For New York based multi-media artist Hank Willis Thomas, art and politics are intertwined. He draws from history, advertising (he made a series based on the Nike swoosh), and current events to create works that address issues of racial injustice, identity politics, and more recently, the meaning of freedom. With formal integrity and conceptual savvy, the impeccably crafted fabric pieces in the exhibition Another Justice: Divided We Stand are assembled from American flags and prison uniforms and literally “investigate the fabric of our nation.” Across the works, Thomas juxtaposes the red and white stripes from the American flag with prison garb in various colors. While works like A New Constellation and Imaginary Lines (all works 2021) separate and repurpose the stars and stripes, it is the text-based pieces carefully cut and collaged from prison uniforms and flags that are the most compelling.

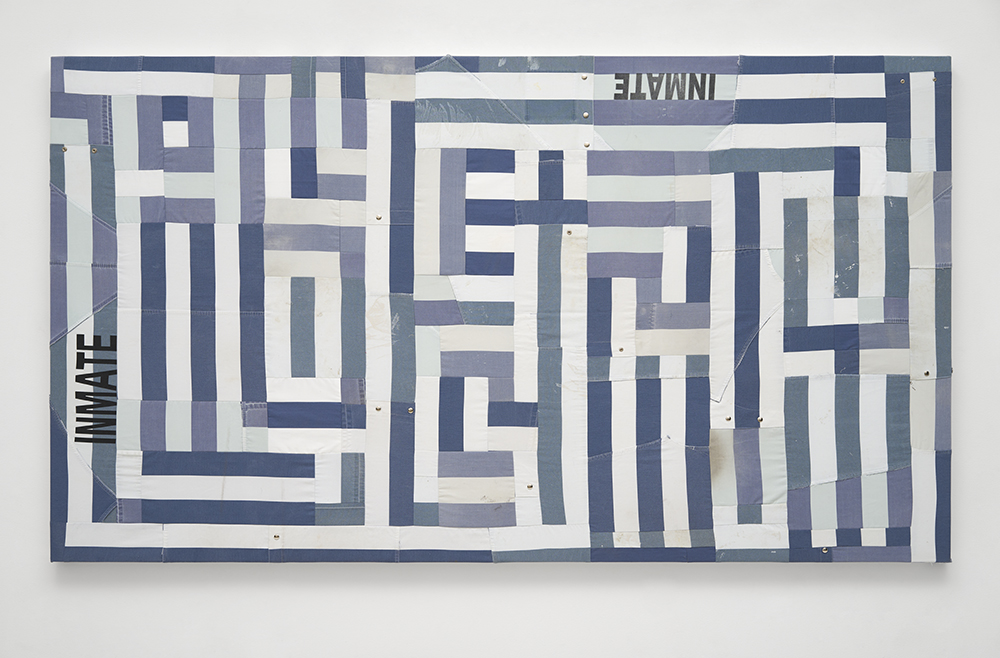

The huge Land of the Free (orange), appears at first glance an intricate maze made from interlocking strips of fabric culled from prison uniforms and fashioned into a landscape of concentric shapes. As the eye traverses the composition and begins to separate the red/orange from the white, letters and then words—Land of the Free—begin to cohere. Once recognized, (akin to the duck rabbit visual illusion), it is difficult to unsee the letterforms. Thomas plays with this and other dualities like the fact that while America is considered “the land of the free,” it also imprisons more people than any country in the world. The reference to prisoners is more overt in Liberty (blue) and Capital (green) where the word “INMATE” from the uniforms is included at different corners of the compositions. Yet the words “Liberty” and “Capital” slowly emerge from the graphic abstractions, and Thomas’ juxtaposition becomes more evident.

Hank Willis Thomas, installation view, 2021, photo by Flying Studio, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist and Kayne Griffin, Los Angeles.

The words entangled within the stripes of these works explore the meaning of freedom and liberty, as well as issues of discontent within our so-called “land of the free.” The artist questions—who are “we the people” and what does “justice” really mean—as he dices prison uniforms and dismembers flags, a gesture some would consider sacrilegious, as well as a violation of the proposed Flag Desecration Amendment. That aside, in his carceral tapestries, Thomas draws parallels between prison bars and the stripes on the flag, calling attention to injustices and inequities within prisons as contradictory to the supposed freedom “America” offers.

The notion of conflict continues in the gallery courtyard with Strike, a polished stainless-steel sculpture depicting two giant arms that burst forth from the gravel. One arm raises a police baton ready to strike, as the other attempts to hold it back—referencing the 1934 lithograph titled Strike Scene by Russian-American painter and printmaker Louis Lozowick—as a gleaming, symbolic protest.

Thomas investigates and reveals how justice really works in this “home of the brave” where people of color are disproportionately imprisoned. In a tense and potentially change-filled moment in history—burdened by a pandemic, continued racial tensions, and the effects of climate change—the artist employs American symbols to undermine what they supposedly represent.