With her “Untitled Film Stills,” Cindy Sherman played with the idea of the Hollywood sex symbol; she disappeared into one role after another, showing how art and film noir convention could collude to create sex appeal from the trappings of innocence and repression—and from the beauty and implicit dangers of dark shadows, startling camera angles, the open road and the American city.

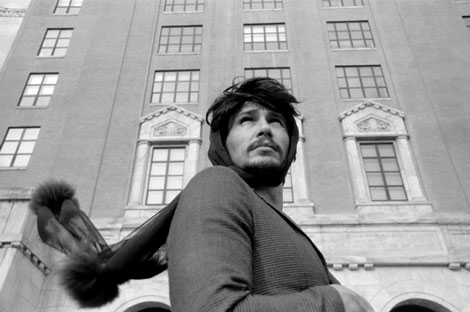

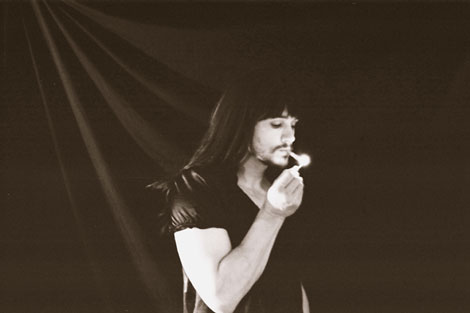

Now a genuine sex symbol restages Sherman. For his “New Film Stills,” actor/teacher/poet/artist James Franco adopts her poses. Opening-night crowds lined up down the block for a glimpse of him in person. But he never showed up.

Is he daring or dutiful? Franco brings out Sherman’s tart assault on the manufacture of gender by posing in drag, in that same clothing from the 1940s Sherman used for the working-girl next door. Yet he comes perilously close to a comfortable one-liner.

He has also managed to generate more outrage than the entire Pictures Generation and then some. Here he was, the angry story circulated—just another powerful male appropriating a woman’s sexuality.

Would Sherman, though, have claimed in the first place to have taken back the frank expression of sexuality for women, rather than underlining its artifice and undermining its assumptions? (She did her best to shrug off the whole affair, although she wondered aloud how the exhibition ever found its way to Pace.) And unquestionably, Franco is serious in trying to break out of his assigned part. He has studied writing, filmmaking and fine art at prestigious schools and is completing his PhD in English at Yale. He wrote Frank Bidart for permission to adapt a poem and found a mentor and a friend. The poet, in turn, wrote an effusive (and slightly embarrassing) catalog essay for the new show.

Seriousness, though, has its limits, especially when the subject is the social construction of the serious. Someone coming to Pace without catching up on the controversy in advance would surely smile in recognition at the show’s title—and maybe even identify a couple of photos as after Sherman. The marvel is how few. And then the problem is what that leaves for Franco.

He did his homework with the costumes. Yet the scenes do not match all that well, in part because they never could. Sherman, between 1977 and 1980, was revisioning the deep past, and the urban landscape has not stood still for those 35 years. Yet somehow she evoked one era while fashioning the reigning fiction of another, while Franco’s backdrops seem arbitrary and flat. And that just leaves a muscular guy posing in front of them.

Franco wants to submit himself utterly to his cross-gendered part while claiming it as his own—because art is like that in its perplexity, including Sherman’s. He ends up instead front and center. The star of Oz the Great and Powerful once again steps out from behind the curtain, and looks wanting.

Images courtesy of Pace Gallery