In Irene Hardwicke Olivieri’s Subterranean Family (2013), a large woman crouches, her body sinking into the earth, weighed down by a patchwork of introspective self-images. One curls in a sphinx-like pose, her feline tail circling behind her back, as she clutches a stack of mail to her side. Below her, another doppelganger huddles, fetal, her body striped and furred, as miniature figures suckle at her chest. A tall, striding woman boasts long legs in explorer boots, and a red suitcase labeled “Misterios de Familia” (family mysteries) in her left hand. A fourth woman puts her arm around an owl and teaches it to read. Skeletons rummage through a closet. And in the lower right-hand corner, a nude figure reaches down to outline roots with her paintbrush. A tree rises from her mark, winding above the horizon to shelter the larger crouching woman.

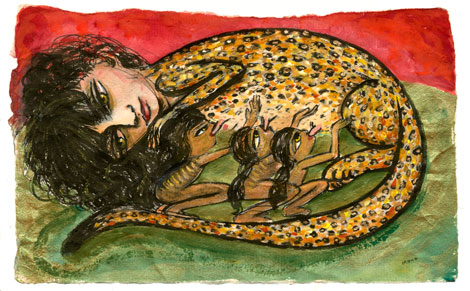

A casual viewer might think the drawings, paintings and bone constructions resemble fairy tale illustrations, but Olivieri is not dealing with any ordinary fairy tales. Girls suckle from the teats of large wild cats, and in turn offer their breasts to lion cubs. The god of nature is a male giant whose torso is tightly enmeshed in verdant foliage. Little girls carry the entire imaginings of a society in their Rapunzel-like hair. The loss of species is mourned, and the discovery of new ones celebrated. A woman whose face, hair and body are composed of tiny bird bones kneels on a rusted dustpan and holds up the sky.

Indeed, Olivieri’s depiction of the female-nature connection resonates in intriguing transgressive ways. Women and animals are both on the bottom of historic hierarchies (men/women, human/animal)—which means they both occupy the territory of the Bataille abject. And yet both are needed desperately if we are to save this planet from total degradation.

In the intriguingly surreal content, the autobiographical focus (all of these dark-haired beauties resemble the artist herself), and the fine, precise drawing, Olivieri’s work recalls the work of Spanish Surrealist Remedios Varo (1908-1963). There are specific parallels: Olivieri’s image of a woman painting a tree into existence evokes Varo’s Creation of the Birds from 1957; Olivieri’s repeated use of feline imagery echoes Varo’s, especially in paintings like Paraiso de los gatos from 1955. But beyond that, Olivieri—like Varo—celebrates woman’s creativity, woman’s oneness with nature, and the ever-valuable strategy of knowing and imagining the world by knowing and imagining the self.

Olivieri’s Retreat (2013) depicts a woman standing in a cage of bound branches. She is nude except for a tool belt crammed not with hammers or wrenches but with drawing implements. More paint brushes and pencils, these wildly oversized, crowd around her, similarly imprisoned in the leaf-dense enclosure. The intense green of the sky promises fertility rather than threat. Is she trapped by nature? By her creative efforts?