Jim Shaw’s work has always moved, both performatively and analytically, between the quotidian space of individual consciousness, and collective and cultural spaces both conscious and unconscious. Since he began using film studio and theater backdrops as readymade support surfaces, his work has ventured more aggressively into both cultural politics and the mythographic foundations of Western culture—and by extension, the unconscious. The title for the show, “Thinking the Unthinkable” (an abbreviation of Herman Kahn’s 1962 Thinking About the Unthinkable, about hypothetical nuclear war and its aftermath) hints at this even as it underscores the artist’s ambition. Yet Shaw continues to draw heavily from the imagery of Western commercial entertainment—both comic book heroes and mid-20th century Hollywood film studios.

The most fully realized of the works here—where dream fragments seem to cohere into a unified field conjoining the undercurrents of human consciousness with the mechanisms of commercial culture—are Shaw’s acid dream studies and full-blown oil/acrylic portraits of mid-20th century Hollywood film stars (Esther Williams, Jeff Chandler and Cary Grant), and a couple of the larger works where the Hollywood promotional dynamic meets a disruptive political culture now evolved into its current pathological state. His 2019 pencil study for the larger oil/acrylic The Bay of Pigs Thing (2022)—with its naval amphibious landing gear disgorging frolicking starlets amid a wave of movie-cheerful military characters just ahead of disparate 1960s television icons (onetime NBC Tonight Show host Jack Paar and JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald)—may be one of his finest drawings. The more panoramic (48 x 77 in.) oil/acrylic rendering sets this “landing” over the crest of a tsunami-like wave cracking Washington’s Watergate Hotel in half. It could be read as a vision of the political Establishment cracking beneath the open floodgates of global cynicism, mistrust and distraction, yet Hollywood itself continues to traffic promotionally in these kind of tongue-in-cheek images.

Jim Shaw, Down By the Old Maelstrom (where I split in two), 2022. Photo: Jeff McLane. © Jim Shaw. Courtesy of Gagosian.

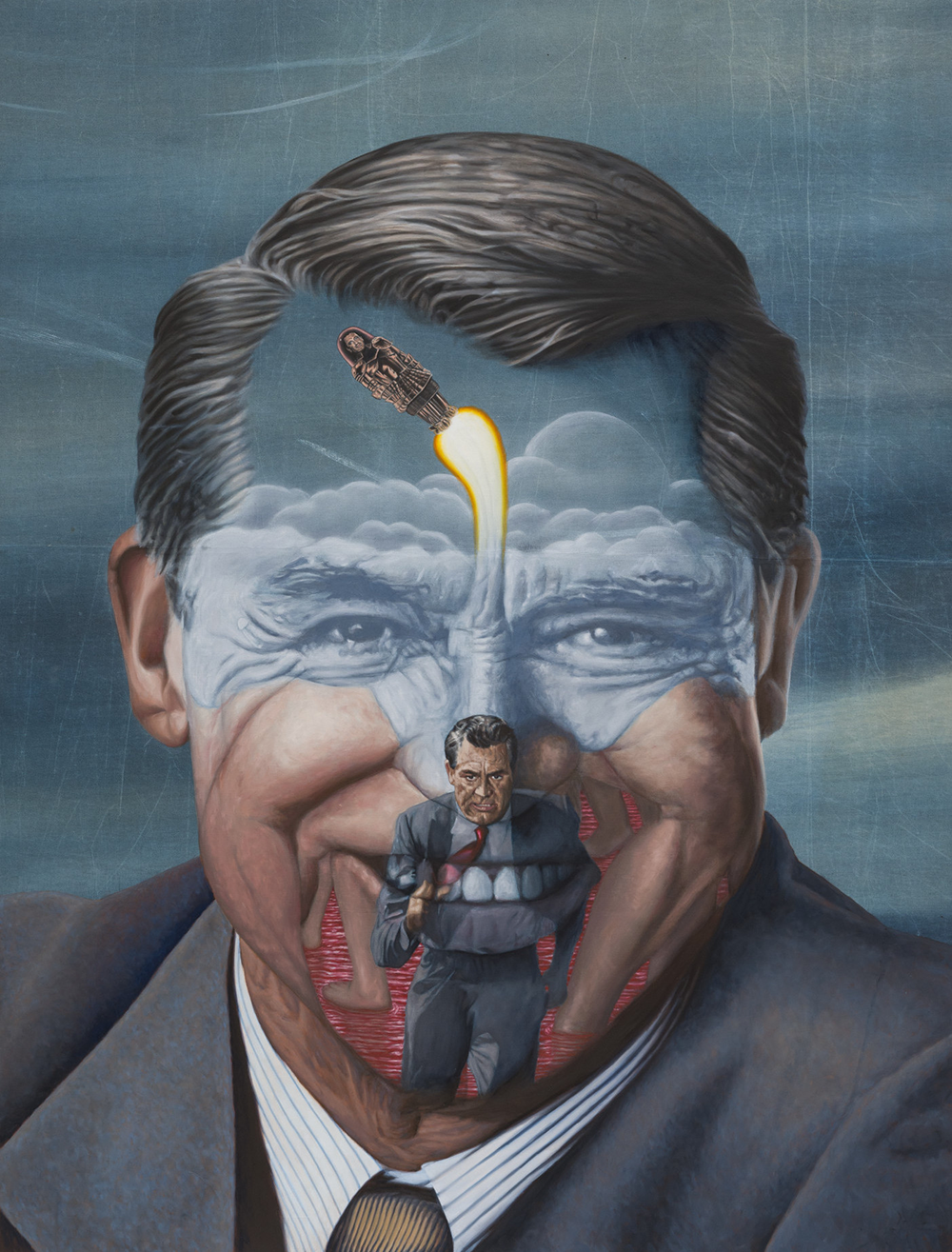

Shaw deconstructs a classic Hollywood portrait of Grant (drawn from his North by Northwest incarnation) into a Dali-esque landscape of infant legs suspended over pooling blood through which an inset figure of Grant runs more or less as he did from the cropduster in the film, while a capsule-scale Grant-bot is launched in full armor into the stratosphere of his LSD-fired imagination. Chandler’s and Williams’ more photorealistic portraits are in turn inset with images of dreamed androgynous or hermaphroditic concepts of one another.

Shaw comes closer to giving some foundation (or at least the 20th-Century Fox pedestal) for his theoretical speculations regarding a fatally flawed or abandoned matriarchal civilization with Going for the One (2022), merging Raquel Welch as she appeared in advertising for the 1970 film of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge, with some aspects of the sometimes ambi-sexually represented Hindu god, Shiva. The four-armed Welch/Myra/Shiva/Bhikshatana is conspicuously under-armed here, yet her doomsday capabilities are apparently enough to bring down the Century City twin towers—whether for sexual betrayal or budget overruns (an iconic image for Fox’s 1960 Cleopatra advertising campaign appears on the north tower) is unclear.

Shaw buries the real “unthinkable” here in his 2022 The Egg and I—paying tribute, not just to the book (and film), but the characters (based on real people), Ma and Pa Kettle—and their 15 terrifying children. Hollywood writers, directors and producers were “thinking the unthinkable” long before Kahn and The RAND Corporation. Alas the world’s many “Kettle children” are willing to play out such scenarios all the way to Doomsday.