Jeff Koons consumes five floors for the Whitney’s last show on Madison Avenue, and no wonder. Surely the artist who installed a giant floral poodle twice in Rockefeller Center can fill every nook and cranny. No one else takes such pains to rub in the obvious, to shock, and to please.

Andy Warhol played the innocent in a disaster area, the scene of car crashes and electric chairs. Koons is the sophisticate in the candy store, ready with whatever it takes to keep a basketball submerged in a fishtank. He is also a brand name. As sponsor for the retrospective, H&M announced a new Fifth Avenue store and a limited-edition Balloon Dog (Yellow) handbag. Yet in Koons’ body there is not an ironic bone. People write him off as a cynic, and they are wrong. He wants everyone to laugh along with him, even when things get nasty. And he wants ever so much to please, which starts with pleasing himself.

Koons had his breakthrough at the New Museum in 1980 with his series of upright vacuum cleaners in transparent display cases, “The New.” As readymades, they have little subtext. What can one expect from a vacuum-cleaner salesman? At the same time, a vacuum with its switch off seems airless. And nearby these in the Whitney show lie a snorkel and an aqualung, in bronze.

Koons gained more attention in the East Village in 1985, with his “Equilibrium Tank” basketballs floating just below the surface. They are still unsettling in their simplicity. Then he abandoned readymades for polychromed wood and porcelain in the late ’80s. The “Banality” series includes Buster Keaton on an ass, angels leading a pig, and Michael Jackson in that awful gold suit, cuddling a pet chimp, Bubbles. Jackson may derive from a Pietà, but a dead Jesus never sat so upright.

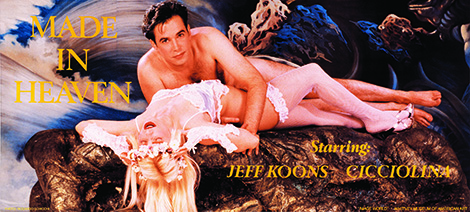

For “Made in Heaven” in 1994, Koons posed with Italian porn star Ilona Staller, whom he married. Here photorealism loses its detachment and its virtuosity, for who knows what the artist contributed, beyond the toned body and the sex?

He must have enjoyed more the idea of being married to a porn star than the actuality, for the marriage soon ran its course. So for the most part had his art. He throws down his “Hulk Elvis” paintings as if to infantilize Warhol once and for all, and classical sculpture interrupted by suburban lawn ornaments, but little more.

A sculpture completed this year, Play-Doh (1994–2014), required removing the museum’s doors to get it inside. It follows Claes Oldenburg by representing the everyday while alluding to tradition—here the loose volumes of early Modernism. And yet those volumes are crumbling into a gross-out.

The curators could have opened in the Meatpacking District with Koons, using the museum atrium for his puppy. Instead, they will devote the new building to the collection, followed by an African-American artist, Archibald Motley, and a living classic, Frank Stella. They are still turning their back on great architecture, but there is no happy way to say goodbye.