Two weeks after the exhibition “Thomas Joshua Cooper: The World’s Edge” opened last fall at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The New Yorker magazine published a piece by Dana Goodyear titled “The Ends of the Earth: Thomas Joshua Cooper risks his life to photograph the world’s remotest places.” Goodyear’s profile is a page-turner because Cooper is quite a character, as was apparent at a LACMA preview when he and museum director Michael Govan led a tour of the show. Cooper began by comparing his travels to Ferdinand Magellan’s 16th-century attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The reference is relevant because the polar north and south where Cooper has photographed are as unexplored today as oceans east and west were in Magellan’s era. From Magellan’s “expedition,” Govan says, “Cooper has taken inspiration.”

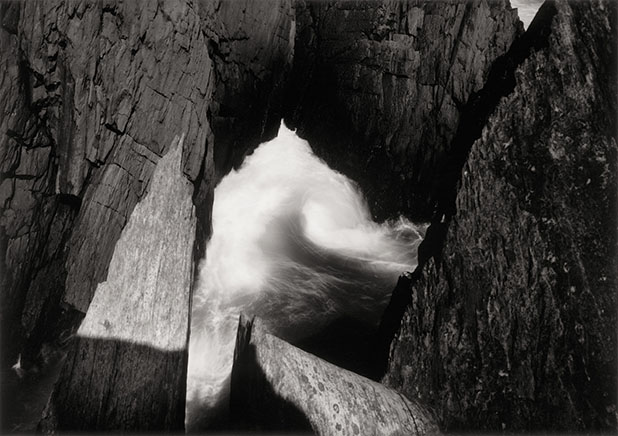

The one problem we might have with his images, though, is that most seem as isolated from a geographical or geological context as notations on Magellan’s nautical charts would have been. Cooper’s signature images are horizonless studies of white foam against black water. Even when there is a vertical rock face or distant horizon line to give us our bearings, the images are as abstract as an expressionist painting. Cooper acknowledges our inability to get our bearings with the images themselves by giving them titles of 50 words or more pinpointing the location of each and its significance. LACMA’s subtitle for the exhibition, “The World’s Edge,” edits Cooper’s original title for this body of work, which is “The World’s Edge – The Atlas of Emptiness and Extremism.”

This is a very large show – 130 works – considering how demanding the imagery is. In addition to the finished prints on the walls, there are six display cases placed throughout the exhibition, one with over 20 proof prints in it, and all of them on view to give us an insight into Cooper’s process. In the show’s last gallery, the last photograph in the exhibition is of “. . . the South-Most Point of the Isle of Nova Scotia, Canada.” The label also includes a text reading, “This is the point from which more than one thousand ships have been lost at sea, including those caught in the ‘Perfect Storm’ in 1991.” This puts into words a pall of grimness that hangs over the photographs, in the making of which Cooper’s 19th-century camera once went into the icy water followed by Cooper himself. Despite the mishaps annotated on its label, the last photograph in the show is hung next to a glass wall that, overlooking LACMA’s backyard, provides some relief.

In composition, the photograph mimics the piece that dominates the view outside, Michael Heiser’s “Levitated Mass,” the diorite granite and concrete boulder weighing 340 tons that, nonetheless, seems to be floating in space over a submerged walkway. In its own way, Heiser’s sculpture is as isolated from its natural context as Cooper’s compositions are from theirs. Govan had accompanied me to that last gallery, so I asked him whether he had placed that last Cooper image so it could have a conversation with Heiser’s piece. He wouldn’t take credit for that, but he did say he had ordered the view to the outside left open. It was a welcome relief after we’d spent so much time in the profound darkness of Cooper’s world.

A Premonitional Work—The North Atlantic Ocean, Cape Race, #2, the Isle of Newfoundland, Canada, 1998.

Goodyear’s essay concentrates on Cooper as a personality. She was attracted to him because he is such a compelling character. The only photograph of his in her New Yorker piece, though, is a double-page spread that serves as the title page with type laid over half of the image. Unlike his energetic personality, Cooper’s photographs are dark matter. They are beautiful, mysterious, but also, potentially, monotonous. On display in his tour of the LACMA show, as it is in Goodyear’s essay, Cooper’s ebullience is perhaps the ballast he needs to be able to photograph in such dark places.