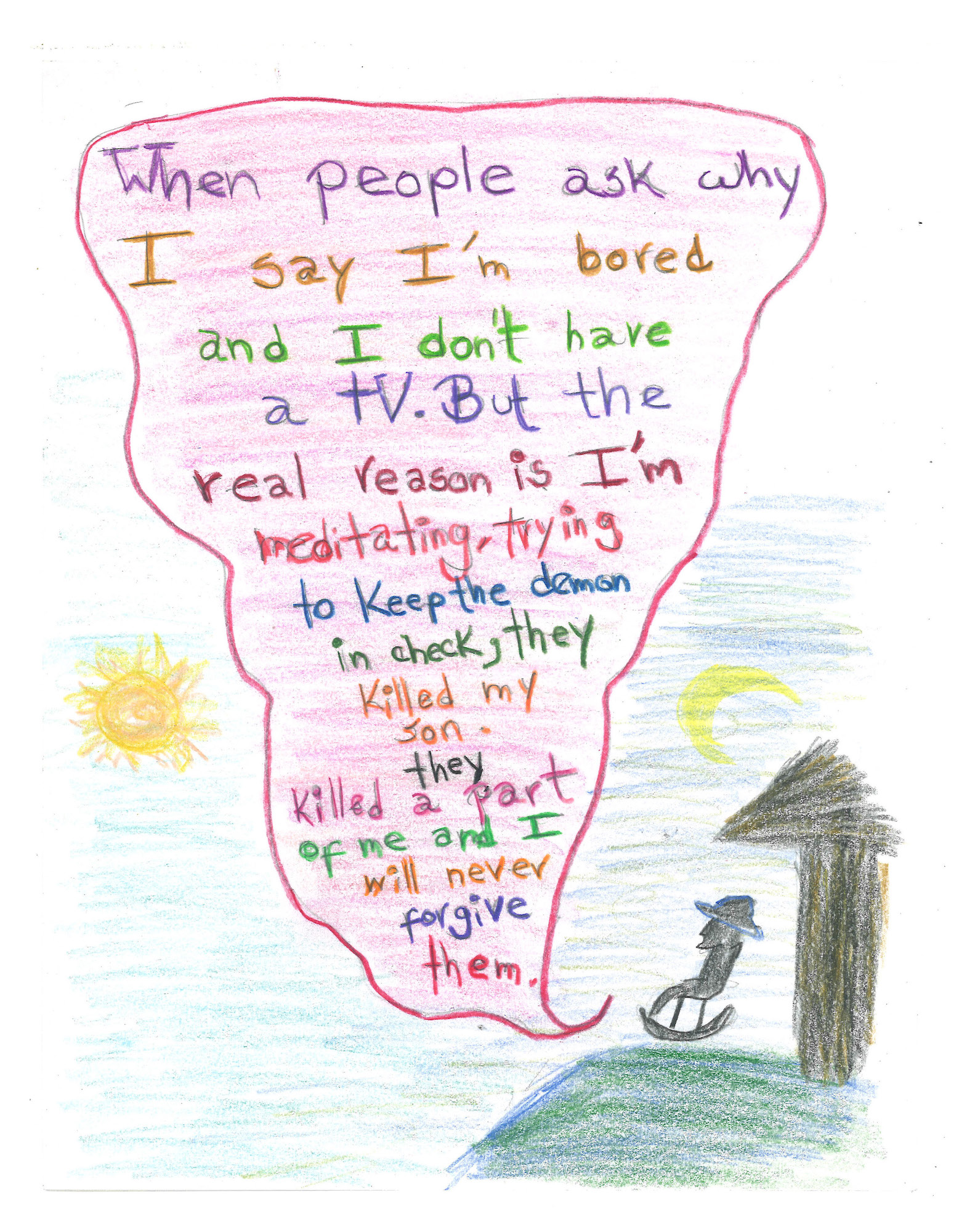

Chris Kraus doesn’t write detective fiction, per se, but her recent exhibition at Bel Ami—a two-person show with Juliana Halpert—fills the Chinatown gallery with volumes of macabre crime research the artist/critic accumulated while writing her forthcoming novel, The Four Spent the Day Together. The novel’s protagonist obsesses over a gruesome small‑town murder similar to a real crime Kraus researched extensively, the 2019 killing of a 33‑year‑old man in rural Minnesota by three kids barely out of high school. “Civil Commitment” mixes legal documents, handwritten notes, screenshots, and other ephemera from Kraus’s investigation with salon walls of childlike drawings by Luis Baez. Baez’s drawings, executed in a refrigerator‑art scrawl, include text excerpts from the research, handling ominously dark phrases with affected innocence.

Interspersed with this archive, Halpert’s photographs make for a deconstructed family album of the artist’s mother, a retired public defender in Montpelier, Vermont. Halpert’s mom (who appears here as a Kraus double, yet another middle‑aged‑woman‑detective) offers viewers a human face to search for the answer to the question: What does it look like to seek justice in the rural American methlands? In a far corner of the gallery, a forest‑drab green frame meant for family photos contains a repeated image of the public defender standing in a parking lot in front of two cars, struggling to read something on her phone as the wind blows hard. Her dark hair obscures her expression. The scene could take place anywhere in America, except that—thanks to Vermont license plates visible in the background and the piece’s title—we know this is the parking lot of a correctional facility in the North Country. In another Halpert photo‑collage, children’s illustrations hang on a fridge in a break room steeped in the institutional green that colors Vermont’s public infrastructure. An overgrown pothos frames a window view of a gloomy, grey day.

The answer seems clear: Getting justice looks pretty inglorious.

Unlike the reader of novels, the visitor to an art gallery should not play detective. To search the exhibition for clues is a Da Vinci Code‑style misstep—an esoteric errand at best, a schizophrenic one at worst. I promise I did not arrive at “Civil Commitment” with my magnifying glass in tow, but after passing through the gallery door (which bore a sign: “NO PHOTOGRAPHY OF ARCHIVAL MATERIALS”) and being cautioned by the gallerist that I shouldn’t read the show so much as absorb it (“it’s more a record of what this kind of project demands,” she assured me), I felt compelled to spend over an hour reading the fine print of every newspaper clipping, journal entry, and flow chart on display, in a mostly futile attempt to connect the dots. The fact that purple Post‑it notes censored names from many of the documents—and that, while I was there, the same gallerist took a phone call to discuss at length with someone (a lawyer?) what else needed to be redacted—did nothing to quell my interest in all the verboten details. I ended up learning a bit about the Minnesota murder, which was committed in the town of Hibbing and involved a lot of Facebook chats. One of the perpetrators was an 18‑year‑old girl named Bailey. But despite my attention to detail, I didn’t arrive at any grand conclusion, just a feeling of mixed dread and nostalgia for a not‑too‑distant past: A series of Facebook memes, gleaned from the murderers’ social media and dated by only five years, felt as old as Hammurabi’s Code.

Visually, the show doesn’t offer much, but the drawings by Baez—which contain select quotes from research, the book itself, and court documents relating to the murder Kraus researched—are compellingly haphazard and emotional and would look at home on the walls of a teen rehab. They add something to the mix, but that something remains uncomfortable, a false yet direct style that feels too forthcoming to be ironic and too ironic to be forthcoming. By contrast, Halpert’s photos—of her mother’s home office, the public defender’s workspace, and the book club meetings in Montpelier—radiate sincerity. Gazing at a digital frame displaying photos of a Montpelier mall, we might mourn adolescence or the pre‑2008 economy. Or basic civitas: A photo of Halpert’s mom’s book club struck me as especially poignant. Vermonter women gather, soft in body and dress, seemingly the last guardians of public ideals. This isn’t cinematic heroism à la Independence Day; rather, it’s the tireless defender tending to a 25-year-old plant in her office.

Kraus’s contribution is necessarily text‑heavy, and it would be an insult to the manifold artists who work with archives (Wolfgang Tillmans, Lorna Simpson, Jenny Holzer, Sadie Barnette, Jill Magid, countless others…) to say “Civil Commitment” makes any significant contribution to the genre, at least aesthetically. The show looks like what might happen if you tried to write a term paper while moving out of your dorm in college—a windowless room cluttered with a bunch of paper and snapshot‑sized photographs, some quickly scrawled and sentimental drawings, and piles of labeled boxes. Plus, you probably need to know who Kraus is and what she has written to be all that interested in the show. But I don’t care, either about the aesthetics or the small audience the aesthetics imply. Frankly, you should know who Chris Kraus is, and Juliana Halpert, too.

There’s something calmingly low‑stakes and mundane about “Civil Commitment,” about how it approaches the specter of crime and violence. We’re reminded that crime tends to be personal in a boring way rather than an operatic way, and that justice, precious as it is, is also boring. In this way, I prefer the show (and all of Kraus’s work) to even the best of Philip Marlowe, because—amid all the irrelevant facts on display—it manages to speak to the truth.