Lucio Fontana, the Argentine-born Italian artist best known for his slashed, punctured canvases and lumpy ceramic sculpture, had another less acknowledged side to his oeuvre- his “spatial environments”. Created in the last 20 years of his life, these ephemeral installations represent a unique aspect of his art, casting his better-known works in a new light.

Lucio Fontana Walking the Spaces: Spatial Environments, 1948-1968, at Hauser and Wirth Los Angeles presents nine meticulously recreated installations from this terminal, yet seminal (in its influence on subsequent artists) period in the artist’s work. To say that this work “anticipates” light-based installation art (such as Southern California Light and Space Art) would certainly be an understatement. Fontana’s achievement is only fully appreciated if one continues to check the dates on the works; Spatial Environment in Black Light (1948-1949, for instance, was created when Pollock was painting his drip paintings, but it seems a world away from that era, more a part of the multi-disciplinary art of the 1970s and after. Closed, like virtually all museums and galleries due to COVID-19, the show will hopefully be extended; it’s a huge, museum scale undertaking that will most likely not be repeated and should not be missed.

Many of the works seem to almost be embodiments of painting transformed into installation art. The aforementioned Spatial Environment in Black Light seems distinctly like an abstract painting come to life; in fact, photographs of it can look more like a painting than an installation. The piece utilizes 10 paper mache’ sculptures painted in fluorescent colors, paneled walls, and 6 black light lamps, creating a complete sensory environment of organic forms that slither through space. It’s comparable formally to the abstract expressionist paintings of Kandinsky, but in a three-dimensional environment.

“Spacial environment with neon light,” (1967). Courtesy of Fondazione Lucio Fontana.

Later works, such as Spatial Environment with Neon Light (1967) are much more minimalist in their sensibility. In this piece, the walls and ceiling of the room are covered in pink fabric and a single pink neon crystal tube meanders across the room, suspended near the ceiling. The ethereal pink glow that the effect of the light and fabric together produces feels distinctly primal, as if conjuring up a return to the womb, the very beginning of life. By reducing the elements of the piece so drastically to a glowing color environment, the piece also feels like an extension of the effect one gets in an installation of Rothko paintings — color as pure expression.

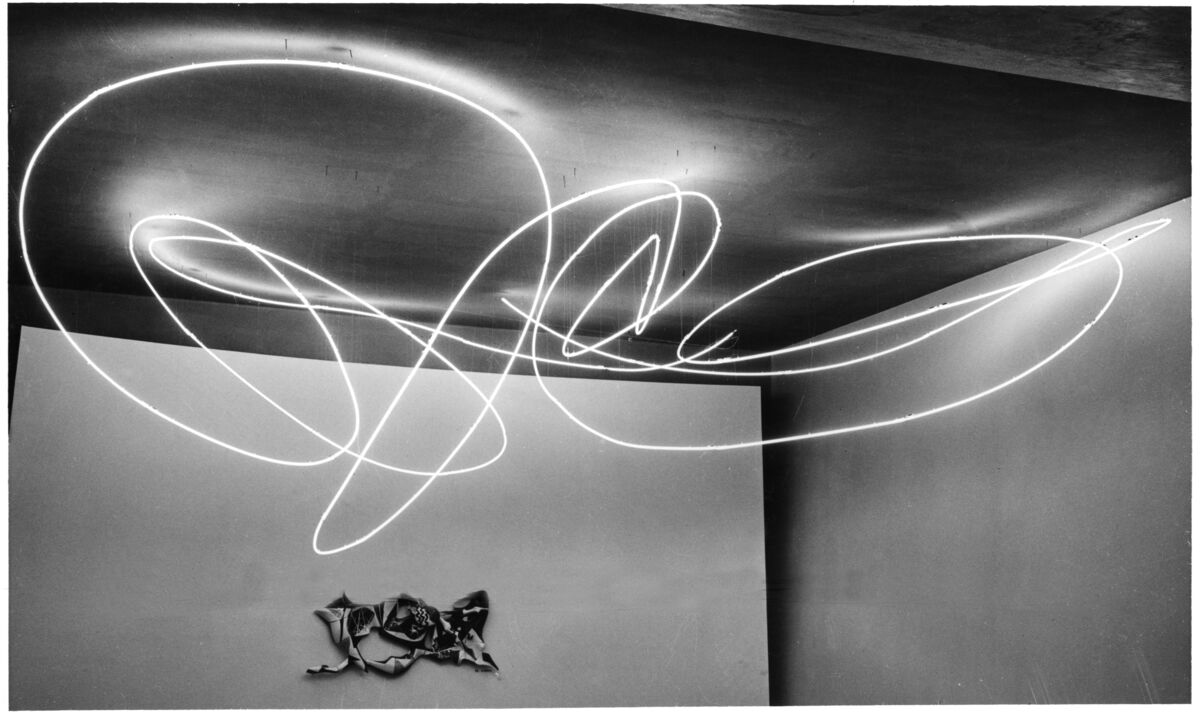

At nearly 30 x 40 feet, Neon Structure for the 9th Milan Triennale (1951) is the largest installation in the exhibition, a gigantic scribble drawn in stark-white neon and installed high above viewers heads where it weaves through the wooden open-beam ceiling. The contrast between the symmetry and structure of the architecture and the free-wheeling exuberance of the neon is striking; the piece both integrates with and profoundly transforms the site. It was originally shown in Milan, where a version of it resides today on the top floor of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna. It can be viewed there against a breathtaking view of the Milan Cathedral, creating a strange and appealing comingling of Medieval and Modern sensibilities.

“Neon Structure for the 9th Milan Triangle,” (1951). Courtesy of Fondazione Lucio Fontana.

Some of the installations are quite disorienting, such as Spatial Environment: ‘Utopia’, at the 13th Milan Triennale (1964), in which the viewer must navigate through a cramped corridor bathed in red light, and pass over a kind of hill covered in thick carpeting; it’s difficult to avoid knocking one’s head on the ceiling as one moves over the hill from one part of the installation to the other. Spatial Environment (1966) similarly has 2 rooms that one must duck way down in order to pass between, on a floor made of polyurethane foam covered in rubber. It’s as if Fontana wanted to make the art experience difficult for the viewer, in the same way that much modern and contemporary art presents challenges and provocations to the public.

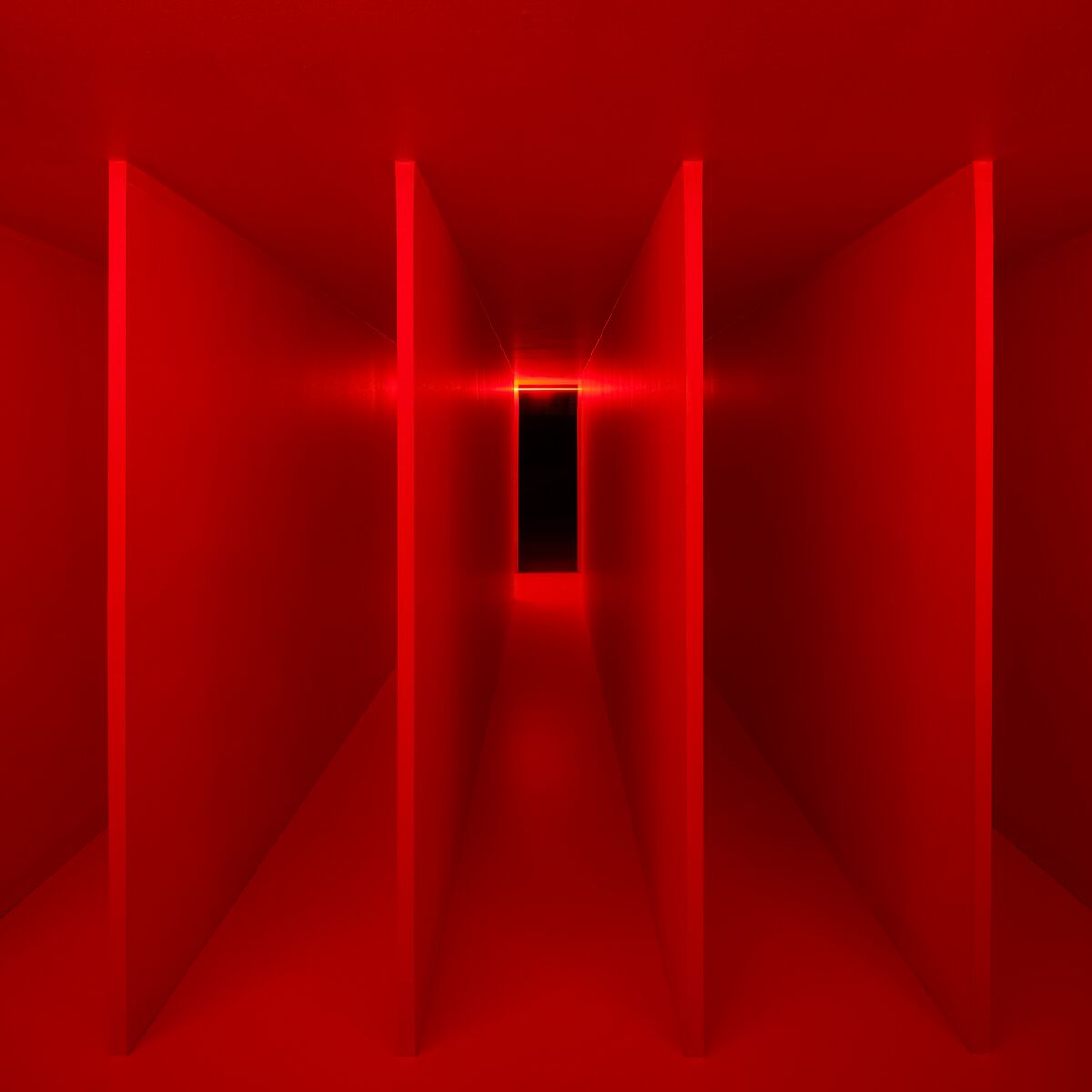

Other works recall those that younger artists created in the period immediately following Fontana’s death. Spatial Environment in Red Light (1967) consists of 6 corridors painted vivid cadmium red light through which the viewer navigates. The color, repetition and severity of the work made me think of Donald Judd’s sculpture- if he had ever made installation art, it might have looked like this. Similarly, moving through the narrow spaces evoked the memory of Bruce Nauman’s Green Light Corridor (1970), a study in claustrophobic response.

“Spacial Environment in Red Light,” (1967). Courtesy of Fondazione Lucio Fontana.

It’s tempting, although simplistic to link Fontana’s installations to the development of Southern California Light and Space Art. There is most likely no direct connection- I have never heard artists like James Turrell, Robert Irwin, or Douglas Wheeler cite Fontana as an influence, and he is not even mentioned in Jan Butterfield’s definitive book on the movement. Although in both cases, the basic elements of light and space are used to create an immersive artwork, an important difference is the artists’ motivation for creating the work. Fontana was more of a mystic; his penchant for creating holes in various materials was an allusion to the void, which also informed his installation art. The Los Angeles artists, especially Irwin and Turrell, were more interested in using light and space as a means to investigate perception, such as the way Turrell’s Ganzfeld works can cause a deep space to appear flat. Having said that, after seeing Fontana’s Spatial Environments, resurrected together as kind of retrospective, I will never think of LA Light and Space Art in quite the same way.

Lucio Fontana, Walking the Space: Spatial Environments, 1948-1968

Hauser and Wirth Los Angeles, 13 February-12 April 2020

0 Comments