Inter Milan, an Italian football powerhouse, recently endured another racial incident. It is common for Italian fans, and other football teams’ supporters, to throw bananas at Black players on opposing teams. This latest insult, however, came not from fans but an on-air football analyst. When discussing the impressive play of Inter Milan’s Belgian striker Romelu Lukaku—born in Antwerp to Congolese parents—the analyst suggested the player was so powerful that the only way to slow him down would be to throw “him ten bananas to eat”. Clearly, a single banana would not do. This is not an Italian peculiarity: one can find similar actions taken by the British in Bill Bufford’s book, Among the Thugs, which features scenes of football hooligans moshing at a National Front disco night. The Children of Ham deserve all they get, it appears—Even an American President has been demeaned as the cartoon monkey Curious George, predictably eating a banana.

In the work of the Nigerian/Scottish artist Jebila Okongwu, the symbol of the banana becomes particularly fruitful; as a corrosive sexual stereotype, as a metaphor of incarceration and bondage, and as a symbol of corporate piracy, exemplified by the United Fruit Company and Dole.

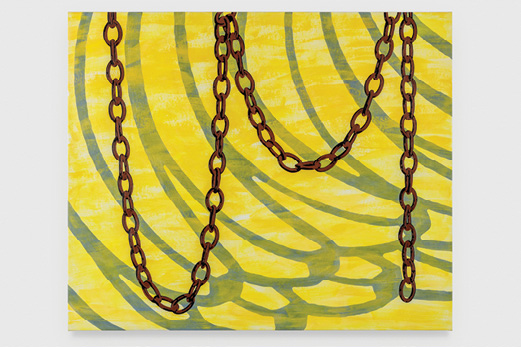

Jebila Okongwu, Painting for Los Angeles, 2019, courtesy the artist and Baert Gallery, Los Angeles.,photo by Joshua White—JWPicture

Bananas are referenced throughout, in stylized illustration or text works, in variably sized paintings or constructed objects, by mimicking banana shipping boxes. The paintings also feature a chain motif of not just shackles but ships’ anchors. The chain (rusted, bloodied?) in Product of Cameroon (all works 2019) is so subtle that it takes a moment to appear; similarly, with Premium Bananas (Study). The links in these chains are essentially footprints, traceable not only to the pillage of human cargo but to goods: the ore, the diamonds, the oil, the fruit. Simba (Study) suggests that Hollywood continues to profit from Africanized confections, notably, Simba, the princeling in Disney’s The Lion King.

The oversized fruit boxes are particularly striking, (Five Banana Boxes).They mimic genuine corporate packaging design (French, Compagnie Fruitière; Italian, Fratelli Osero) with perforations to aerate the fruit. Over six feet high, one stack three boxes tall, the other just two, they are scaled to contain not fruit but humans. Peering inside reveals bondage gear, a suspension harness and a human cage.

Might such prolific usage of the banana increase its vulgar symbolic power? The answer can be found in James Baldwin’s short story, Going to Meet the Man, about a Southern sheriff who is unable to satisfy his spouse. It is only when recollecting a lynching that he can perform his husbandly duties. Brutality is not only profitable, it is also erotic.