John Altoon couples his relaxed, entirely convincing painterly hand with a flippant disregard for norms whether social, societal or artistic. His retrospective at LACMA cavorts, galumphs and saunters through a wide variety of styles, approaches and modes of image-making that astound for their vibrancy and their prescient lack of concern for modernist confines of working in a signature style.

Ranging from abstraction to figuration, Altoon seems equally at ease with either. This large but not overwhelming selection of painted and drawn works is taken from his fine art practice, as well as some of his modified advertising boards, and delves into numerous of his outrageous sketches. This allows the viewer to circulate liberally through the ideas and images knitting together Altoon’s complex, variegated and whimsical world. Adroitly arranged by curator Carol Eliel in a primarily a chronological order, the different rooms concentrate on distinct portions of Altoon’s output and offer an implicit interpretative key to his participation in the artistic, historical and societal chapters of his time.

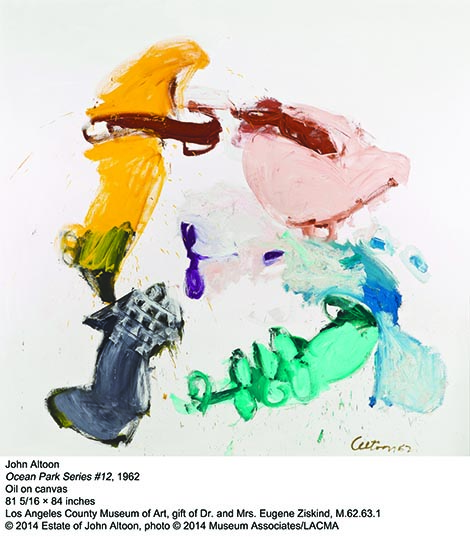

Links between the quirky, erotic and downright odd forms he colors and conjugates underscores his freshness and his singular interpretative axis. Occasionally seeming to echo other artists—biomorphic abstraction in the vein of Arshile Gorky or muscular gestural slathering along the lines of Willem de Kooning—Altoon retains a strain of poetic reverie that keeps his works operating along their own lines. The color gamut runs from bold tertiary colors to unusual combinations of dark and light, often with the negative space etching forcefully into the composition. He dabbled with airbrush, mixed drawn-line and painted line, scrambled and splattered with abandon and a paradoxically deft sense of control.

Altoon walked a tight rope between oppositional formal components without dropping into irony or placing his tongue in his cheek. The visible evidence militates for his belief in the power of art even without the categorical imperatives at work in high modernism. If his artwork seemed funny, it was in an elegant and highly refined way, or in a sharp and critical mode.

In an oil painting such as Ocean Park Series, #12 (1962) the fierce abstraction operates on the vaguely phallic and vaginal forms, the interpenetration of shapes and colors in space, the loosely defined almost haphazard negative white and off-white back drop all colliding in magical cohesion and self-sustained clarity. Altoon does not give anything up to a logically or linguistically determined meaning. It is, all at once, a landscape, a sentiment, a paean to sex, and homage to painting in the raw.

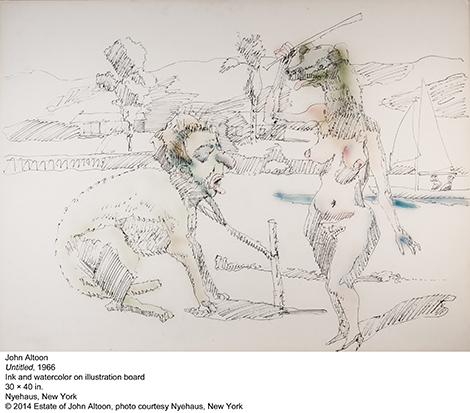

In Untitled (1966)—a pen, ink and watercolor drawing on illustration board—Altoon’s attitude towards sexuality and the role of gender comes more directly to the fore. Tied by the neck to a stake in the ground, a dog sporting the head of a gaping, gasping middle-aged man pulls back at the rope with a suspiciously erect tail between his legs. In front of him, a very curvaceous naked woman’s body surmounted by the head of a panting wolf or fox raises a stick in the air over the dog/man’s head. All of this takes place in an idyllic setting with tract houses and a sailboat in the background.

Aside from his art, Altoon’s life was the stuff of urban myths: returning to his birthplace in Los Angeles after a tour in the Navy, life in New York and Europe, he joined the artists exhibiting at Ferus Gallery in 1956 when everything hip and cool was on the rise—jazz, the sexual revolution, America’s urbanization, and the rising film industry. Altoon jumped in with both feet, teaming up with jazz musicians, ending up as poster man for the Beats and marrying the movie star Fay Spain. He also suffered from mood swings (manic depression or schizophrenia) severe enough to have him hospitalized repeatedly. Between his art, the external art world phenomena and his rather big personality, Altoon was a significant presence on the LA art scene. That he died of a massive heart attack at the age of 43 in 1969 turned his life into a kind of tragi-heroic docudrama.

What is wonderful about the exhibition at LACMA is how, notwithstanding this quasi-legendary status, Altoon’s art lives up to any expectations a viewer might have for it. Original, wholly convincing and incredibly exuberant, his images participate in the world around them and yet set themselves off as unique, individual creative adventures.