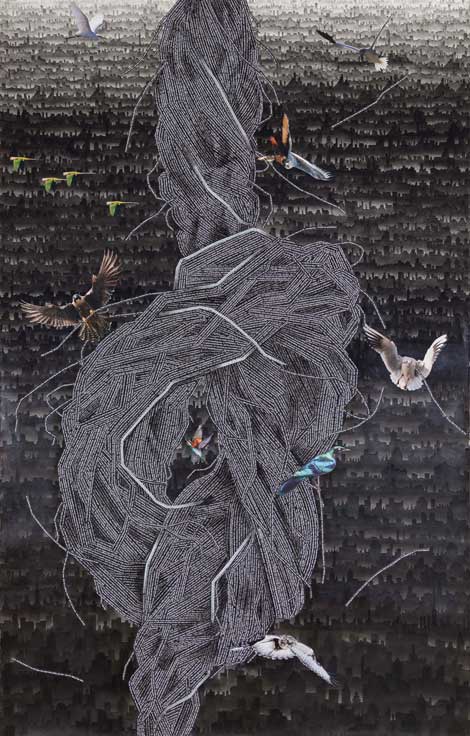

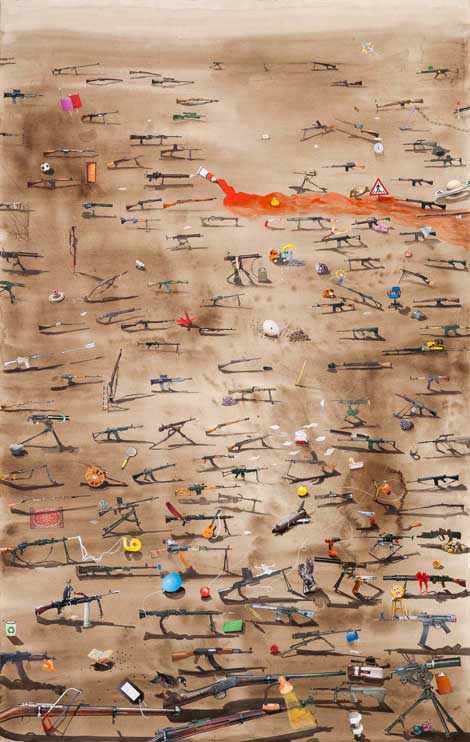

Artist Hema Upadhyay has been a force in Indian contemporary art for two decades. Still, her recent solo exhibition at Chemould Prescott Road in Mumbai in fall 2014 was a major event in both the artist’s trajectory and the landscape of Indian art today. “Fish in a Dead Landscape” was Upadhyay’s first solo exhibition in a decade at the gallery—one of Mumbai’s best—and incorporated the installations she has been creating since 2006 with a suite of new paintings combining appropriated digital imagery with paint, assemblage, text and personal narrative. The three-dimensional work is expansive and outward-looking, considering the geographies of poverty and wealth that continue to shape Mumbai’s astronomical growth. The paintings, some consisting of thousands of rice grains painted intermittently with English text, are introspective: informed by the pain of the artist’s recent high-profile divorce—involving a prolonged legal battle and salacious press. Upadhyay takes a more personal voice in this new body of work than she did in recent years, but her artistic impulse is ultimately a social one, connecting individual experience to a collective trauma of inequality and injustice.

Hema Upadhyay, installation view, image courtesy, Chemould Prescott Road and the artist, photo by Anil Rane.

Upadhyay is an artist who turns obsessiveness into a virtue. Whether filling a space from floor to ceiling with miniature fabrications of slum architectures, or covering a canvas end-to-end with individual grains of rice, her attention to detail is the counterpoint to a willful unruliness often present in her work. Text in Upadhyay’s paintings is at once essential and inscrutable, requiring patience (and magnification) to decipher, while producing a material line that can describe a wave, a knot or twigs held by birds under a bell jar. The exhibition’s title is a reference to fishermen working and living in shanties alongside the luminaries of Juhu Beach, an upscale area where the Upadhyays shared an apartment and some highly toxic interactions. Beauty is present alongside decay in this work.

Hema Upadhyay, installation view, image courtesy, Chemould Prescott Road and the artist, photo by Anil Rane.

This interest in an aesthetic of delight and horror places Upadhyay within the tradition of the sublime, an ideal state brought on by awe at the interplay between these oppositional forces. Yet the bombast associated with 19th-century German and English Romanticism is absent from her work. India is in some ways well served by Romanticism, both because this tradition is deeply informed by Hindu, Buddhist, and Sufi texts from the subcontinent, and because its weaving of grandiosity and empathy seems an apt form through which to articulate the overwhelming experience of modern life there.

Hema Upadhyay, installation view, image courtesy, Chemould Prescott Road and the artist, photo by Anil Rane.

Even so, Romantic traditions emerge from a colonizing framework that reinforces existing power structures as much as it champions individual liberation. Upadhyay turns this formula on its head, instead using personal catastrophe as a means of questioning the expectations of power. The sprawling mass of the city, from corrugated tin rooftops to the domes of mosques, unfolds opposite her personal anguish as a sharp rejoinder to any self-indulgence on the artist’s part. Instead, the work points toward the destructiveness that a society of haves and have-nots wreaks on both parties and on the Earth itself.