After success and critical acclaim, Philip Guston somehow bravely abandoned his signature style. His transition from abstract expressionist to neo-expressionist (before there was such a category) was heretical. In ab-ex lockstep he had been part of the American exhibition that toured Europe; as Eva Cockroft had documented in Abstract Expressionism: Weapon of the Cold War the exhibition was as propagandist as Radio Free Europe. Guston’s annis mirabilis was 1971, and Hauser & Wirth’s exhibition dedicated to the artist documents that year.

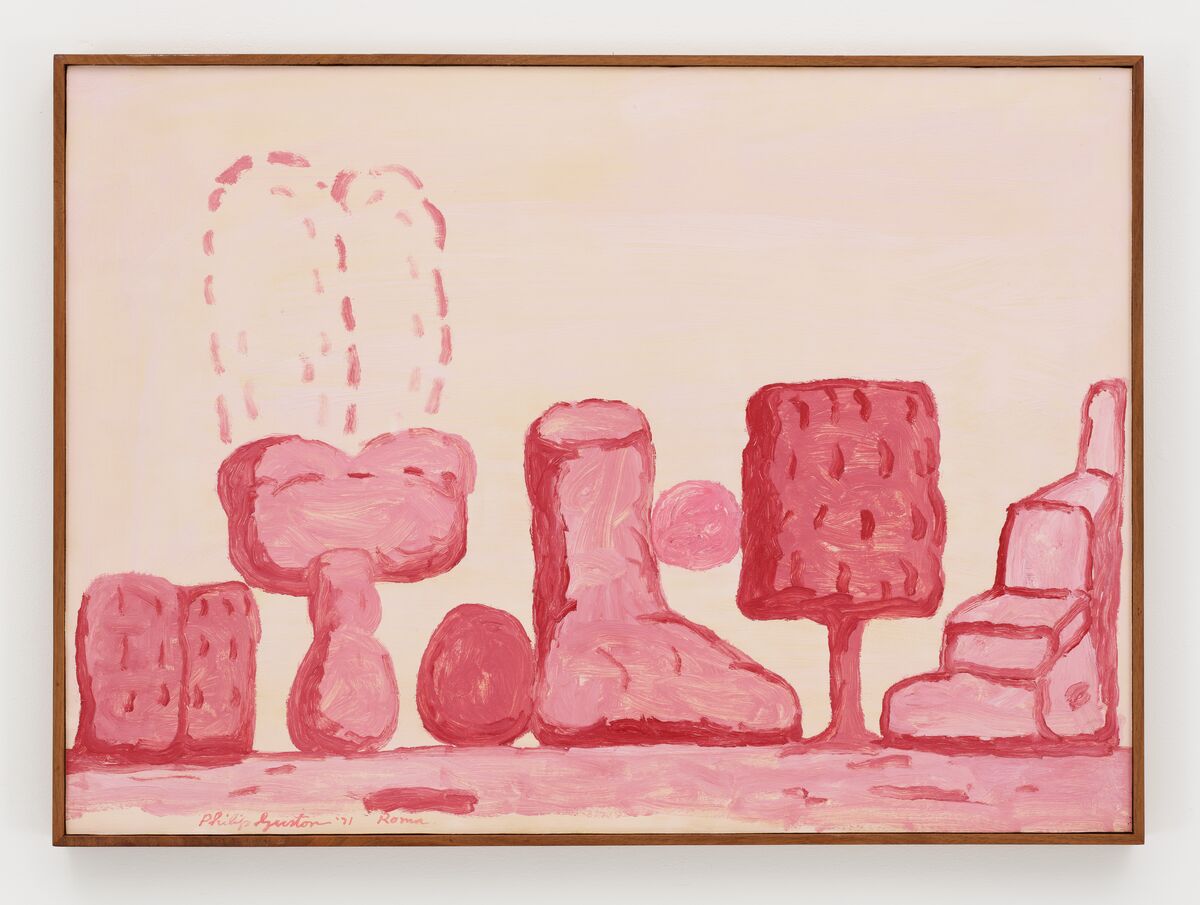

Philip Guston, Untitled (Roma), (1971), 49.5 x 68 cm, oil on paper mounted on panel. Courtesy of the Estate of Philip Guston.

Guston’s rejection of painterly orthodoxy could be told in a pair of works on view—just two of the more than 150 on display. Made during Guston’s fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, the foot rendered in Untitled (Rome) appears classically regal yet fractured and weathered. It references a fragment from the Colossus of Constantine, a former four-story statue of the Roman emperor who converted to Christianity. Untitled (Orange Shoe), however, is a vivid rendering of a scuffed and clunky hobnail boot. These two oil-on-paper works could serve as icons contrasting the vain and humble ambitions of the two; the emperor who dreamed of being a god and the princeling who chose to be a laborer.

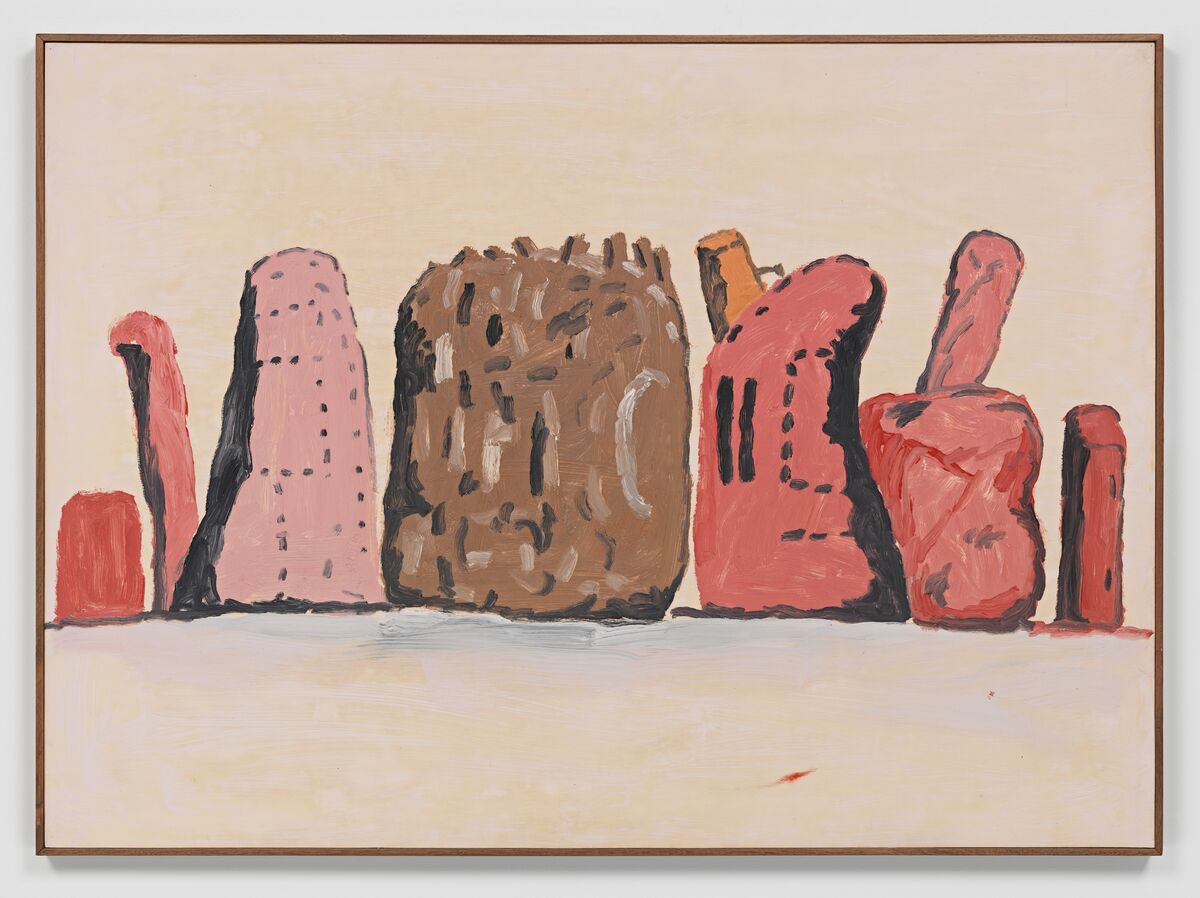

Philip Guston, Untitled (Roma), (1971), 55.3 x 73.7 cm, oil on paper mounted on panel. Courtesy of the Estate of Philip Guston

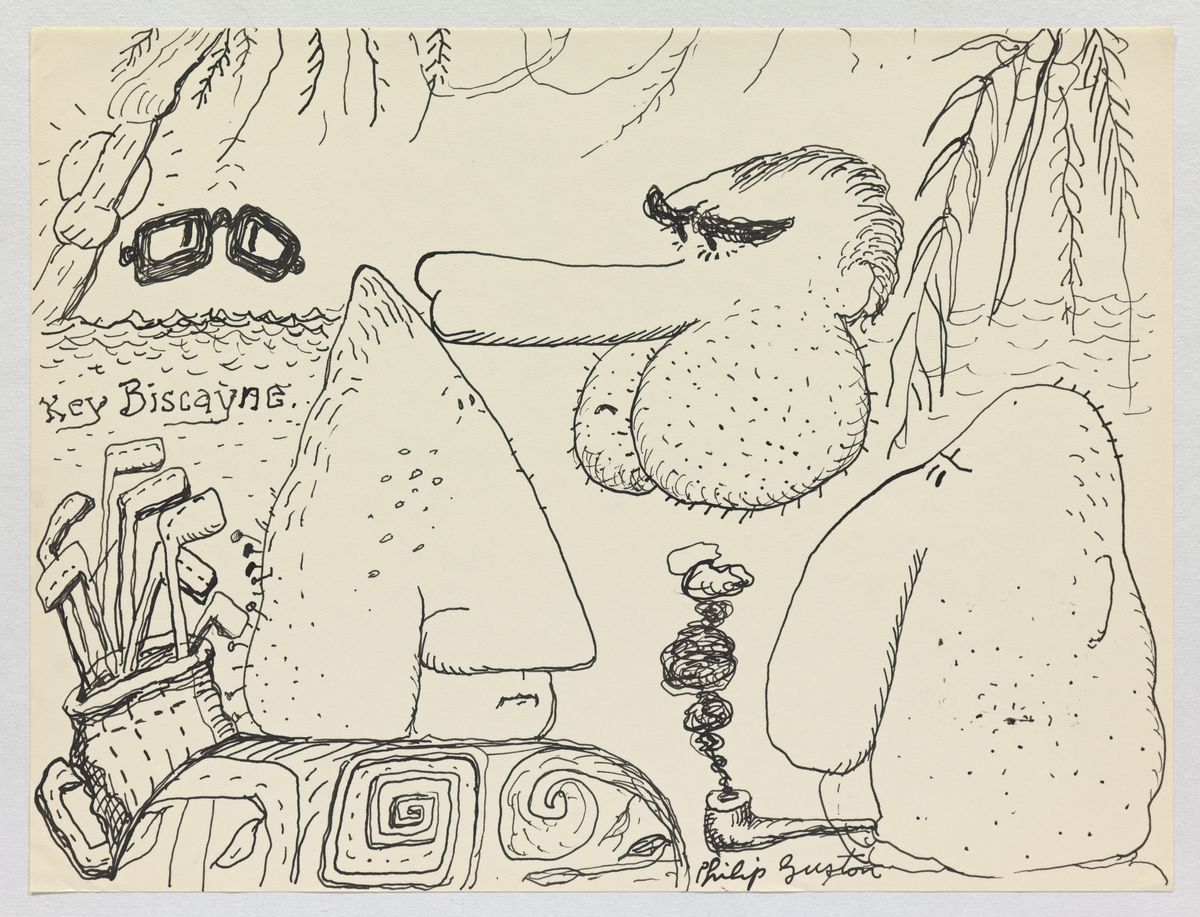

In addition to the Roma series are the disturbing caricatures of Richard Nixon, the Poor Richard drawings. His ambitions are also made apparent. In one of these ink drawings (there are seventy-four of them), Nixon and Agnew are shown as colossi, grand as pyramids upon a sandy plane. Another has Nixon sleepless, his blanket pulled nose high while he stares at his Whittier College pennant. His blanket is tent-poled by his enormous erection as he plots to avenge every slight that was ever made against him. Tricky Dick is also one of Guston’s infamous Klansmen, recognizable beneath his hood as there is no hiding his priapic nose.

Philip Guston, Poor Richard, (1971), 26.7 x 35.2 cm, ink on paper. Courtesy of the Estate of Philip Guston

Few large oil paintings are included, yet his oil sketches and ink drawings make their absence nearly unnoticeable. What stands out is Guston’s insistent devotion to dissatisfaction, whether in the Klan images—first begun in the 1930’s—or to political commentary and resistance that remains achingly raw and minute-ago contemporary.