I was generally sympathetic to the examination of remote machinic vision on display at XPO Gallery, with their presentation of a Brooklyn-heavy group show that is weirdly shut to the public: HIKE, HACK, HIC et NUNC. Interestingly, it coincided with the punch of learning that a Russia-based website now offers the world peeks into private homes and businesses around the world via live feeds from web-cam baby monitors and security cameras.

Curated by Alexis Jakubowicz and Jean-Brice Moutout, it is a show intended to be seen virtually on a screen by the world online, and/or in actuality when accessed privately by appointment only. This mixing of the two experiences is what gives the show its merit and viractual impact, saving it from mere camp theatrics. It draws us into the question of how technical apparatus shapes what can be perceived and conceived by constructing an intertwining pretend (fairy-like) space, ideal for floating between modes of knowing.

It would be unproblematic to criticize the exhibition’s technological incompetence when compared to earlier telematic masters like Wolfgang Staehle, Paul Sermon and Ken Goldberg (or the recent political exactitude of !Mediengruppe Bitnik, artists who use distant hacking as an artistic strategy) – as the web-cameras used in the show (that make for the broad intellectual point of remote perspective) amusingly do not work. In that way it is an elaborate mannerist farce.

The online component that feigns live web-cam feeds is actually a combination of non-streaming gif animations and vimeo-hosted videos. I encountered in the show a rather tawdry (simulations of simulations of simulations) techno Arte Povera post-internet version of the high-tech aesthetics of technoromanticism. Regardless of said tawdriness, the encounter still managed to shift my attention from the realism of the object to the realism of the means of production of perception. Thus, though somewhat lost in transmition, it still participates in the examination of the net as the major ideology of our age, whether one approves of its diffusion or condemns and struggles against it.

It is a fun collection of art that configures a pluralist understanding of our networked world by refusing to treat machinic vision as an ontology. Rather, it insists on machinic vision’s constructivist and provisional make-up, thus serving again the poetic function for art that began with the displacement techniques of the early Surrealists.

A fairyland feeling is established throughout the gallery by Madrid artist Manuel Fernandez’s short video soundtrack of “Provisional Landscape” (2013), generated from audiovisual stock material. It provides a pixie-like audio reverberation that embraces the space.

Guillaume Collignon’s work provides a key to the telematic-landscape theme, while also hinting at the meaty world of now (nunc in French). Nowhere is this more apparent (even as it too was not working) than in Jill Magid’s alluring “Legoland” (2000) video, as it was cheekily hidden behind a black velvet curtain. As seen on the online show, it is a rather sexy video the artist made with an infrared security camera mounted on her shoe, shooting between her apparently pantiless legs at night amongst tall buildings, that include, I think, the World Trade Towers. At 28 seconds in, there is a pivotal moment where a sliver of gleaming moisture between her legs glints. Obviously the play of hiding/revealing in and of this work behind the black curtain suggests a parallel with the painting “L’Origine du monde” (1866) by Gustave Courbet when it was in the collection of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, as it, for a time, was hidden behind a black curtain in his bureau, only viewable by request or private invitation.

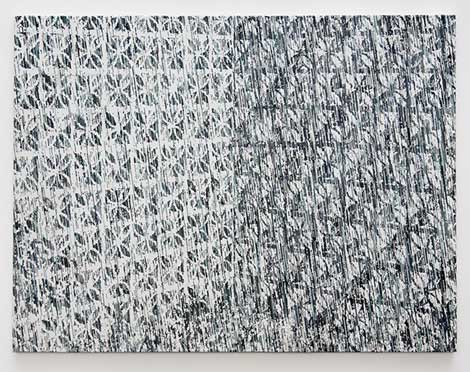

But a post-internet landscape motif dominated the show, with attention-grabbing works that used gorgeous digital prints (Penelope Umbrico), floppy digital painting based on google maps (Clement Valla) or a combination of digital imaging technology and traditional painting technique as with Kevin Zucker’s stunning and visually noisy “Claustra (blue)” (2014).

Clement Valla, “The Universal Texture Recreated (46°42’3.50″N 120°26’28.59″W)” (2014) installation view with nonfunctioning web-cams

There were three robust sculptural combines as well, the hysterically funny vibrating “Terrain Vague” (2014) by Paul Souviron, the elegant screen-meets-fishing-pole combine of Pierre Clément and the slow-time ice-melt composition “Möran: Modular Moraine Maker – Conceptual Art for the Masses” (2014) by Hunter Jonakin.

As noted above, I utterly took pleasure in the fairy camp send-up of high-tech surveillance in our post-Snowden era here. Its ominous mannerist aesthetic, perhaps oddly, reminded me of the school of British fairy painting that stemmed from the late-18th century works of Henry Fuseli, the artist that, by using William Shakespeare’s fairy play Midsummer Night’s Dream as subject, established the basic vocabulary of the dainty fairy/nymph genre in painting. During the epoch of Romanticism the artists Henry Singleton, Henry Howard, Frank Howard, and Joshua Cristall all carried on the tradition in small-scaled fairy works. This pixie approach to the land is most enticing for the show’s portentous concerns with ephemeral perception and I was reminded of Daniel Maclise’s dark nymph painting “The Disenchantment of Bottom” (1832) with its depiction of an ominous but frisky fairy ring of sprites, circuitously and torturously opening the eyes and ears of the central figure.

But, and even given the limitations of the gallery, the curators could have thought about modes of net art inquiry a bit more historically, rather than simply tongue-in-cheek sociologically. Perhaps they could have put a bit more stress on artistic responses to the ominous anthropocene context of our network of perceptual apparatus (and its social organization of modes of knowledge) even as Claire Colebrook has suggested that we have always been post-anthropocene.

On the web at http://www.xpogallery.com/HH/HN/

and physically at 17, rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth 75003 Paris (appointment only)

Closed November 26th, 2014