Johanna Breiding’s show of photography and ceramics at Ochi Projects defied singular characterization in favor of an enveloping tsunami of empathic correspondence—a tidal progression of images both intimate yet nothing less than oceanic. The exhibition’s slightly coy title, “Playing Submarine,” hinted more at Breiding’s narrative strategy, leading the viewer’s eye through brief image sequences that pushed larger perspectives alternately skyward and into a kind of collective unconscious with a pendant moment of self-confrontation.

The images were all tightly framed, self-contained, specific. The first, a vacuum hose spiraling out of a deck-side hole and into a pool’s turquoise water, bore the title, Imago (all works 2020 unless otherwise indicated), to which both psychoanalytic and entomological meanings might easily apply. Crown, the second image in this sequence—a bald head emerging from a pool of water, the diffracted lower body visible beneath the surface—completed the “imago.”

A glossy glazed black ceramic cat identified only as Vessel 57, provided a potent pause in the procession of photographs (digital C-prints, mostly color, but several in black and white), its open mouth echoing the preceding crowning, while signaling its communication with the installation as a whole. The next sequence sustained these motives of emergence, communication and containment: a deep recession in a snowbank against an alpine landscape in black and white; followed by color images of milk dribbling out of an open mouth; boiling milk bubbling stovetop from a small pot.

Johanna Breiding, Home, 2020, courtesy of Ochi Projects.

Following a more chromatically intense visual pause, Breiding seemed to fold her subjects into the frame, including her own tightly locked left elbow and knee (Self-portrait with scars); a communion and confusion of the subjects’ respective fur involving a dog’s harness and a cleanly sectioned thicket of infinitesimally interweaving branches (Crutch).

The placement of the largest image, a mylar sheet stretched across a shimmering body of water (Second Skin), was a reversal—a shedding of skin for the aquatic domain, celebrated in the gallery immediately behind it. There, the balance of Breiding’s ceramic “vessels” (including a lobster, a sea turtle, sea snail and seahorse amongst other creatures or their shells) variously glazed in blues, white and sea-green, were gorgeously arrayed upon a long table. Against the wall, nine ink-and-charcoal drawings of body fragments and organs both human and aquatic, played like shadows of the hollowed vessels on the table.

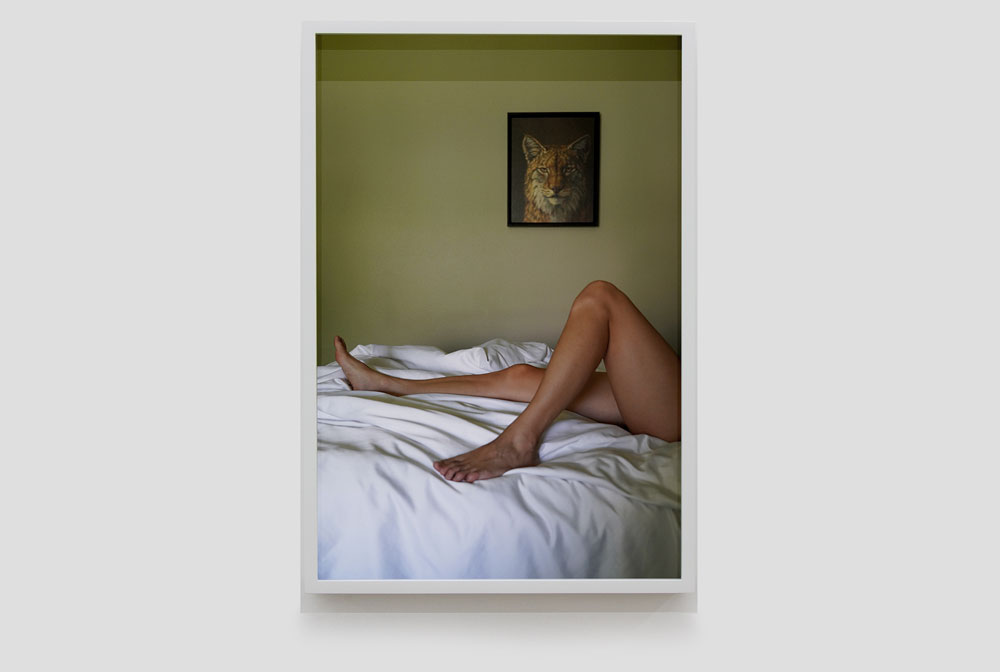

Breiding’s final images tested the limits of legibility while climactically complicating the larger exhibition narrative. Home was a paper construction peaked, folded and creviced into a floating mountain; Cloud 9, a dark curl of cumulus cloud billowing into the sunlight, oculus to a space without limiting definition. The viewer’s gaze was finally met head-on in a small painting of a bobcat hung just off-center to the rear of a bed foregrounding a nude body’s bended knee in Apex, which seemed to sum up the contradictory juxtapositions of legibility and actuality—the ferocity underlying the vulnerability.

0 Comments