This Thursday we had the pleasure of attending the press preview and breakfast at Fort Gansevoort’s new Los Angeles space featuring Christopher Myers’ inaugural show, Drapetomania.

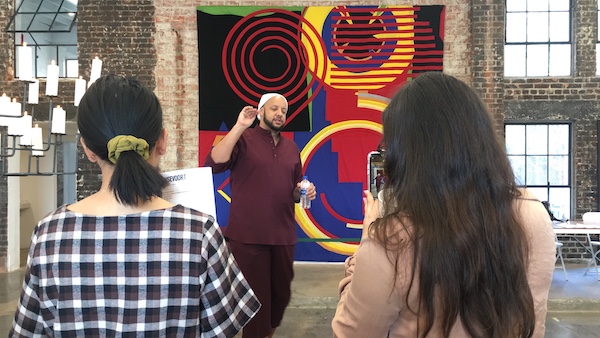

Christopher Myers at his artist talk at Fort Gansevoort Los Angeles.

Fort Gansevoort’s founders, Adam Shopkorn and Carolyn Tate Angel, hosted the event during which the enigmatic artist captivated the audience as he guided us through the exhibition—no surprise due to his background in theatre. The artists’ talk began gathered outside the gallery’s new space of the Merrick Building in East Hollywood. Enjoying the sunny morning, we then made our way through the building, which featured gorgeous high ceilings, Art Deco details and expansive walls—all beautifully showcasing the monumental textile and sculptural works of Myers.

Installation view of Drapetomania at Fort Gansevoort Los Angeles.

The show incorporated sculptural works and three-dozen new textile pieces, which were hand-stitched in central Egypt by fabric workers. Myers reasoned that in a way, each served as its own flag for specific groups of people. The resulting imagery contained both personal and global mythology and portrayed stories of civil rights, contemporary activism, black identity and notions of freedom versus bondage. Myers explained that his inspiration lived in the ever-present question of, “What are you running away from and what are you running to?” This concept truly summarized the exhibition and its title, Drapetomania, which in 1851, was a fabricated mental illness hypothesized by American physician Samuel A. Cartwright as the cause of African American slaves fleeing captivity.

A viewer with Christopher Myers’ work at Fort Gansevoort Los Angeles.

Through his concepts behind process and craft, Myers seamlessly weaves visuals depicting the magical and remarkable, while also referencing the everyday. One sculptural work, “Shackle and Light,” struck me in particular. Positioned in the center of the space, the massive collar made from steel, candles, and flame was placed around a mannequin’s neck. The restrictive collar branched out in various directions and at the end of each rod stood a candle, forcing distance between viewer and the fabricated concept of another body. Myers explained this scripted length of separation isolated the subject of the work—illuminating the social death of slavery.

Christopher Myers at his artist talk at Fort Gansevoort Los Angeles.

Each of Myers’ work brilliantly served as objects of performance and in this way humanized wounded and segregated bodies easily seen as objects. In the presence of the exhibition, the conversation was opened of how to re-contextualize and liberate these once bonded ideas. Myers concluded his talk with the sentiment, “The only language I speak really well is making—and that’s what this is all about.” As we left the talk, we couldn’t agree more.