The paintings in John Currin’s show at Dallas Contemporary, a non-collecting warehouse museum, widely induced a queasy, unsettling tension. A common response to the artist’s work, the visceral repulsion and simultaneous attraction result from an unresolvable friction between the paintings’ typically dreadful subject matter and the sensuous, masterful (a word I use advisedly) paint handling. One is drawn to the paint but repelled by the imagery.

John Currin, Homemade Pasta, 1999, courtesy of Gagosian.

At its best, Currin’s painterliness is extraordinary, if retardataire, not seen anywhere in painting today. In style and often subjects, Currin’s evocation of the “old masters” reminds us of the historical association of painting with male artists, which led many feminist artists to discard the medium. Effortless passages of gestural brushstrokes enliven Currin’s paintings with restrained bravura. In contrast, three-dimensional forms in the paintings are often smoothly modeled by gradations of soft color, in which the brush is palpable. In places, his convincing depictions of fabrics and fur are tactile, felt as much as seen. As a figure painter, Currin employs a facile, often sinuous—some might say elegant—draftsmanship, especially in postures and gestures. However, his misogynist or pornographic subject matter is decidedly distasteful. Proffering an alternative to the sexualized female figures for which Currin is known, this exhibition devoted to male subjects invokes a similar grotesquerie, fallibility, and pathos. Men will be men and nothing can be done about it.

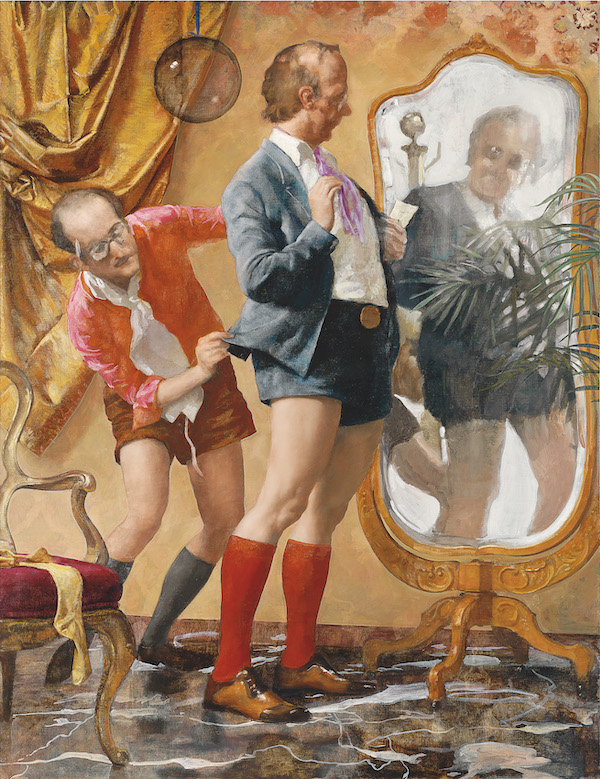

John Currin, Hot Pants, 2010, courtsey of Gagosian.

The big-breasted or nude women featured in Currin’s paintings would seem to appeal to masculine fantasies expressed by the objectifying male gaze. By focusing on his paintings of men, Alison Gingeras, an adjunct curator at Dallas Contemporary, counters his politically incorrect reputation with an argument for his incisive exploration of the “gender politics that animate our fractious sociopolitical moment.” Despite Gingeras’ deserved reputation for challenging the canon and conventions of painting in past exhibitions, her interpretation, supported by catalogue essayists Naomi Fry and Jamieson Webster, of “My Life as a Man” as feminist because the male subjects are fops, fools, or sad sacks is barely convincing.

John Currin, Office Workers, 2002, courtesy of Gagosian.

Representing four decades of work, the exhibition included some revelatory early portraits of men with wide, staring eyes ringed with exaggerated, cartoonish black eyelashes. As blatantly adolescent kitsch, they expose the artist as a self-conscious provocateur. Less convincing than the paintings themselves is the process argument in the catalogue that many of Currin’s men originated as portraits of women (with long eyelashes?) and thus express a sympathetic transsexuality or at least gender ambiguity. Currin’s narratives are also marshaled in support of the “#MeToo” movement. Office Workers (2002) literally illustrates the subject of workplace harassment, depicted in a glorifying style of thick oil paint, luminous highlights, and a heavenly background of blue sky and puffy clouds. Like a dirty joke—Currin refers to the influence of MAD Magazine throughout the catalog—this tiny, approximately one-foot-square canvas, requires close inspection, a voyeur’s apprehension of a man and woman sitting at a desk with a computer screen to the side. Her elongated bratwurst-like breasts are plopped on the desk while he reveals an impossibly extended penis.

Installation view at Dallas Contemporary, including The Kennedys (1996), The Dream of the Doctor (1997), amongst others.

The Kennedys (1996) is a double portrait in which the bodies of a girl and boy have identical heads representing JFK. The flesh of the ruddy faces is repellant, rough and bumpy, the result, according to Currin, of applying paint with a palette knife to simulate the impressionistic, Rodin-like surfaces of the ubiquitous bronze busts of President Kennedy that Currin knew as a child. The softer, brushed application of paint, particularly responsive to the depiction of light, and more nuanced use of color in The Dream of the Doctor (1997) are typical of Currin’s sensuous, most tender style. Although the subject is jokey—a seated doctor leans into a folding screen on which a lacy brassiere hangs—the pale shadows cast by the furniture and the flesh-like rendition of the surface of the flesh-colored screen (standing for the concealed female patient) are as seductive as the narrative pretends to be.