The Los Angeles River is a permanent topic of fascination for artists in this city. In order to establish the city, bureaucrats and businessmen fought to colonize this humble waterway. They tore it away from Indigenous people, encased it in concrete, then rerouted it past the rancheros and into the burgeoning metropolis.

Even if one never visits the Los Angeles River, its presence has informed freeway construction, neighborhood character and the local ecosystem. These relationships are explored through “Brackish Water Los Angeles” at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), part of the Getty’s PST Art: Art & Science Collide bonanza. The show, co-curated by CSUDH University Art Gallery Director Aandrea Stang and the artist Debra Scacco, grew out of a five-year collaboration, which included courses about art and water, and student field trips to the river and other estuaries across the city.

The show’s titular term, “brackish water,” refers to water that is neither fresh nor salty. Usually, this state of limbo occurs when rivers meet the sea. Brackish ecosystems tend to be muddy, swampy and hostile to humans. Because they are an eyesore and can’t rake in revenue through leisurely activities, they’re often paved over. Sites of brackish water can be found all over Los Angeles County. Torrance, right in CSUDH’s backyard, has a treatment facility that desalinates brackish water, making it potable.

“There are going to be different instances of brackishness, where the sea is infiltrating the land so much, it could potentially threaten drinking water sources,” she explained in an interview. “It’s something that we’re going to hear more about, unfortunately, due to the climate crisis.”

Modern research, however, shows that brackish ecosystems are also protective spaces. It’s where salmon lay eggs, and its porous soil absorbs and stores water, which prevents flooding and keeps the area lush even during times of drought. Stang and Scacco’s class taught art students the science behind brackishness, and invited hydrologists, environmentalists and marine biologists to campus so they could understand how the phenomena impacted their own lives.

“We acknowledge the students as experts,” Scacco said. “The course was really an invitation for the students to be our research throughout the process.”

Jenny Kendler, Forget Me Not, 2020. Photo by the artist.

Stang enlisted Scacco as a collaborator because she has been making work about the river and memory for over a decade. She has studied the ways the river has moved over time, not as a rushing body of water, but as a wanderer. Sometimes the river was forced to move due to human engineering, as Scacco illuminated in her work Lineage (2022) in which she noted the sites of dams with gold-leaf dots; but historic maps, like the ones referenced in her series “Topographic Works: Los Angeles River” (2015–16), where ink on shimmering Dura-Lar recreates the delicate, straying paths of the river over time, show that it also changed course naturally. Scacco, a first-generation Italian-American who has lived in Atlanta, London, New York City and Los Angeles, finds kinship with the meandering nature of this body of water.

The ethos of her personal artwork translates into the curatorial direction for “Brackish Water Los Angeles.” Some of the pieces include two-tonal photographs from Catherine Opie’s “Freeways” series (1994–95), Untitled #23 and Untitled #24, where concrete highways crisscross the concrete riverbed; a visual poem by the Tongva-Chumash-Chicano filmmaker Isaac Michael Ybara, Ooxono (From Here) (2023) which explores the conflict experienced as an urban native by juxtaposing preserved landscapes with urban infrastructure; and an installation by Alfredo Jaar, who the curators learned about through a student’s research in their art and water class. His piece, Untitled (Water) E (1990) takes the show beyond the Los Angeles River and into the South China Sea. Waves, illuminated against lightboxes, partially block the view of mirrored photographs that depict Vietnamese immigrants held in overcrowded detainment centers in Hong Kong.

“Brackish Water Los Angeles” places these contemporary artworks in dialogue with historical and scientific documents. There are maps of the river, sourced from the university archives, indicating its reach and topography in the early 1900s. F.H. Maud’s tiny, hand-painted magic lantern slides, such as the serene landscape in Los Angeles River, Near Los Feliz, come from the Autry Museum of the American West’s collection. The glass plates, created sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, show the river pooling in a fertile wetland that is now an urbanized neighborhood. And a preserved specimen of a fiddler crab, Uca princeps (Smith, 1870) which comes from the Natural History Museum Los Angeles, showcases the fauna that once thrived in the floodplain. The addition of these pieces makes the exhibition difficult to categorize. It’s situated somewhere between an art gallery and a science center.

“We really like to describe the show as being about the paradox of the in-between,” Scacco said.

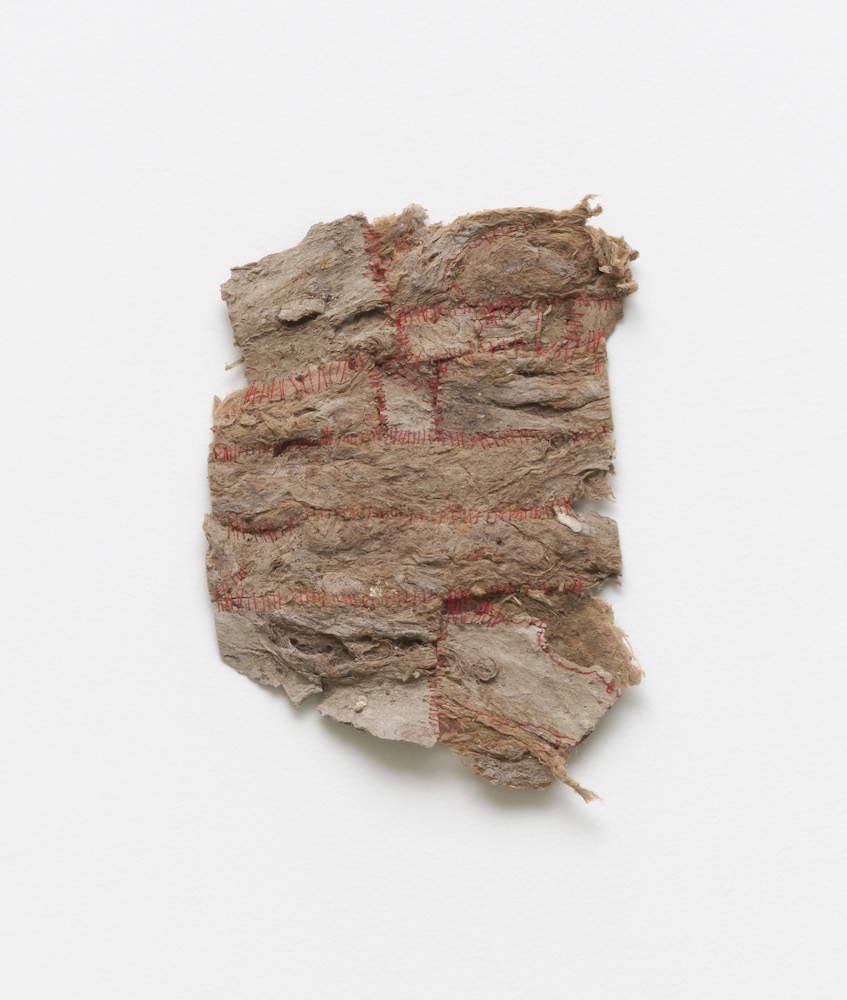

Emma Robbins, LA River Paper, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

While nods to the past are entrenched in the exhibition, it also looks towards the future. The augmented reality piece by Nancy Baker Cahill, Mushroom Cloud LA / Proximities (2022) anticipates a grim nuclear war that will annihilate our environment, but her pessimism is countered by

multimedia work by Metabolic Studio, Portable Wetland for Southern California (2019), which shows how the artist Lauren Bon is ripping up concrete to restore the LA river to its natural state.

“The idea of interdependence is so critical, and it makes me a more empathetic person,” Scacco said. “I want to think seven generations ahead.”

“We want people to leave feeling like they have access and agency,” Stang added. The gallery will provide handouts that highlight local climate justice organizations and activities, so people will be able to donate to them or volunteer.

Stag and Scacco frame “Brackish Water Los Angeles” as a site of transition, mutability and resilience. It can destroy worlds, be a lifeline, and, in the age of climate change, become a political battleground.