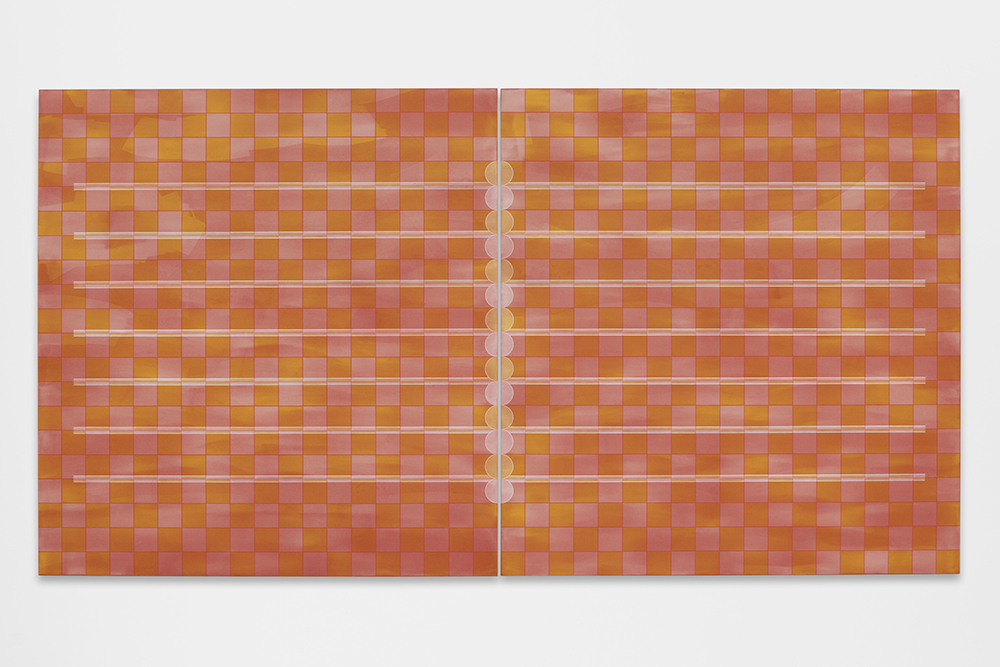

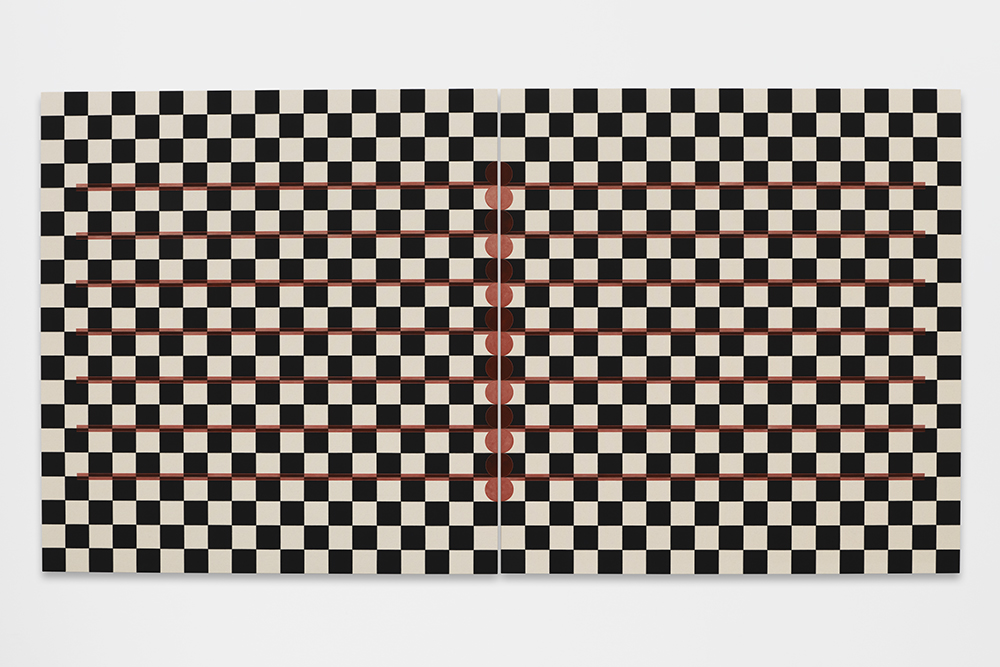

Like the checkerboard floor of the gallery in which they are displayed, the two largest works in Hanna Hur’s exhibition, “Two Angels,” are gridded and divided down the middle. However, unlike the somewhat haphazardly arranged gray, black and white tiles at Kristina Kite, the canvases are nearly symmetrical with a slim gap of negative space between the two panels of each. Angel (all works 2023) is colored with candied pink and orange squares, red colored pencil outlining the squares. Angel ii is black and white with seven red stripes mirroring those of its roommate.

The paintings are installed across from one another, hung closer to the floor than the ceiling. With their addition, the room suddenly feels smaller; the paintings tug at each other’s wings. A slim wooden bench divides the gallery, one end on the black-and-white part of the tiled floor and the other end on the gray section. The presence of the bench establishes a particular vantage point from which to view the works, either with your back to one or the other or turning your head between the two. The installation invites, and nearly insists on, a contemplative encounter with the works, further emphasizing their spiritual implications. The bench points to the back room where there are six other works on paper that demonstrate the development of the gesture that manifests in the larger canvases.

Hanna Hur, Angel ii, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist and Kristina Kite Gallery.

As I write this, my slight dyslexia keeps exchanging the order of the letters in the word angel. I keep writing angle. The two things are seemingly at odds with each other: “angle,” a measured intersection between two lines, and “angel,” a benevolent spiritual being whose presence is ethereal and ambiguous. From one emerges the other; the “image” of an angel surfaces on top of the grid. Though it’s hardly an image, rather a suggestion through symbols: Semicircles along the inner edges of the canvases form a kind of body down the middle and horizontal lines extend to the outer edges suggesting its wings. Hur has left a gap between the two panels, as if for some divine spirit to take up residence. The meticulous precision with which the grid is produced is broken up by this mysterious valley between the work’s panels.

The labor put into the construction of the grid is thus the record of time and the counting of squares, and of the almost phantom presence of a ruler. Hur begins most of her works with this repetitive act. Like that of a writer doing research or taking notes, it’s a rigorous, quantifiable activity from which something more miraculous, a painting, emerges. In Angel, the acrylic of the underpainting has the effect of a photographic print, sun-faded. But without our having witnessed the repetitive gesture of their construction, there is something angelic about the works, something that seems to appear out of nowhere. That, perhaps, is the inexplicable core of any creative process that begins with a blank canvas.