All good crits are alike; each miserable crit is miserable in its own way. Isn’t that the way it goes? We asked a few reliable Southern California university faculty to recommend recent MFA grad students for contributions to our Back to School issue on their critique experiences. We weren’t able to include every school, but here are a few to share with you. As you’ll see, a common denominator is most crits are highly valued, regardless if a negative outcome. Perhaps the dreaded crit is a necessary evil.

CalArtsBeatriz Cortez

In 2006, a New York Times article titled “Tales from the Crit” depicted grad school art critiques as often stressful, destructive, unfair events. This was not my experience at CalArts.

By the time I arrived, the legendary extended crits with Michael Asher had come to an end. Our crits were structured around an idea or a concept, and scheduled as a weekly course meeting, so they had a time limit. However, as before, they were casual, engaged conversations, and not a performance of power. Of course, the crits at CalArts were not perfect but, more often than not, they were constructive. Sometimes they gave me the opportunity to see my work through the eyes of others. Sometimes they helped me understand what the work was communicating conceptually. A series of conversations with engaged interlocutors can give you the tools to control and calibrate your visual language, and I appreciated the depth of these conversations.

My first crit at CalArts was with Leslie Dick. I was impressed by her way of engaging a work of art with her own history, her own body, her own vulnerabilities exposed. I thought she was brave and brilliant, and her conversation set the tone for our crit. I also met other members of the faculty: Michael Ned Holte, Millie Wilson, Harry Dodge, Asma Kazmi, and Charles Gaines, among others. They were intelligent, engaging and generous interlocutors, and I felt fortunate to be there.

School is over, but the community of peers that formed there continues to engage in spirited, insightful conversations.

OTISRegine Rode

“Critique!” A constant juggling between the desire for praise and the hope for a solution. Both aspirations are paralyzing in their aim towards impact on the personal practice.

Critique can sometimes trigger a dreaded debate about one’s own practice. The more you fear it, the more useless it becomes. The graduate critique is a key element of the program and something one can learn from. However, it is completely unpredictable and therefore cannot be prepared for.

Coming from a German Academy of Art, where the class critique is usually structured around a single voice, I value Otis’ practice of having multiple faculty and other MFA students present. This structure usually allows for the student to choose the two faculty members who will be in critique. One critique per term is mandatory, but since the program is small the students have the opportunity to sign up for another one if they wish. The critique is a course requirement and is helpful with learning the terminology used in debates about art. An important part of the process is meeting up with the participants afterwards and discussing what was said.

Sometimes the discussion revolves around something one is not interested in, and then the ability to guide the conversation towards one’s own practice becomes important.

Another helpful facet of critique for me is being an active part of someone else’s crit. Those conversations have always brought up important questions that can be useful discoveries about my own art and process.

UCLAKim Truong

I have participated in six group critiques, each of which was led by a different professor, and each of which was unique. They ranged from predetermined structures to open-ended conversations. In every meeting, the works of one or two artists were presented for discussion. These crits were in-depth discussions of how artworks exist and are perceived in the world. The diversity in experiences and perspectives often added complexity to existing work and at times generated new ideas. For me, the crits were also platforms to understand human interactions.

Each of the three series I presented in my MFA exhibition in spring of 2015 suggested a deconstruction of a fixed understanding established by unquestioned formalities: a sense of unity emerges from a series of fragmented elements. Seriality approaches singularity in a study of accumulation that explores the context in which polarity breaks down established expectations. By making hundreds of similar objects and setting them up to be viewed as a unit, my work deals with the connections between people.

My classmates usually expressed perplexity when discussing my work because it explores the context in which polarity breaks down established expectations. Many of these discussions provided opportunities for me to study the aesthetic attitudes of people and their relationships. I found the graduate critique process at UCLA to be invaluable because each meeting was another opportunity for me to learn about another group’s structure.

Art Center

Owen Dubreuil

Going through the critique process at Art Center was a necessary tool to push my practice forward; a time to confront problems and opportunities in communicating through my work.

In most scenarios, only the students taking the course and the person leading it are included. Critiques take place once a week and last between 90 minutes and three hours. In some cases the artist is required to speak first in front of the work that they are showing. Other times the artist will display their work and not be allowed to discuss, explain or comment at all. The critiques take place in the student galleries or in the individual studios.

In my initial critiques I was immediately confronted with the delicate balance or difficult problem of how an ego interferes with a work. The critique process forced me to let the work be, let go, get out if its way. Elimination of defense was key to this process, allowing the value of the critique to be realized. There is always a critique occurring throughout the program, though each is unique in its particular form. The Theories of Construction course is the one class solely dedicated to the critique.

The value in the critique lies in the willingness of the students to explore their reactions to the experience as well as the feedback given. The process was a deconstruction; a tearing down of what I thought I knew. Will it hold up? What are you saying? It’s about what is even possible to talk about when confronted with a work of art.

UCLATamara Anne Weller

The main UCLA components of the critical processes are the quarterly critique class, graduate reviews and individual meetings with faculty of our choice.

For the graduate reviews, students sign up with several faculty members for 20-minute one-on-one sessions. They choose faculty they currently aren’t working with and are for the most part a meet-and-greet session.

The critique class and individual meetings with faculty proved to be the the most valuable experience for me. The first few meetings with faculty were supportive and generative.

However, my first critique class was a somewhat different experience. I presented a large-scale sculpture for critique and a hurricane of dissent swept me unwittingly into a position of defense. My work had ignited a debate over the legitimacy of myth and poetry in art. The critique class is a more combative environment where ideologies are debated and ideas challenged.

There are some downfalls involved in these critical processes. Students, including myself, often bow down to institutional discourses, reproducing the ideologies and creative processes of the institution.

I think the most important thing I have learned is that students must look inward during the critical process in order to maintain a plurality of voices and ways of working, resisting the homogenization of ideas and art itself. The critique process challenged me to become a stronger self-critic and inspired me to probe the depths of my work and its meaning.

CGUAbdul Mazid

At Claremont Graduate University, the art “crit,” the fundamental incubator, in which ideas could be investigated, honed, revised, scrapped entirely, or pushed to maturity, and in which the discourse centered on the act of looking critically, became the foundation from which all other aspects of the graduate school experience developed. Thus, the most significant result gained from my experience was to refine the act of looking as connected to critical thinking and, ultimately, action.

The formal crit setting—individual meetings with professors, group-crit classes, and studio visits with visiting artists—were frequently supplemented by informal crits provided by interactions among the MFA student body. There wasn’t a specific moment that I can pinpoint as a watershed, but rather the extensive submersion that caused me to realign expectations of a MFA education.

It took me one semester to conclude that the guidance and curriculum of the institution was central but only a partial map to navigate by. I decided to hone the skills that would most crucially help me throughout my career. This meant long hours and nights in other artists’ studios looking, discussing, arguing, defending and encouraging investigations. Breakthroughs were made and unmade. Ultimately, the level of awareness, an ability to look, think, and reason were vital skills born out of the crit process that influenced multiple aspects of my education.

Critique ultimately provided the skills of how to learn. These processes still continue after graduate school, with studio visits from both galleries and fellow artists. The learning continues, as does the process of looking and thinking critically.

USCKathleen Daly

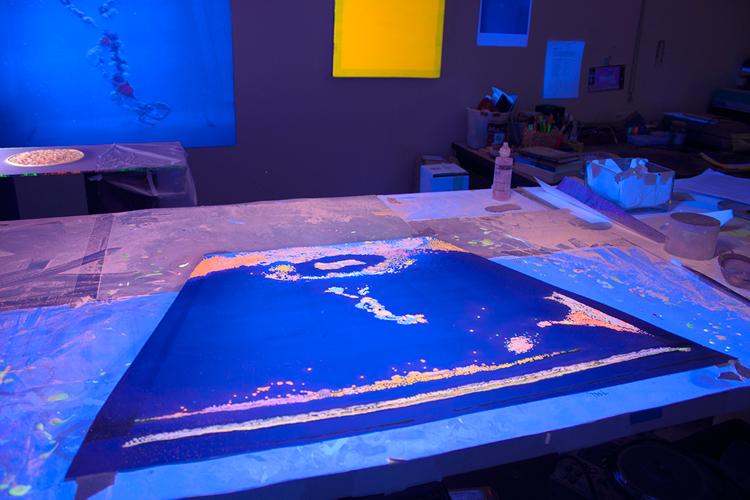

Open studios occur once a year. It felt like a big birthday party my first year at USC. Everyone participated—All 15 MFAs, the faculty, the MA students and friends. We collaborated on the poster for the event, and each MFA student contributed to the image. We also displayed our work in the gallery space, which was curated by two second-year students. The DJ set up in the kitchen after the faculty left.

I panicked when I showed up at grad school, feeling like a misfit with no fabrication skills. When you get there everyone is working, and I wandered in at the wrong speed. It took me a long while to make anything, but confidence in creation is a great energy to be around. Being forced into that studio cubicle is a luxury: it gives you the time to pay attention to the way you work. Open studios force you to share the work and there is a lot to be said for surrendering one’s privacy.

My open studio ended up a disaster, owing to technical difficulties. After I explained the malfunction, the conversation quickly became confusing and weird. That’s the problem with the small studio situations—too much is assumed, but that can also be the wonderful part.

The studios are now empty with no second-year class and only one new incoming student. The years the building opened its studio doors to friends and the public, it was a fantastic celebration of art and its communities.