“A Cold War,” Jamison Carter’s current solo exhibition, and his second with Klowden Mann, revisits dichotomous themes introduced in his 2013 solo exhibition with the gallery, in which he explored the tensions that exist between man’s pervasive desire for advancement and the limitations of space-time. The artist resumes his ongoing material exploration with the disparate forms that appeared in his previous show: brightly colored, precisely drawn lines juxtaposed against black, amorphous shapes executed on paper, and sculptural planks, colored in neon hues and bundled together into nebulous forms made from painted plaster.

O Superman (all works 2015), a 6-foot tall, coffin-shaped wooden structure occupies the center of the show. Carter’s meticulously drawn, vibrant lines cover the painting-cum-sculpture. The inescapable reference to abstract stripe painting is subverted by Carter as he reinterprets the genre. The “stripes” look instead like perfectly cut slices of solid pigment that have been glued together, reminiscent of works from the late 1990s when a number of Los Angeles-based artists were experimenting with paint as medium, isolated from its substrate, to produce layered, sculptural works.

O Judge, spatially oriented as if in response to O Superman, sits huddled in a shapeless heap, resembling a black, meteor-like mass. The antithesis of O Superman, it symbolizes the organic world in its most basic manifestation. Viewers may question Carter’s choice to borrow the opening lines of Laurie Anderson’s 1981 recording “O Superman” to name these two works. However, by using a quote that references the opening lines of Massenett’s 1885 opera Le Cid, “Ô Souverain, Ô Juge, Ô Père,” Carter uses the allusion as a signifier to convey a resignation based on the cyclical nature of evolution, a reoccurring theme throughout the show.

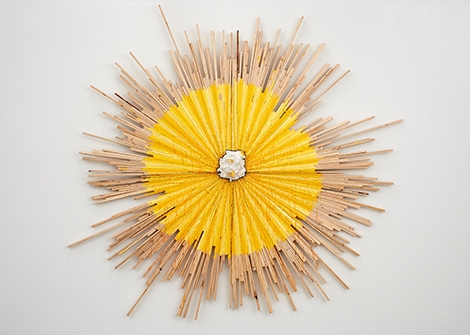

Sol, the largest sculpture in this series, spans a 10-x-10 foot-space. The wall-mounted work best expresses Carter’s shift from a calculated and mechanical approach towards an application that is fluid and allows for chance. A composite of wood, hydrocal, paint, glue and hardware, Sol elaborates upon the topic of surrender, its materials chosen for their capacity to change with continued exposure to the elements.

Two additional sculptures in “A Cold War” integrate wooden shards that, like Sol, provide a nod to the Baroque. Each work’s sun-like projections not only reference Bernini’s gilded rays from Ecstasy of St. Teresa, they also call to mind the formation of ideas set forth during the 17th century that conceptualized a new way of thinking about nature based on reason and the analysis of physical laws.

The show’s remaining works emphasize Carter’s inclination to experiment with materials that encourage extemporaneous malleability. Of particular note are four framed monoprints that aggregate paint, hydrocal and dirt. Collectively, they exemplify Carter’s intrigue with process by setting up parameters that allow for undetermined outcomes. These, coming from an artist whose meticulous hand was a constant throughout his previous series, are not only compelling, but also reveal the transformative spirit that relinquishing control can impart.