The first work one sees upon entering Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s solo exhibition at Anat Ebgi is a monochromatic print of the ocean—the hazy sky fading endlessly into the sea like a Rothko color field painting. The print offers a moment of reprieve, the calm before the storm, before thrusting forward into the multi-sensory explosion of colors and forms in You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me.

The common threads through Huffman’s work are unflinching sincerity, vulnerability and a slight sense of cynical humor. The prints and videos read like visual poetry of someone’s diary—messy and complicated, abstract yet cohesive. Huffman is an artist whose work is actively saying something and is most clearly commenting on the black experience in the United States. There’s a sense of urgency and chaos, with the video works displaying scenes of explosions, car accidents, the daily mishaps of modern life. Murphy’s rule seems to hover over the snapshots of reality that Huffman offers—everything that could go wrong will, and it seems, already has.

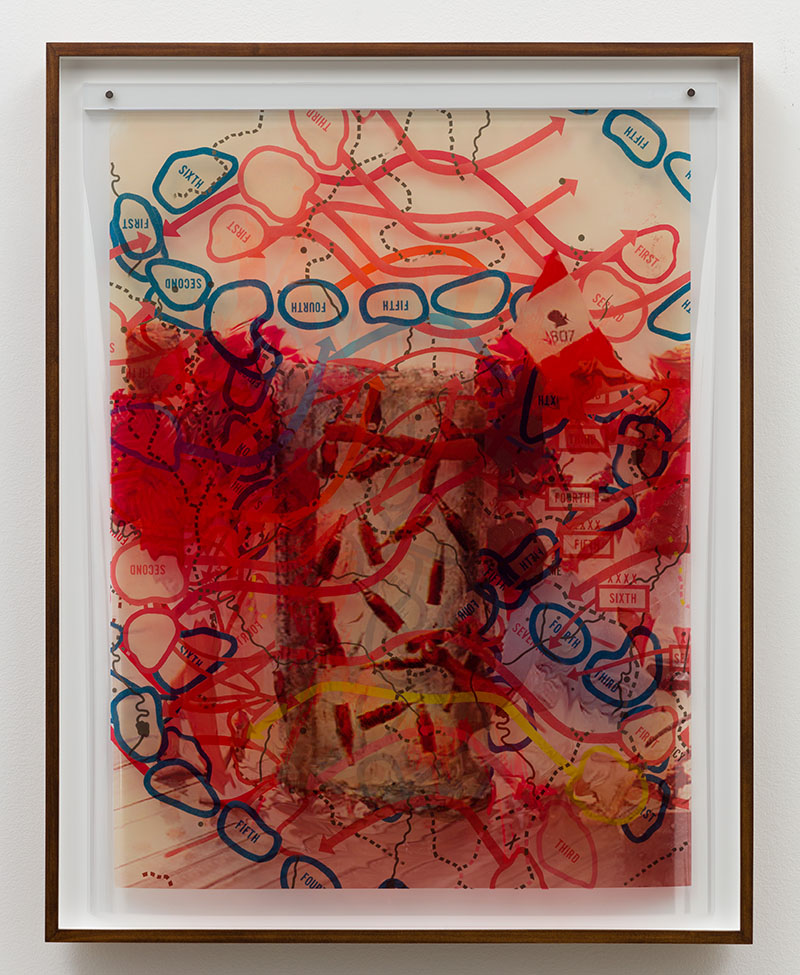

Jibade-Khalil Huffman, Untitled (Florida Sign), 2019, courtesy Anat Ebgi Gallery

Pop culture and modernity reign in Huffman’s world, with many works featuring an anthology of images from modern and post-modern life—with Lichtenstein-esque renderings commingling with newspaper cutouts of phrases like “murder weapon”, “Detroit”, and nods to jazz. In Map (2019) and Future (2019), inkjet prints are layered on transparent plastic. The two works appear both old and new, the 1970’s aesthetics coalescing with modern themes, creating a sort of vintage futurism and perhaps offering a nod (or more) to Afrofuturism. The two video works in the exhibition, The Price of the Ticket (2020) and Zero (2020), are a cacophony of sounds and images, at times projected through an abstracted limited view. The videos are, in many senses, uncomfortable, with grating sounds and quick-cut edits that often showcase the chaos and dystopia of city life. Huffman offers what appears to be a behind-the-scenes view of a variety of things, from explosions to traffic to car crashes to fire trucks going off to battle. I found myself wondering how Huffman was able to acquire the video snapshots—it seems that he was often in the right place at the right time. The videos captured the daily life of regular people, faces that are often absent within art spaces. Without psychologizing the artist too much, the videos do offer a view of the world that is at the very least, troubled, and the influence of the internet is not lost on the viewer.

Huffman’s exhibition doesn’t follow a linear storyline, the works instead forming a larger collage and visual poetry of big concepts like modernity, the black experience, and nostalgia. The artist kindly offers a solution to the hectic noise with Untitled (Florida Sign) (2019) and Untitled (The Sea) (2019), two snapshots of nature that have an air of peace and tranquility. The interconnected duality of these two works with the rest of the exhibition creates a larger sense of Yin and Yang—a balancing act that complements the chaos without negating it.