The art world as we know it is in a constant state of reinvention and definition, continually seeking relevance. In this quarter of the great game, the self-intentioned academics are running with the ball. Global societal, biological and environmental issues are king and Art is the lowly jester. A fad in galleries and biennials around the world, this current curatorial trend has dominated the Honolulu Biennial.

With over 93,000 visitors, 9 venues and 270 works from 33 artists of 19 nations, the inaugural Honolulu Biennial has successfully folded its tent after a 61-day exhibition. Without a sigh of relief, plans for the second are already in progress. Surrounded by leagues of water and far from convenience, Honolulu may seem an unlikely destination for a biennial. Yet there is no greater place than the heart of the wide Pacific Rim for a confluence of continents, cultures and art.

Art is many things and it is everything. It can be political. It can celebrate or denigrate. It can inform or subvert. As a witness, Francisco Goya produced his “Disasters of War.” The Dadaists created a whole new language and style of art to discuss and illuminate the horrors of their times. Today, issues are pondered from the objectivity of a comfy couch and an iPhone screen—and so is outrage. There is strength in numbers. We can all agree that genocide, pollution and bullies are bad. With the depth of a selfie, Issue Art becomes nothing more than self-serving.

The very contemporary curatorial choices in this biennial reflect two different approaches to art and life. One comes from a traditional celebration of art making, study and invention. The other, defensive, worrisome and often angry, seeks to use fine art as a flaming spear to lament, not solve, the many injustices of our world. If it hadn’t been for a gigantic Mylar flying pig at the exit, I would have purposefully run into oncoming traffic.

Subtlety is a skill, as divine as a steady hand on a pinstripe brush. Unfortunately, many of these issue-laden pieces land with the delicacy of a leiomano, the Hawaiian war club ribbed with sharks teeth. Fumio Nanjo serves as the curatorial director of this biennial. In his day job, he is the busy and much sought after director of the cutting edge Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. The steely focus of the Mori, international in scope, is the artist and their creation. Ngahiraka Mason, the curator with two feet on the ground, curates this biennial. Before her recent move to Hawaii, Mason served as the Indigenous Curator of Maori Art, for the Auckland Art Gallery, for 21 years.

Yayoi Kusama

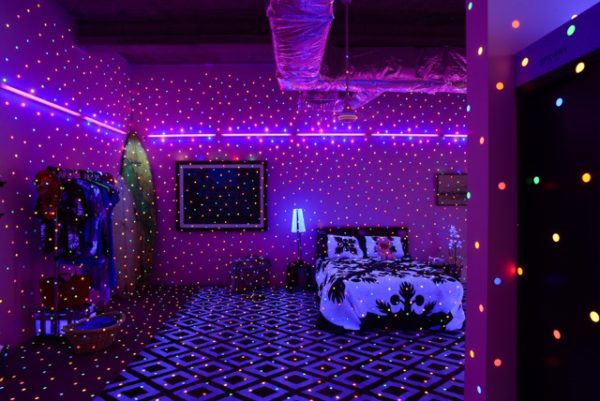

I had only seen the work of Yayoi Kusama in books, magazines and at a distance. “Ubiquitous,” I imprudently murmured. The Honolulu Biennial gave me my first contact. I immediately ate my words and fell madly in love, with deep appreciation. Her Infinity Room at the Howard Hughes headquarters is jaw dropping and immersive. The black-lit living room was dressed with evocative Hawaiiana and locally found objects. Everything had been dazzled with bright neon polka dots. Clearly, her second effort in the show, located at the Foster Botanical Garden, had not been installed; I believe the 15 pieces must have bloomed from the soil. Her large pink polka dotted sculptures, organic abstracts, were so perfectly situated, I assumed the 164-year-old garden had been designed around them. Fun Fact: Just a dozen yards away, on December 7, 1941, an anti-aircraft shell missed and blew up a children’s Japanese language school. The incredible Foster Botanical Garden is one of nine brilliant sites in the biennial. As Honolulu mayor Kirk Caldwell said at the Honolulu Biennial opening, “The garden is a work of art unto itself.”

Charlton Hupa’a Hee is a quiet and thoughtful artist, a seeker. I have attended several of his talks. Hee is learning much about his place in the world as an artist on an isolated island and as a Hawaiian. Under the interlocking canopies of a Cinnamon and an Ebony tree, the sculptor has arranged a decorated series of hanging and resting ceramic gourds. If you choose to disregard the beauty of the works, you may note his playful discourse between art, nature and progress. More of Hee’s work can be found at the stately and important Bishop Museum, another venue in the biennial. This is an artist to watch and support. He is a lifer.

Sean Connelly

We need to get Hawaii hero Sean Connelly into a City Council meeting. The architect and urban planner, with a set of very impressive sheepskins, has a brilliant and comprehensive master plan to restore the Honolulu ahupua’a. He and his many supporters are certain that they can clean up the rainwater rivers and restore nature’s balance without having to scrap a single skyscraper. To advocate thatching as a sustainable building material, I would think a construction convention would have a greater impact. Connelly has a sculpture in the show, outdoors at the Foster Botanical Garden. Unfortunately, there is not a gallery wall of text to explain the motivations of the exhibit, which loses comprehension alone in the arbor. One cannot discount Connelly, just his method.

Brooke Mahnken and Oriana Fettuccine

Conversely, next door on the same green is a sweet sculpture by Lynne Yamamoto of Hawaii. She has created a nostalgic and effective work for the homes and neighborhoods that stood in the same area in the not so distant past. The dollhouse-like work, approximately 4 by 4 by 9 feet, happens to face a freeway that destroyed such communities. Like a relaxed sigh for better days, the work invites you to sit inside. The experience is quite calming, familial and a little bit sad.

Another spectacular venue in the biennial is the headquarters of the Howard Hughes Corporation, the generous and brave founding sponsor. The developer rescued and restored the 1962 modernist masterpiece by local architect Vladimir Ossipoff. The venue displays the work of three artists. Kusama has her Infinity Room. Choi Jeong Hwa of Korea makes us smile and soar with a gigantic breathing, flowing lotus flower. The program note curbed my enthusiasm and soul sailing with self-righteous misery, “The work inspires one to create and maintain an identity within a globalizing society.” Now I am inspired to bash my skull against a stainless steel rock.

Zhan Wang

Speaking of stainless steel rocks, Zhan Wang of China displays his greatest work in the biennial at the Hughes HQ. (A lesser piece can be found in front of the Honolulu Museum of Art, their only fingerprint in this upstart biennial.) Wang recreates a boulder, in exacting detail, in stainless steel. His work is only as impressive as nature intended. His Artificial Rock No. 131 inspires wonder. The original must have been eroded by time and water into a complex and otherworldly shape. The mysterious piece is a triumph of the artist’s skill and the magnificence of our anonymous creator.

Choi Jeong Hwa

At the Hub, a series of sculptures, unlisted in program notes, have been hidden, only to be viewed, from the outside and around a corner. The works are easily identifiable and fun. They are gigantic versions of informal jewelry. Like Puka Shell or groovy beaded necklaces. Or bracelets made of hard, colorful candy. The artist, Choi Jeong Hwa, used similar materials that he applied to his towering work at the Honolulu Hale. The sculpture was installed in the interior three-story courtyard of the 1928 government building, a Spanish Italian Colonial Revival mash-up. The work presents a series of 10 towers, each made of round objects, diminishing in size as they leap to the skylight. Five towers are black, alternating with five made of many colors. The hues are rough and faded. Some of these odd gigantic “beads” have handles. By design and in that location, Choi’s work is impressive. One is encouraged to stand inside and experience his marvel. I’d award Choi a blue ribbon that reads, “Best in Show.” More fun can be had to learn that the sculptures were inspired by found materials. His gigantic beads are in truth plastic marine buoys of many shapes and colors that have crossed many seas to litter the shores of Hawai’i. Greater meaning is a wonderful thing when it is discovered, rather than imposed upon us. Subtle Choi does not need a leiomano.

Alexander Lee

The heartbeat of the Honolulu Biennial is called the Hub. The talented organizers have made a spectacular effort in creating a comfortably generous and stylish museum of 60,000 square feet. The installations and exhibits were designed with care. A beautiful and spacious octagonal set, angled to the compass, was built to showcase the sculpture of New Zealand’s Brett Graham. His monochromatic work belies the rich colors of Kaho’olawe, the lost Hawaiian island that was depopulated for military target practice. For Tahiti-raised Alexander Lee, the biennial organizers have created a Hollywood extravaganza in 4D to celebrate his elegant horror of the atomic testing in French Polynesia. Black walls and a vitrine were not painted, but burned black. The smell elevates the terror.

Marques Hanalei Marzan Performance

There are many rooms in our House of Culture. Like a knife to a gunfight, I would have hesitated to bring couture to a biennial. Every medium has a place. Much acreage and a large wall were devoted to the work of local star Marques Hanalei Marzan. Every square inch was worth it. Quite simply, impeccably and appropriately, he honored and dressed four of the greatest Hawaiian Gods. His fashion procession at the opening was a performance.

One of the outstanding works in the biennial is a video by Iraq-born Sama Alshaibi. The magical film takes us to foreign landscapes and other worlds of contrasting colors and great beauty. The people are unfamiliar, yet very much like us, as they silently commingle, together and alone with nature. With simple camera devices, the artist creates a sense of quiet wonder. All is right in this worl…—Sorry. Stop. I’m wrong. The film is about our planet’s diminishing supply of potable water. Funny, I didn’t see that in the video.

Greg Semu

Greg Semu

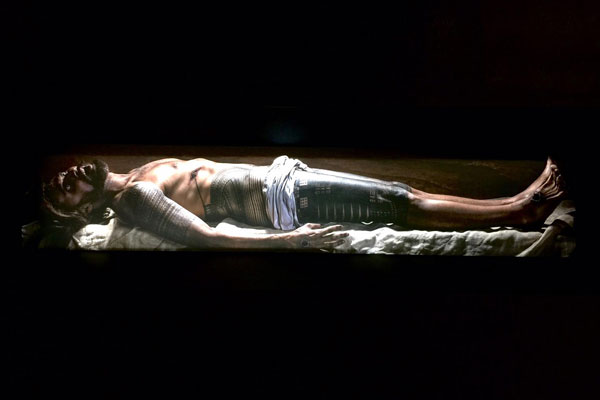

Western Art is our go-to standard; it’s the loudest one we’ve got and an uneasy dance partner for many. A wall note for the work of show favorite Greg Semu reads, “Further de-westernizing famous paintings, Semu …” How do you de-westernize Western paintings? I don’t think that’s what the New Zealand-born Samoan was intending. Two standout works in the show use the gravity of famous paintings to deliver an indigenous experience and history. Three photographs from a larger body of work document the progress of his Samoan Tatau markings. The ingenious presentation of his “After Hans Holbein the Younger—The Body of Dead Christ” is a testament to the biennial organizers and their commitment to the artist’s intentions and the viewer’s experience. Damnably, upon the artist’s request, a valuable large wall was wasted with an empty step and repeat pattern of a few pages from Semu’s journal. This beholder was left wanting more. Greg Semu is a force of his nature.

Drew Broderick

I am not the only one to think that local artist Drew Broderick has a great and shining potential. His effort for the biennial was given the most prominent space in the exhibition. Familiar with his work, I believe the young artist is capable of great wit and showmanship. Sadly, his arrow missed an easy bullseye. I’d be happy to break it down, but I rather hope the artist will reengage with the work and present the potentially prominent piece in another future. A thoroughbred trots or flies by temperament.

TeamLab

In Hawaii, there is no art show without a segment for the keiki, the kids. I dunno why. Relevance? The high price of babysitters? Fumio Nanjo took care of that with style and aplomb. TeamLab from Japan offered an interactive jungle where viewers could watch their drawings of flora and fauna come to life and scamper across an otherworld. It was fun to watch the adults elbow the kids away to cut in line.

The overwhelming majority of wall text, identification and descriptions of the artist and the work, referenced a global environmental or human catastrophe. Do these artists need this value? Does it make their inclusion more relevant and worthy of our attention? What’s on stage here?

Lee Ming Wei

Gasping for air and drowning in our global miseries, I greatly appreciated the sweet sincerity of artist Lee Mingwei of Taiwan. His photographs with words honored the passing of his grandmother. He planted a lily bulb and coddled the flower through the 100 days of its living and dying. Gentle grief and good passings.

In two years time, I am eager to see what the second Honolulu Biennial will bring. A new crew of curators will see this world with a fresh set of eyes. As fast as our culture is now spinning, the second incursion will be a feast beyond our current comprehension.

The great and wide Pacific Rim offers many mysteries to be discovered, exotic wonders to appreciate and great beauties to behold. The gnashing tectonic plates of the volatile Ring of Fire are edged with extremely diverse cultures, histories and lifestyles. The Honolulu Biennial stands in the heart, the hub, the middle of it all.

After five years of hoping and planning, the Honolulu Biennial has now been established. There will be a second and a third and a future. The highly professional and experienced founders, Isabella Ellaheh Hughes, K. J. Baysa and Katherine Leilani Tuider have turned their sandy notion into a solid footprint.

Hawaii is wary and not quick to embrace the new and untested. Kudos to the Howard Hughes Corporation and all the sponsors for their arts activism. There can be no future of art in Hawai’i without them.

Say Aloha to the world’s newest Biennial!

__________________________________________________

GORDY GRUNDY is a Pacific-based artist and arts writer. His visual and literary works can be found at www.GordyGrundy.com