The entrance to Hiroshi Sugimoto’s exhibition at Lisson Gallery, “Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form” is partially blocked by a curved wooden wall. The wall commands recognition, separating the exhibition from the outside world. It immediately invites the visitor to become a conscious, active participant, as if asking us to wait behind the scenes for our cue to enter center stage. At the very least, the entrance articulates a request for commitment on the part of the viewer and establishes certain visual rules and sensorial dynamics. Beyond active participation, the massive installation indicates that the space will defy our expectations.

The show marks the return of the renowned conceptual photographer, artist, and architect to Los Angeles for the first time in over a decade. Sugimoto, who was born in Tokyo and graduated from LA’s Art Center College of Design in 1972, uses cameras and photographic processes to explore time, light, and the relationships between truth, fiction, and vision. In past bodies of work spanning a decades-long career, Sugimoto documented dioramas at New York’s American Museum of Natural History and movie theaters across the country; he presented wax figures isolated from their museum context in ethereal, dramatic portraits; he captured bursts of electrical energy on dry plates in his darkroom; and he photographed horizon lines worldwide, framing cloudless skies and sharp lines as an origin point for his own consciousness. The

artist’s in-depth investigations of visual perception, natural elements and photographic properties articulate a concern with collective and personal histories and the markings of time, as well as the limitations and possibilities of human perception.

Exhibition view of Optical Allusion at Lisson Gallery Los Angeles, 15 November–January 2025. © Hiroshi Sugimoto, Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

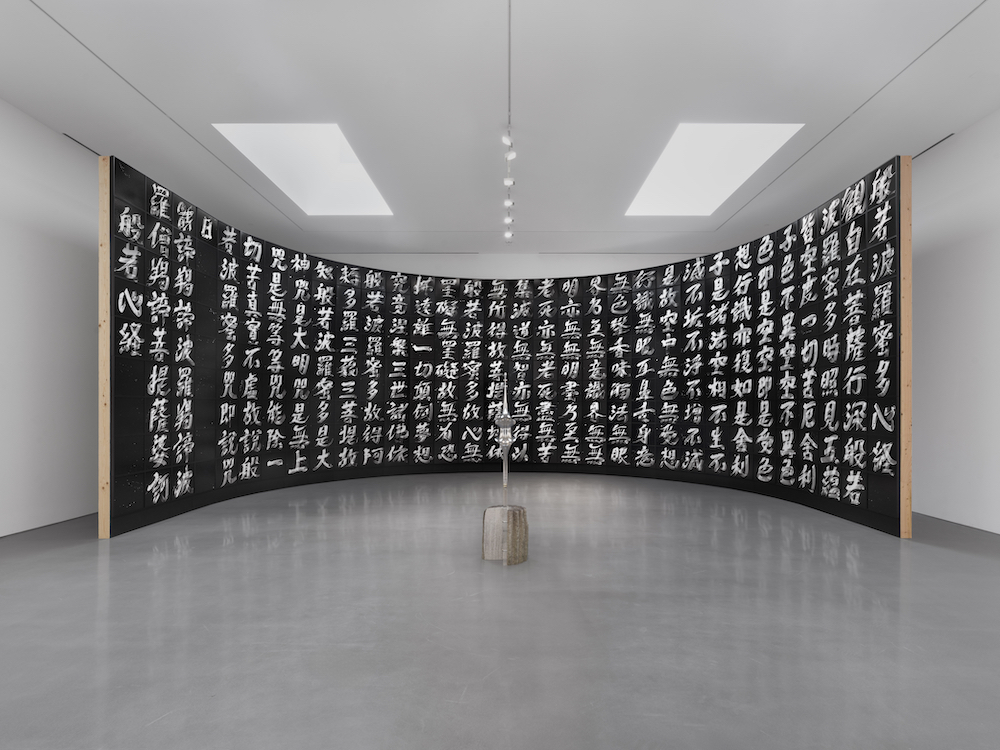

Past the verso of the curved wall, viewers find themselves immersed in the meditative Brush Impressions, Heart Sutra (2023)—288 gelatin silver prints, each of which measures 19.5 x 23.5 inches and presents a Kanji character (Japanese writing that uses Chinese characters). Together, they depict the Heart Sutra, a key scripture in East Asian Buddhism. Considered the most frequently recited text in Mahayana Buddhism, it discusses the fundamental emptiness of all phenomena and the transience of forms and objects. The title of the show is a direct quote from the Sutra, unveiling Sugimoto’s own preoccupation with challenging traditional notions of disciplinary, conceptual, and sensorial boundaries. To produce the calligraphic prints, Sugimoto used a fixer as his painting material, applied to expired photo paper. When he turns on the lights in the darkroom, the color of the surface is fixed in black, while the calligraphy remains white. The resulting image is a camera-less work that speaks to the bare elements of photography.

Directly in front of the wall hovers Kuen’s Surface (2024), a slender, delicate sculpture made of stainless steel and acrylic. Sugimoto developed the sculpture’s form out of a mathematical equation that describes a surface with a constant negative curvature. This abstracted form seems to float a few inches above a curved block of stone (Sugimoto found the stone, a Chinese tool originally hitched to a donkey and used for farming). The sculpture elegantly engages with geometric ideas through handcrafted physical forms.

Across from them are six images of Buddhas: groupings of sculptures found at a Kyoto shrine that has about one thousand figurines. The artist photographed the sculptures at dawn, and they appear to emerge from the dark. Sugimoto’s work exists at those meeting points—between darkness and light, horizons and skies, negative and positive, the possibility of emptiness and the inescapable presence of form—posing an infinite question rather than a finite response.