Even in December, the trees on Delancey Street have a coppery glow. It is not the glow of fall foliage, not on a Lower East Side thoroughfare better known for traffic than for signs of life. At least one gallery has bricked up its glass façade to keep out the sights and sounds.

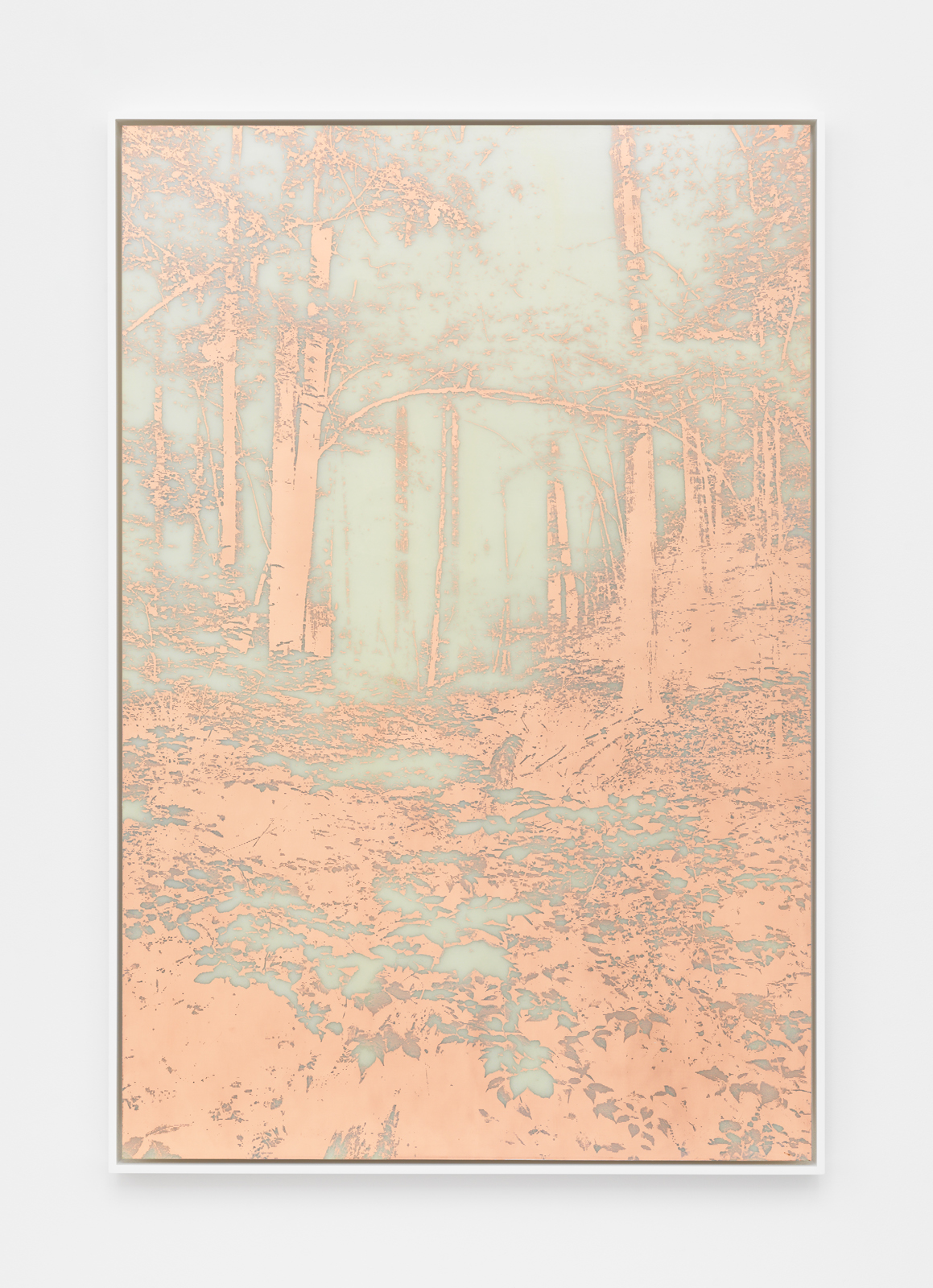

No, these trees exist only within a work of art, and this copper is the real thing—the transition metal, the 29th element in the periodic table. James Hoff etches it on fiberglass, to evoke the silhouettes of trees. It outlines trunks, leaves and branches with a delicacy and density that would defy many a landscape artist. Then again, Hoff borrows the technique used to create microelectronics.

He brings more of nature into the gallery as well, so that it, too, takes on the appearance of a landscape. Mottled stones lie here and there on the floor. They look natural enough that visitors may already expect some trickery. Perhaps he cast them in foam, for the mere illusion of stone. Yet once again they are the real thing, only this time the reality of the found object, give or take a little help. He has painted them black and white.

James Hoff, Useless Landscape No. 39, 2016, courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts.

They promise an enclave apart from the city, but beware. Hoff calls the show “Utopia Landfill, or Vacation in the Age of Sad Passion”—and it does not sound like a recommendation of where to escape the coming winter. Of course, others, too, have wondered where the inorganic ends and where life begins. Garret Kane, for one, has embedded electronic circuits into carvings that evoke schools of fish. This artist, though, is not in awe of the digital. When he looks forward, like Sophia Al-Maria at the Whitney, he sees toxic waste from used devices and a cramped imagination. He makes a point of having started with photos of the great outdoors taken from a cell phone.

Hoff’s ambivalence toward humanity and nature also extends to art. He begins with the conventions of landscape painting, and he compares the technique of etching circuitry to screen prints. Copper has its place in art history as well, as an alloy with tin: sculpture in bronze all but invented the Renaissance with The Gates of Paradise by Lorenzo Ghiberti. Hoff also models his black-and-white stones after camouflage, and he notes that artists created those patterns during World War I. He does not mean it as a compliment.

Maybe, though, he should—or maybe he understates how much he already does. Maybe he knows that, all along, living creatures have depended on copper to carry oxygen, much like iron in humans. Maybe he knows, too, just how much he evokes landscape painting. Even as Useless Landscape, the tracery on fiberglass glows with autumn, and the stones carry it into a third dimension. Art often thrives on the border between nature and culture. Now it just takes on appropriation and the digital.