I have an ongoing conversation with Karen Finley that operates on several levels, one of which is simply her public conversation; i.e., the level on which her work has made its enduring imprint on the culture and more specifically the phenomenon of cultural trauma.

Our “live” conversation has been going on since 2015, around the time of her The Jackie Look performances in LA and the companion “Love Field” gallery show, in which she broke down the “Jackie” narrative—the discrete layers of trauma bound up in the interwoven narratives of Jacqueline Onassis’ lives—into its most resonant incidents, performances, props and gestures.

There’s an interesting resonance to her work right now in that, for many of us, the last four years have been a period of unbroken cultural trauma, magnified by an unparalleled political trauma and an environmental trauma without precedent afflicting the entire planet. The Covid-19 pandemic and attendant shutdowns in New York, California and points between have given an additional dimension to her projects as her interactions in the public sphere have migrated to electronic screens and cell phones.

Not unlike a billion or so of my fellow earthlings, I have an off-again, on-again relationship with social media. Off Facebook (mostly), and on Facebook-controlled (alas) Instagram. Although Finley is most celebrated for her performance work, the often stark pictogramic imagery that has often accompanied her published transcriptions and parable-like narratives and prose-poems, summarizing their deep psychological and cultural deconstructions, continue to show up on her own Instagram feed.

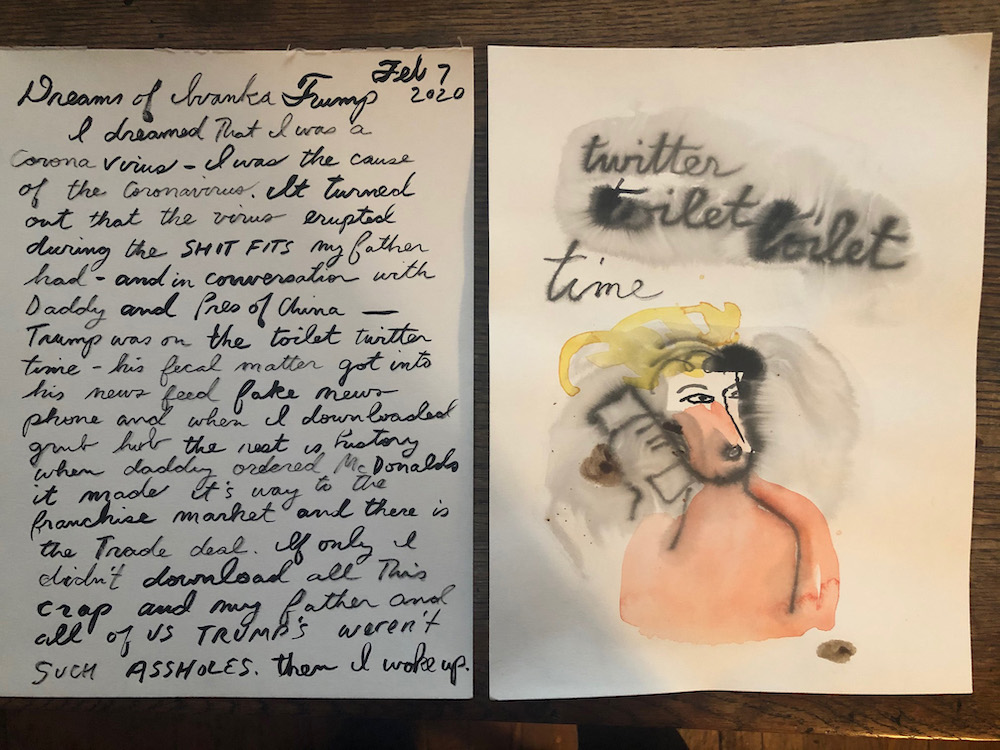

Not long before CV-19 hit New York like a cyclone, she had a series of drawings, entitled “The Dreams of Ivanka Trump,” that seemed to feed off the energy from her 2019 “Sext Me If You Can” series. But sometime around the vernal equinox, the feed abruptly shifted to word drawings in watercolor or pen and ink that placed a single word, sometimes burnished with color or a coppery gold, in a shadowy gray, miasmic field: Covid, mask, corona, quarantine; and so forth. These gradually gave way to short phrases, often laid out on printed pages—pages ripped from old poetry anthologies, children’s storybook pages, calendars, cookbook recipes, advertising, flash cards, sheet music—which might sardonically emphasize or ironize the word or intention behind it. More often, though, the message has been pretty direct: Scrawled vertically across a telephone message pad in one such post (with each message slip marked [To] ‘Trump’/[From] ‘Fauci’ (and signed by ‘Pence’): SHUT / THE / FUCK / UP.

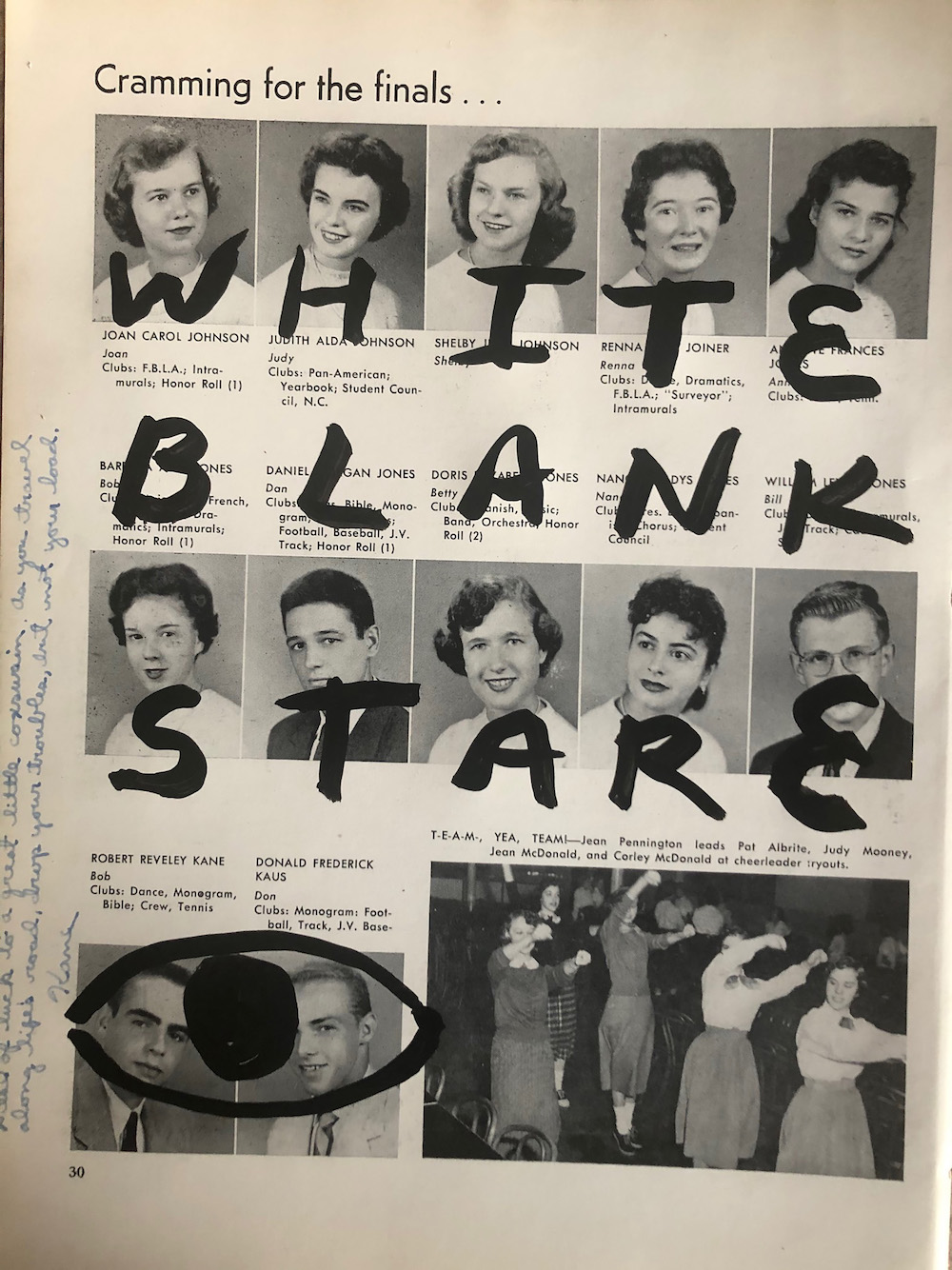

There are shifts in the feed that reflect the mood or the moment, the events pressing in on all of us—though they can sometimes take us by surprise. As with almost anything that shows up on one’s mobile device, much depends upon when the image is viewed. Awakening to Finley’s IG post, White Blank Stare (2020) after some days away from my last digital encounter, I found myself sorting through the trauma of youthful repression underlying my default resting bitch persona, rather than the unconscious white privilege the image (at second glance) clearly addressed. It was at some point into my second cup of coffee (and laughing at myself), I decided it was time to catch up with Karen Finley.

It was more than a month later, not long after the Republican National Convention, when we finally caught up via (what else?) Zoom. After a bit of my own contextualizing, and the recent context of her Instagram (by way of Michelle Obama: “It is what it is.”), we picked up where we left off.

Jackie at the Biltmore, The Jackie Look performance series, 2015, photo by Violet Overn.

Ezrha Jean Black: So where are we now? Where are you now?

Karen Finley: I think that’s what we’re all kind of asking ourselves. I have a double consciousness of where we are now. I have the day-to-day living of just experiencing what we’re all going through under the pandemic and through the regime of Trump, and the day-to-day realities of what is happening in ways I’ve never experienced in my life: with the pandemic, with the protests. Although I did grow up with protest, looking at the extreme violence coming from the leadership, from the White House, the authoritarian rule with the continuing lies—yes, I lived through Nixon, the FBI, the police state we’re all aware of; but in this moment, we’re in desperate times. Yet I am inspired by what has been happening with the protests. And since I’m not able to be putting a lot of my energy into performing, the urgency is invested in the response I create with my artwork. I’m responding from a kind of social critic’s perspective, but also narrowing it down to something very specific. It’s an artist’s perspective as kind of a historical recorder of the times we’re living in. It looks quick and spontaneous, but it does take a certain amount of thought and practice in getting it—to look at the idea, to manipulate the subtexts, so I’m layering it over images in terms of the political work. Or even, let’s say, what I was doing today, which came out of the conversation we were just texting each other about, thinking about the RNC and looking at the portrayals, the costuming, the gender presentation for the Trump women—which almost went to the level of a costume horror show. All of the women had this Night of the Living Dead or Frankenstein kind of look with the black eyeliner; and with Melania, her eyes set back to such an extent. They looked like something out of the Addams Family—and that had comedy in it—but it almost looks like Morticia.

That might be giving them too much credit.

It’s like a horror show. And I was thinking of this idea of the Dark Shadows, the Trump Shadows. So that’s what I wanted to be doing today. I think they really are projecting a kind of horror family, the monsters that they are. There was a sense of monstrosity in the way that they presented themselves Thursday night. Besides their action now, that you really see …who was the Trump girlfriend who spoke?

Nightmares of Ivanka 2, 2020

You must be referring to Kimberly Guilfoyle. Yeah—she was something!

[Then ensued a brief deconstruction of the Guilfoyle Evita/Bananas/The Maids performance.]

And also Melania had that khaki-green outfit she was wearing—it was like military garb.

The whole thing looked a bit militarized. And of course she had to mow down half the Rose Garden to be a better backdrop for her new military look.

It looked like it was absent of nature, like they’d removed it.

Well they removed that entire row of crabapple trees.

[We then thrashed out the Melania-Ivanka psychological dynamics for a minute or so, while we practiced shade-throwing eye rolls.]

It’s horrific; and I’m so concerned about taking this situation and making art out of it. What are these borders of art as an escape, an entertainment, as this space within which it’s palatable to be creating this work; where it’s decorative—what are those places?

But I’m just interested in hosting it. I’ve been doing much more work than that. But I don’t want to put everything on [Instagram].

But there’s a consistent through line. It’s not a gesture, it’s not simply a word. You’re really deconstructing it, following every implication of the word, gesture, image—breaking it down, exploring it at the most basic psychosexual level—and I think you have to go there, because what we’re addressing here is this kind of authoritarianism that has never been so nakedly exposed. Certainly not like this—in lights, against the most officially sanctioned stage in the world.

I’m not necessarily doing it to be converting people, but I’m trying to offer a way of taking a deeper look—to do what art does. I feel that’s part of my job as an artist, and I take that job seriously. Can I say that it’s part of my artistic service? And because I’m not able to be performing—it’s not about performing for the camera, my voice—I’m not interested in putting me in there. It’s about what I’m inspired to be doing now within the visual work right now.

I will say that I look at these things as once upon a time I looked at the drawings, sketches in the book versions [of collected performance work]. In that I can see performance coming from this. In that it goes from a word to a phrase to a kind of poetic fragment, to a kind of chant, or incantation, through to fully fledged performance. You know how to evolve these things.

I think that has always been part of what my creative response has been.

I was just recently speaking with the choreographer Miguel Gutierrez about the NEA (he’s doing a series of podcasts—so I had to re-live that period again) and thinking about artists’ responses in the 1990s. What seems to have happened in a strange way is that more young people are adapting methods we were developing then. So it’s more familiar, easier for me, for them to be doing it. So there’s a lot of incredibly interesting work going on right now, and I’m inspired by it.

[Finley singled out two other artists—Amy Khoshbin and John Sims—and we discussed their work briefly.]

So that‘s the contrast—between the familiarity, the politics of the times—whether you go back to the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s, Vietnam war, Iraq war, the Civil Rights Movement—and the art and response coming out of it. I’m not surprised. I mean I’m devastated. But there’s a familiarity. The latest [performance] work I’ve been developing over the last two years was about a certain paralyzing trauma I see being acted out—sometimes by people you know or are acquainted with. They behave as if they were in agony, traumatized, can’t leave their houses—just refusing to look at what’s happening. They can’t believe what they’re seeing in the news and are completely paralyzed by it. And I find that’s just such a form of whiteness. I mean, where were they? ‘Where were you during the Reagan years?’ Or, looking at the Bushes—getting us into the [Iraq] war. Or thinking about the FBI and everything that they have done to so many people, from the Black Panthers to protesters. You want to see a horrible time? That was horror. People get almost nostalgic. People saying, ‘Oh my god, I miss the Bushes; I miss Laura so much.’

[This stops me dead in my tracks for a split second. ]

Karen Finley, photo by Midge Wattle.

Wait—but these aren’t really pals, people you know.

No, but they’re people that you can see, who have the sense that this time, what’s happening now, has never happened before. I think this is a feeling you see in different places throughout America.

Because there was the veneer of civility that, thanks to people like Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon, has suddenly been violently ripped away. The veneer that masked the actuality of, maybe not kids in cages, but black mass incarceration—a reality, an ongoing reality. There’s no dressing it up.

But it could also be part of my denial, too. I mean it is a horrible time, so you have to watch out for this sense of, ‘Oh it’s been like this before’—that’s a kind of denial, too; you have to focus the determination to make sure that there’s accountability. And I do have a real fear, with this election, of it becoming more authoritarian—I have real fears about the election. There is a real difference between having him [Trump] in that office, that regime, and Biden and Harris. And I’m aware of their histories.

[We briefly discuss their political, prosecutorial histories here.]

Both of them. I’m rolling my eyes here—like Melania!

Yes, both of them. And Anita Hill—there’s a lot there.

And there was a lot more there; and we carried it forward a bit, from politics, to climate change, anxiety—and the humor and perspective we use to pull ourselves through it.

While Finley’s next print and performance works are still in development, her Instagram feed continues: @the_yam_mam—a must for this new-old age of anxiety.