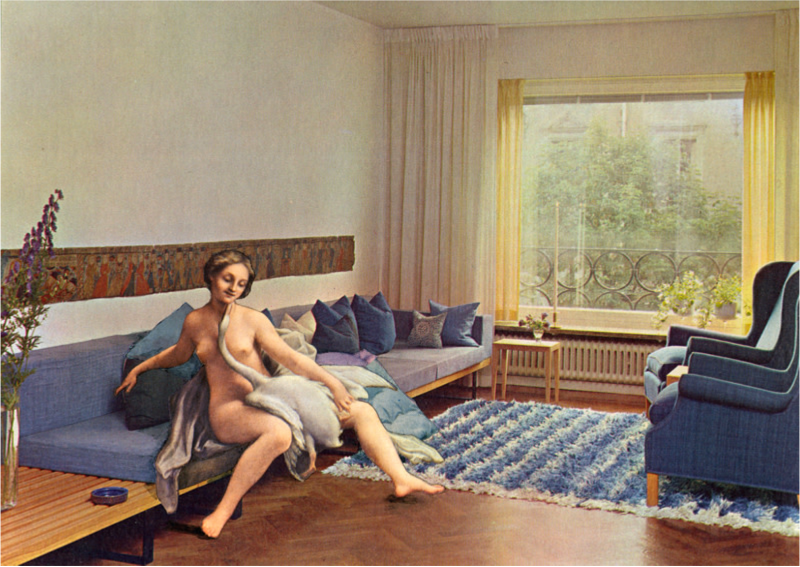

The intimate scale of John O’Reilly’s photomontages belies the broadly ranging ambition and scope of his concerns. The 40-year survey of his work at Zevitas Marcus reveals a consistency of approach spanning the entirety of O’Reilly’s production. The artist, whose work was included in the 1995 Whitney Biennial, began making paper montages in the 1960s, almost entirely with a Polaroid 100 camera acquired in the mid-’80s. His meticulously constructed compositions seamlessly draw together disparate images from varied sources—art historical, printed material, pornography and studio Polaroids—into a nearly continuous pictorial space.

O’Reilly’s antecedents are John Heartfield, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Hoch and other Dada artists—a number of whom claim to have invented photomontage; but his interest in the form is not in emulating the expressly political aims of Heartfield’s early works. Hausmann and Hoch are more closely related in that theirs were open forms, allowing for associative possibilities.

The juxtaposition of images that are clearly discontinuous is smoothed over by O’Reilly’s technical dexterity and intricate process (elaborated in detail in Francine Koslow Miller’s essay, Assemblies of Magic) to create works that initiate a dialogue between literary, art historical and more introspectively personal concerns.

Heartfield’s works contributed to an understanding of photographic media as manipulable, and within that framework, O’Reilly’s montages are examples of the pre-digital plasticity of the medium. Yet O’Reilly delivers his finely conjured fictions with a wink, alternately concealing and exposing the evidence of his interventions.

His process of shooting and re-shooting studio tableau, and then cutting, gluing, sanding and smoothing edges introduces traces of the artist with painters, writers and other figures. A reproduction of Velasquez’ Las Meninas (A Paper Self, 1986) alongside a cutout of his own profile—literally, a trace—puts him in the company of another artist who put himself reflexively within the frame while commenting on the world around him.

Within the montages, he leaves evidence of the construction of his tableau—a Board propping up a picture (Of Cavafy—Swimmers, 2008), or a pair of thumb tacks (Worcester Street Series #2 County Road, 1992), and so on; in addition to the conversation being inflected with the artist’s body, his presence directly or indirectly felt, the works reference the artist’s hand, commenting on their own facture.

This leads to a push/pull between a purely interior and imaginary space created within his concoctions and an indexical relationship to the process, the studio and the self.

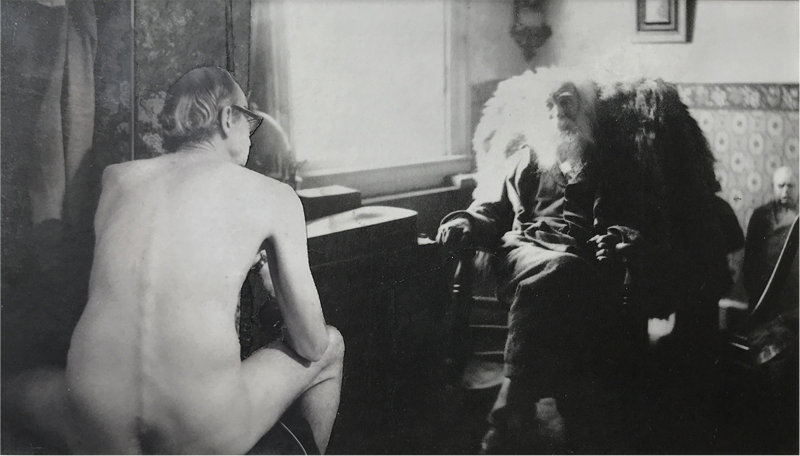

Of these interior spaces, none is more illusionistic than Talking with Whitman (1984), a fictitious portrait of the artist, seated nude on an ottoman, his back to the camera, in conversation with Walt Whitman, evoking the poet’s Song of Myself (1855). Nor is there any that exceed the technical sleight of hand he achieves in this piece, in which he seamlessly blends the space between himself and Whitman, as if traversing time and space, establishing a kinship.

The works here, a mere introduction to O’Reilly’s output, offer a window into the artist’s long conversation with art history and his endlessly engaging interior space.