In his recent work, Jesse Benson uses appropriation to dismantle “appropriate” interpretation. But unlike other painters who might pursue this goal through dramatic, even offensive subject matter, Benson does something subtler, de-familiarizing recognizable, seemingly benign imagery. Ultimately, his paintings reveal the fragility of knowledge. While this may seem a profoundly complicated endeavor (and it is), you wouldn’t know it from a quick glance at the work. In fact, Benson’s paintings need and deserve sustained mental and visual attention because doing so pays off quite well in the end.

Benson’s most successful works are part of his ongoing “Repainting” series, images appropriated from sources outside the confines of art history, particularly professional illustration. Benson copies his source imagery with impressive exactitude, often down to each brushstroke. This fidelity and technical skill are purposefully enticing; the works seduce in the way only meticulously rendered painting can. But once you’re in, you start to question what and how you see.

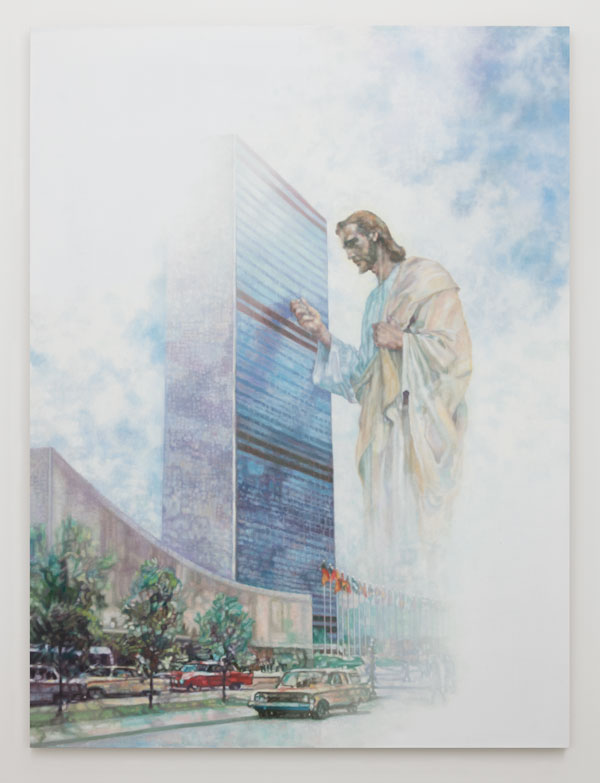

Jesse Benson, Repainting 5 (Prince of Peace), 2017, courtesy Michael Benevento, Los Angeles and the artist, photo by Jeff McLane.

To make his work, Benson strategically alters each appropriated image to question how what one sees aligns with what one knows. For example, in his painting Miracle Grow (all works 2017), we see what appears to be a picture of a gigantic Anglo-fied Jesus Christ knocking on the UN headquarters, a well-known and quite surreal image by the American illustrator Harry Anderson. But something is off. Benson has enlarged the picture to many times its original size and dissipated the image on two of the canvas’ opposing corners. Upon closer examination, it’s apparent that in the process of blowing up Jesus Benson lost some of the original image’s detail. This slight alteration shifts the image’s previous, obvious and direct message to a much less stable register. Miracle Grow is different enough from its referent to resist being mistaken for something devotional. On the other hand, Benson’s alteration isn’t quite dramatic enough to read as an overt criticism of the religiously charged evangelical original. Because of this liminal signification, interpretation is treacherous; the painting won’t settle down. As earnest Christian kitsch, it looks out of place in a contemporary art gallery, but it would be equally strange in a church. In fact, it’s hard to imagine Miracle Grow hanging anywhere it wouldn’t frustrate, making any context it occupies subject to scrutiny.

In Prince of Peace, Benson repaints a jovial image of Santa Claus by an unknown artist but shapes the area around St. Nick into the edges of an angular, symmetrical, snowflake-like abstraction. It’s a familiar, understandable and banal image with the illustrative source acting as a blank slate. Santa is so iconic; it’s possible to take his signification for granted. Benson turns this image into a kind of Rorschach test, compelling viewers to analyze what they see in the abstract form. It’s odd searching for meaning in an image so familiar. In essence, this painting exemplifies what’s at the heart of Benson’s “Repainting” project, namely understanding the difference between what something looks like, what it is, and knowing what it means.

0 Comments