Joseph Stashkevetch is a consummate craftsman, his work suspended effortlessly between drawing and photography. In his recent show at Von Lintel Gallery, the addition of a literal third dimension leverages his simple process (conté crayon on rag paper) into an instrument that progressively peels back layers of appearance to reveal ever-deeper and more resonant realities hidden underneath.

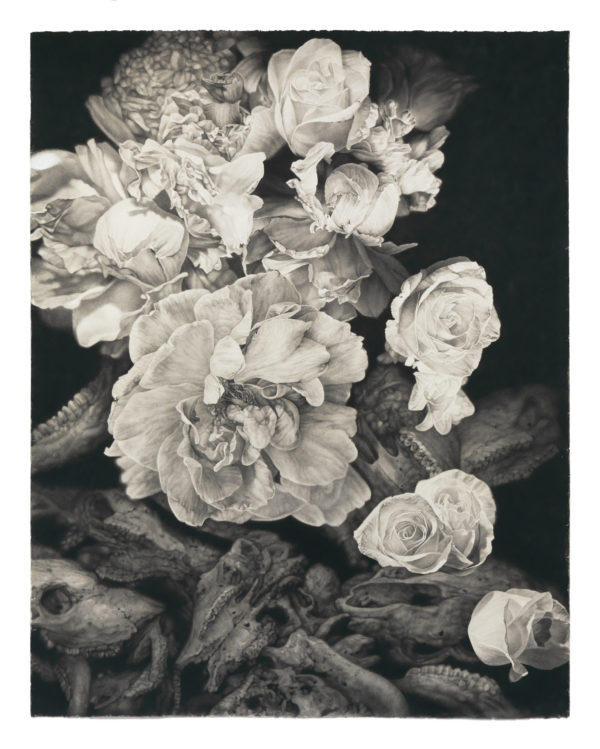

Stashkevetch has clearly mastered the skills of the archivist, and the ironist. In White Flowers & Bones (2015), an explosive floral still-life monochromatically mirrors the brilliant cascades of baroque flower paintings. At the same time, it echoes “the miraculous flowers of Hamburg,” which bloomed in 1943, sprouting from an earth superheated by the Allied incendiary bombs that killed 40,000 while incinerating the city, which G.W. Sebald described in his book The Natural History of Destruction. Nor is a whiff of that death itself absent, rather it is displaced by the artist to a pile of bovine skulls that ground the image and stretch off into the ever-gloomier distance.

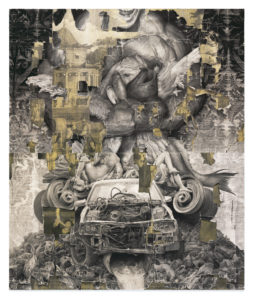

In his more recent work, this compounding of memory and history, of artifice and destruction, of nature and culture, of assertive likeness and apparent reality is only intensified as layers of paper are held flat, crumpled, ripped, sliced, peeled back and weathered to form complex palimpsests of superimposed and interpenetrating images, mini-archives of text and commentary in pictures. This whole machinery is most grandiloquently on display in the monumental All You Can Eat (2016), which reads like a classicizing commentary on the decline of Western civilization (the perfectly centered—if fragmentary—juxtaposition of one of Michelangelo’s Medici tombs above a brutally scavenged and derelict car) as well as a catalog of images and motifs (the skulls, the dead fish, the bird wings, the musclemen) that define the arc of Stashkevetch’s own career.

Joseph Stashkevetch, All You Can Eat, 2016, ©Joseph Stashkevetch, courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery.

At the other end of the spectrum, Torn Curtain # 1 (Blue Roses) (2015) reveals its intimate secrets with an enormous poignancy. In this instance, the “torn [wallpaper] curtain” uncovers, through the process of its own decay, a world beyond, which precisely reduplicates its printed pattern while hinting at its own eventual decay. The artifice and the reality are one.

Stashkevetch’s world is one where Thanatos inevitably outstrips Eros—as, for example, in Amore & Psyche (2016)—and entropy eventually reigns supreme, except in the miraculous Sanctuary (2015). There, it is the central image that overwhelms the viewer: the interior of a long-abandoned Yiddish theater in New York, now pulled down for redevelopment, even as Yiddish culture itself slides inexorably into memory and extinction. And yet, through the punctured roof streams a beam of light, intensely bright, a palpable presence. This is the light that makes things visible, and yet can blind us by its very brightness. It is the light of figuration and transfiguration: the light of Joseph Stashkevetch’s art.