Monica Majoli, an artist and professor of art in painting and graduate studies at UC Irvine, whose work explores sexuality and intimacy, is interviewed by art historian, Ph.D. Candidate and Provost Fellow in the Humanities at USC, William J. Simmons.

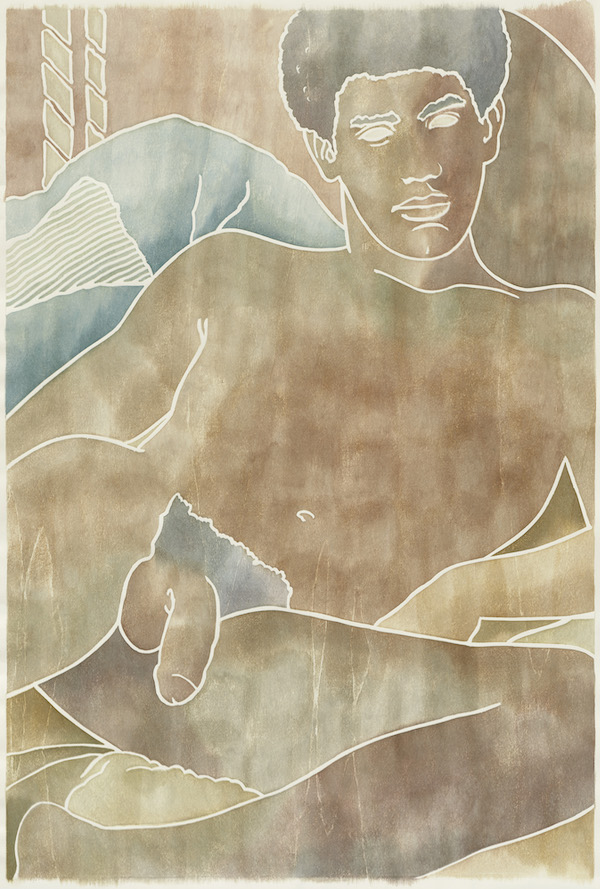

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Armando), 2019

WS: I’ve been really interested lately in queer nostalgia—a term that, I’ve found, some artists find grating. I do not mean nostalgia in a gay-men-who-love–Judy Garland way, or maybe I do. Point is, I’m wondering, what is your relationship to pastness, and to locating desire in the past? Where does appropriation (of emotion, perhaps) fit into your conception of pastness?

MM:

Judy Garland had been dead for 10 years, and I was about 12 when I became (romantically) obsessed with her after being given Judy at Carnegie Hall as a gift. My first concert was the female impersonator Jim Bailey in a small neighborhood theater in Beverly Hills. The audience in “Judy’s” thrall consisted of about ninety-eight gay men, my mom, and me. Jim as Judy was possibly the beginning of many surrogates that I came to identify as stand-ins for missing persons so loved and necessary that a stopgap was required to abate intolerable longing. By remaking time and reconfiguring by approximation, a third option opens–one that embodies love and fulfillment in its full complexity–one that accounts for loss and change and our lack of control over things needed and loved or of time itself.

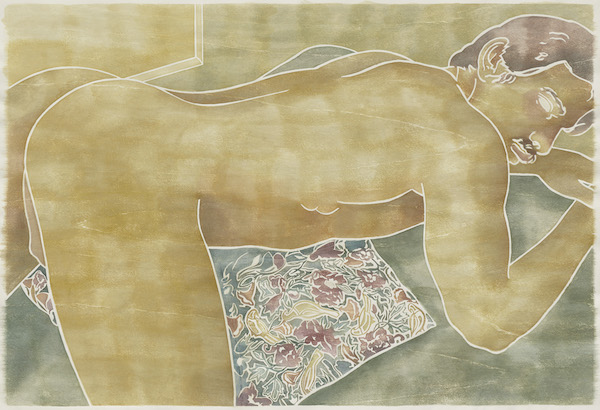

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Ted), 2019

Queer nostalgia haunts us. Why else would Over the Rainbow be a queer anthem from another time? It speaks of the yearning for the impossible–a location that embodies the unreachable. The thing about pastness is that one can revel in parts, not the whole, one can shape it with one’s will and through feeling and since it exists custom made it is therefore safe, private and again, curiously present though unreachable. The unreachable, in its permanence, can be a sustaining force.

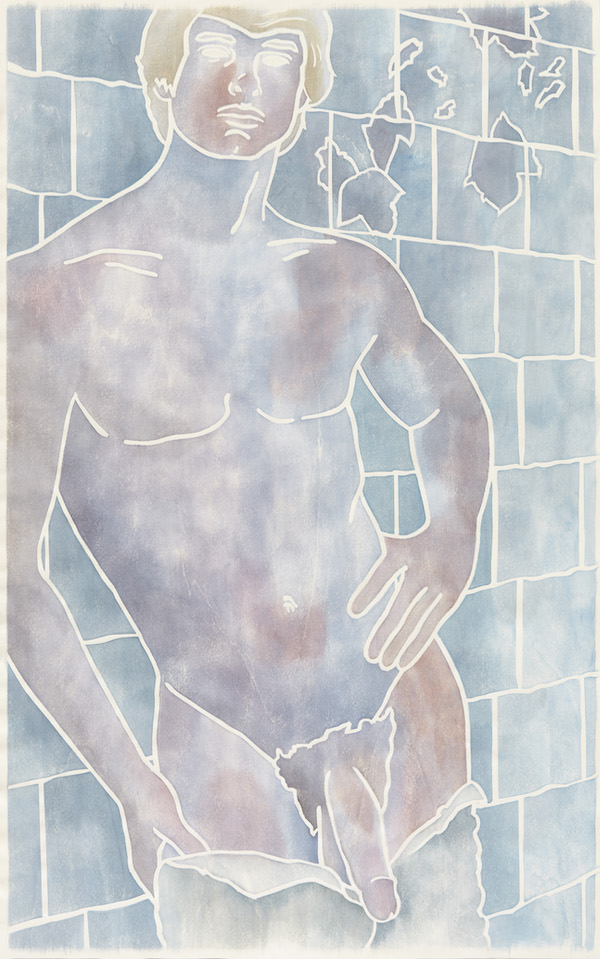

Pastness is linked to a memorializing instinct in my practice. AIDS figures into this as it defined the time when my friends and I came of age in the mid-’80s. I soon realized that as a lesbian, I was more a witness to a plague. The memorializing aspect of my painting practice became wedded to technique and method at that point, and I found meaning in that fusion. I began working slowly with sexually explicit, factual material in 1990. The elements of experience and recording held more urgency for me than fiction or pure material exploration with paint. It made the work real for me.

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Carl), 2019

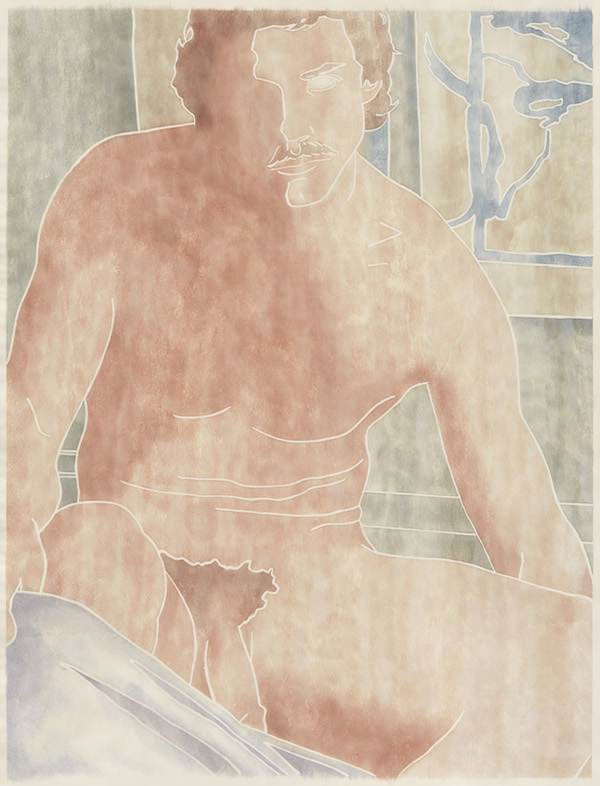

I was struck by the frequent use of the term “former lover” to describe the people in your “Black Mirror” series. It got me thinking about the degrees of intimacy inherent in your work that run the gamut from women who you’ve indeed loved and touched to men in porn magazines who you don’t really know. I wonder if any love or body is truly past, or, if you want to get really art-historical, if any medium can?

The act of painting a body over a long period, where a great deal of repetition is involved–whether belonging to a former lover or a man circa 1978 pictured in blueboy — leads to an internalization of the body/person I paint. So not only does the woman or man become animate, not past or absent, it enters my own lived experience over time. There’s a transmutation in painting that makes it possible to feel both identified and outside of my subject. Prolonged time and repetitive application–which has defined all my work– re-living and reconfiguring the other as self is not sought after as much as happens. I agree that I don’t experience my subjects as past or various periods of art history or the medium of painting generally as belonging to the past. Being affected and changed by someone or something makes that thing alive, present, and essential. I think the ways that artists are inspired by artists from other eras, the way a body of work can be responsive to a “conversation” with an artist long dead–is evidence of the inaccuracy of these particular categories. Painting is a temporal medium and exists in simultaneous time–the time it was made, the time of making that one imagines when looking at it, and the time at the moment. The collapse of linear time is one metaphysical aspect of the medium.

Monica Majoli, Blueboy (Ryan), 2016

How does care, specifically the care you have taken with Lutz Bacher’s work after her passing, relate to your own work?

My exposure to Lutz’ practice, directly in studio visits over decades and many conversations with her, make the boundaries between my own work and hers somewhat hard to define. In installing one of the first posthumous exhibitions of her work with “Blue Wave” at UCI, I felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of doing justice to her work. I was also afraid that the work would not feel like her and would, therefore, reinforce her absence, her death. None of the works had been installed previously, so little determined the venture but her guiding ideas and studio experiments. Without Lutz to validate my decisions, I relied on a sense of recognition of her during the process. What you’re describing when you refer to care is our relationship. And collaboration, which is another form of making care in relation. Boundaries become much more complicated after death.

In general, my work is about attachment. It’s private to the point of being too intimate for public space. The relationship between myself and the one looking enacts a triangulation that fuels my engagement in the process. I’m aware of an outward direction toward the spectator and an inward direction toward the subject. I work between these two points of awareness or contact.