William Blake embodies a wild paradox in Western cultural history. The only great poet who was also a gifted painter, Blake was a barely educated autodidact whose ideas anticipated Freud, Marx and Einstein. Never published in his lifetime, The Tyger (1795) is now the most frequently taught lyric poem in American and British high schools and universities. His lifetime (1757–1827) dates him with the English Romantics, yet he had little or no connection with the “Romantic ” movement or with any movement at all except that of the mythological figures he saw so clearly in his mind.

The current show at the Getty respects this paradox by embracing his dual identity as poet and painter, which is appropriate, since the goal of all Blake’s creative work is nothing less than the transformation of the reader/viewer’s relationship to reality. Two key Blake aphorisms indicate what’s at stake: “If the Doors of Perception were cleansed, everything would be seen as it is, Infinite” is one, and “How do you know but that every bird that cuts the airy way is an immense world of delight, close’d by your senses five?” is the other. Blake’s poetry and art both aspire to a shared result: the cleansing of fear and the opening of the mind to love. His personal mythology, with character names such as Urizen, Orc, Enitharmon and Oothoon, was the way Blake dramatized the possibility of this transformation and the life it could provide.

William Blake, The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, c. 1826. Tate, London. Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson, 1949. Photo © Tate. Courtesy of the Getty Museum

Organizers Edina Adam and Julian Brooks have ambitiously aimed at a full picture of Blake as a professional printmaker, painter-illustrator (mostly in watercolor or tempera, mostly of Bible scenes), and poet-prophet of the illustrated (or “illuminated”) books, the center of his work. Among these is a rarity: all 18 plates of his “illuminated” poem America: A Prophecy, made in 1793. Muscular figures with punk rock hair leap out of flames as the poet intones, “On my American plains I feel the struggling afflictions / Endur’d by roots that writhe their arms into the nether deep … ” True then, true now.

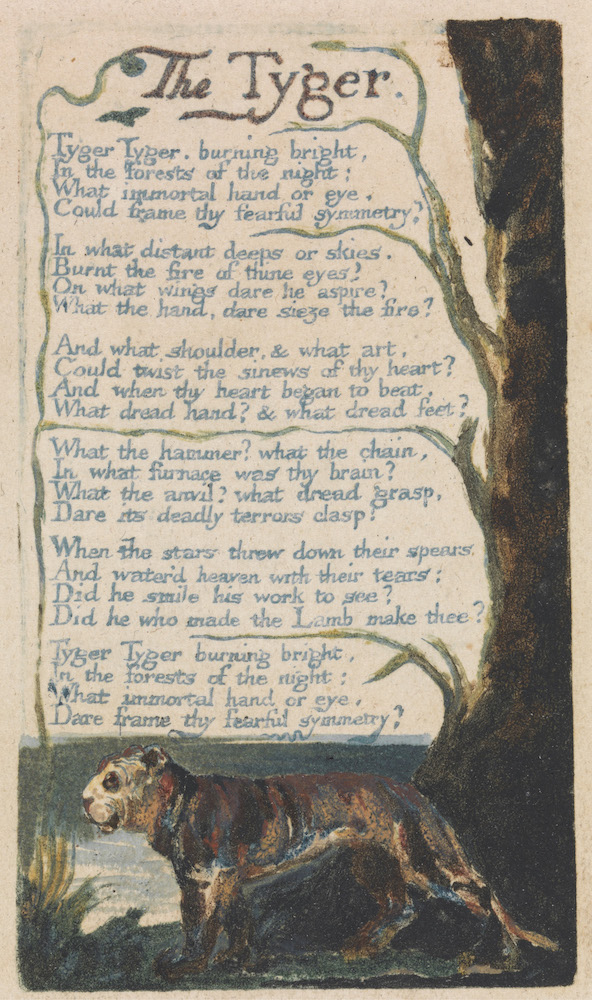

Of course, a handprinted, hand-colored version of The Tyger, along with other plates from Songs of Innocence and Experience (1795), are on display. As with seeing Dalí’s 1931 Persistence of Memory, one is struck by the smallness of these plates, as balanced against their size in the culture. The Tyger is a little bigger than a baseball card. The museum supplies magnifying glasses, and when one examines the “illumination,” the secret of the poem is revealed: The tiger is calm and alert and nothing in the scene is on fire. There is no danger anywhere except in the speaker’s mind. The poem is a warning about paranoia.

After a couple of hours absorbing “William Blake: Visionary,” I stepped out onto the Getty terrace. It was a clear November day. Sometimes, the view the Getty gives of the city competes with the art on the walls. Sometimes the view even wins. But sometimes, the view becomes a complement to the art, even an illustration of its guiding spirit. That’s what happened to me with the Blake show: The city itself, and the sea and sky beyond it, appeared as a 3D example of the boundary-defying genius on display indoors. LA looked infinite.

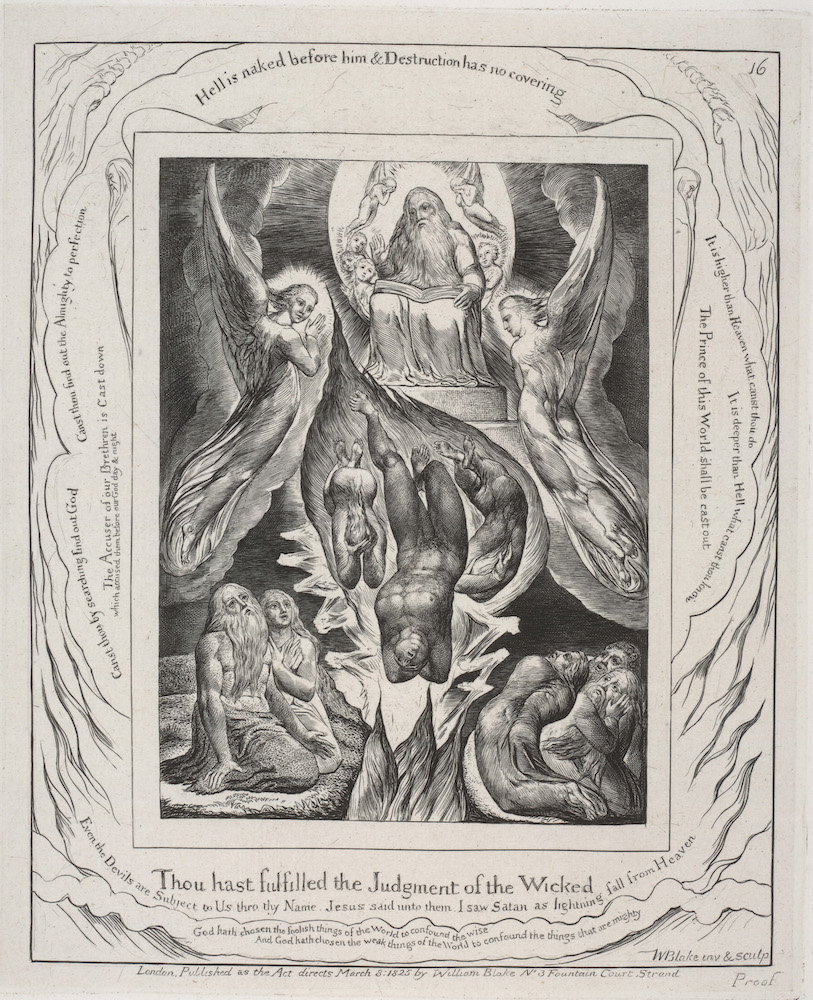

William Blake, Plate 16 from llustrations from the Book of Job, printed 1825. The Huntington Library Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino. From the Edward W. and Julia B. Bodman Collection. Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Terrific description of the merging of Blake and view. I remember first seeing his work at the Frick and was amazed way back then. Thanks for the article!

This is the best Blake show overall that I have seen since 1970 (Tate)…