For all the talk about its fragility (at least in economic terms), opera remains a remarkably durable art form. Great music wedded to a strong dramatic core can never be easily dismissed. Add some good orchestration and the human voice in its full dynamic range, and—as some theatrically minded people figured out somewhere between the late Middle Ages and the Baroque—you just might have something. Great opera survives for the simple reason that it’s capable of surviving just about any theatrical assault.

It was only natural that Barrie Kosky be invited back after the surprise smash success of his silent screen comedy/live action animation-inspired Zauberflöte last year. But the silver screen (to say nothing of black-and-white) only takes us so far, especially in the theatre. The current Los Angeles Opera production of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas is not exactly black-and-white. The airy, floral and vegetal pastel color scheme, at least in terms of costuming (the backdrop is more or less monochromatic), is charming—loosely 18th century, with hints of a 20th century update.

Maybe a little too airy—and yet somehow airless. Dido’s ascent from the court masque is fairly transparent here (the Sorceress and her two hench-wenches personify the layer of allegory embroidered into the libretto along the lines of Spenser’s Faerie Queen). But Purcell’s score is far removed from the stuff of court festival, still less the domain of coy or camp. Dido is all about gravitas; the character of Dido herself about a fatalism as dark as Carthage’s fate. Paula Murrihy has a fine, clarion voice, but the shadings are a bit pallid. We should sense the approaching twilight even as she’s entertaining some dubious foreplay with her Trojan hero (there is nothing entirely unshadowed in this opera)—and we don’t.

Belinda (Kateryna Kasper) and the second handmaiden (Summer Hassan) are the blithe optimists here—blown in any direction by the capriciousness of the gods (or their designated trouble-makers). Kosky underscores this with a see-sawing movement of court and chorus across the stage—like an hour-glass turned and on its side and tipped back and forth with the sands shifting from one side to the other. But they don’t need to be turned into tittering schoolgirls. Their weak grasp on statecraft is a given. The modulations between relative major and minor keys alone give us a harmonic read on this listing ship of state.

Onto this floating spar steps … Mr. Rogers—or at least that’s the way Liam Bonner’s costuming ‘read’ from somewhere between the middle and back rows of the orchestra. The Los Angeles Times’ Mark Swed described it as more of a lounge singer look (a casual “Dean Martin”); and close-ups disclose details that revise this impression somewhat. But “Dino” at his most laid-back golf-course casual would have had more impact than this Aeneas. This is not to slight Bonner, who was fine. But locked down and flattened out with the rest of the cast and chorus, there’s not a lot of room to ‘confess the flame’ or ‘pursue [his] conquest.’ He might as well shove off.

Opera abhors a vacuum, though; and the Sorceress (John Holiday—superb) and his two witches (G. Thomas Allen and Darryl Taylor—both excellent), nimbly chew up the spare scenery and all but steal the show. Kosky certainly recognized the limits he had pushed himself up against; and tried to compensate by pushing the players into the orchestra pit and some of the orchestra soloists into the off-stage ‘grove.’ The orchestra and chorus shine; but even insisting upon the box-pleat backdrop, a thrust stage might have helped articulate the balance of the action. As it is, he leaves Dido on stage alone for her final lament—faintly ridiculous, depleted of gravitas, even pathos. As chorus and orchestra exited one by one (à la Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony), Dido was left coughing her way to oblivion. We didn’t know if we were waiting for the curtain or an IV-drip.

In the popular conception of the misbegotten marriage or romance, the woman’s lament always trumps the man’s. ‘I married a witch,’ the guy complains; and the girl comes back with ‘I married a murderer.’ Or (in the art world?) a collector. Or someone with a few skeletons rattling away in the closet(s). Really any functional psychotic will do.

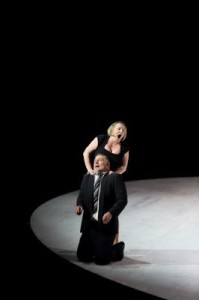

This is not always easy to put across to a post-modern audience and I commend Kosky for really going out of (or maybe into) the box to put another spin (literally) on Bela Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle. Once again, he’s flattened out the staging—here reduced to a slowly rotating and pivoting disc and a starkly black-and-white scheme. This actually works to some (180?) degree for the characters—properly black-suited Bluebeard (Robert Hayward) and Judith (Claudia Mahnke) in her perfect black sheath dress; not so much for the production as a whole. In Kosky’s scheme, they’re the quintessential 20th century neurotic lovers once satirized so brilliantly by Jules Feiffer. The opera seems to almost play out panel by panel as the couple cling, hug and tug, huddle and tussle, hover and torment one another, and Judith manages to shake open one chamber after another.

But to return to those rooms, closets, chambers (one of them actually turns out to be a dungeon or torture chamber; even the ‘garden’ is ‘bloody’)—we were advised before the performance that we should forget about any actual doors or notional rooms in the libretto. Kosky’s glib comment was that “It’s not about architecture.” But it is. It’s a musical and theatrical architecture comparable to a suite of rooms, each opening upon the next, with its own reveal and altered perspective. More important to the musical sense of the score is the lighting. Even if the rooms are treated as mere abstractions, the reveal and light, color, tonality behind each door are crucial to the opera’s dramatic and harmonic sense. The score is all about chromaticism and harmonic/dramatic shifts and contrast. (Even the Opera’s own program notes took note of the color cues and the dissonant minor second [G# and A—in the horns, flutes and oboes] sometimes referred to as a ‘blood motif.’) Instead of lighting cues, Kosky substituted in a props and effects with limited success. It must be said that that Mahnke and Hayward made the most of them—and the entire stage—under the bleached out lighting. (A trio of couples, suggesting their ‘shadow lives/selves’ seemed more awkward than illuminating, merely complicating the choreography.) Mahnke blazed gorgeously through it all.

Kosky is not lacking in scenographic sense: Mahnke and Hayward were brilliantly directed/choreographed through these ‘panels.’ Whether it served Bartok’s score effectively is another issue. The opera demands more than just a slide/transparency ‘carousel’ or a pantomime, however diverting. And even Jules Feiffer has used color—increasingly in recent work. Both of these operas are extended lamentations on our characters and fates. But they’re trying to take us somewhere—even if that place is a blood-soaked garden or the scorched earth. (We can be ‘held’ by the music alone.) In the meantime (memo to the Los Angeles Opera), if you’re looking for Feiffer—get Feiffer!