I left Gregg Bordowitz’s recently-closed exhibition at The Brick, “This is Not a Love Song,” thinking the same thing as upon leaving The Brutalist: “I didn’t know it was going to be so Jewish.” In both, the artist’s Jewish identity weaves through a deep consideration of form as such. I might even cheekily add that in both cases, the interest in form manifests in concrete specifically. The Brutalist’s eponymous brutalist, László Tóth, uses concrete to maybe (?) represent the suffocating brutality of Auschwitz. Bordowitz, on the other hand, has a longstanding interest in concrete poetry. This is not a review of The Brutalist but one further comparison is perhaps warranted. The film’s climax centers on the completion of Tóth’s brutalist church/community center and the antagonist presumably committing suicide somewhere inside, turning the monumental structure into a tomb as well. In an epilogue, Tóth’s niece describes the building as a redemptive allegory of Auschwitz. In other words, the film culminates in a tomb for a body that is never shown and a story of redemption for the most indescribable of sins. A rather Christian Judaism, all told.

I bring this up only to contrast it with the approach to Judaism taken by Bordowitz, one more active and paradoxically, more architectural. Bordowitz’s Judaism is not so much represented as it is embodied—a structure for living. The exhibition is anchored by a freestanding wall positioned diagonally in the center of the gallery. Bordowitz’s poem, Bougainvillea Calliope, is affixed directly to both sides of the wall. It is governed by Bordowitz’s self-imposed rule that each line be exactly ten syllables. Lines such as “LASAGNA HOLIDAY IMMIGRATION/ HOSTILITY RECIPE LEGACY” are illustrative of the poem’s taut blend of the nonsensical, political, and personal. The poem’s balance of formal rigidity and quasi-abstract meaning is paralleled in the print series, entitled Tetragrammaton, hung on the wall, which occasionally obscure sections of the poem. Though they are all abstract, the series depicts the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Hebrew theonym for the name of God. Here too, the formal constraints of language overflow with an irrepressible passion.

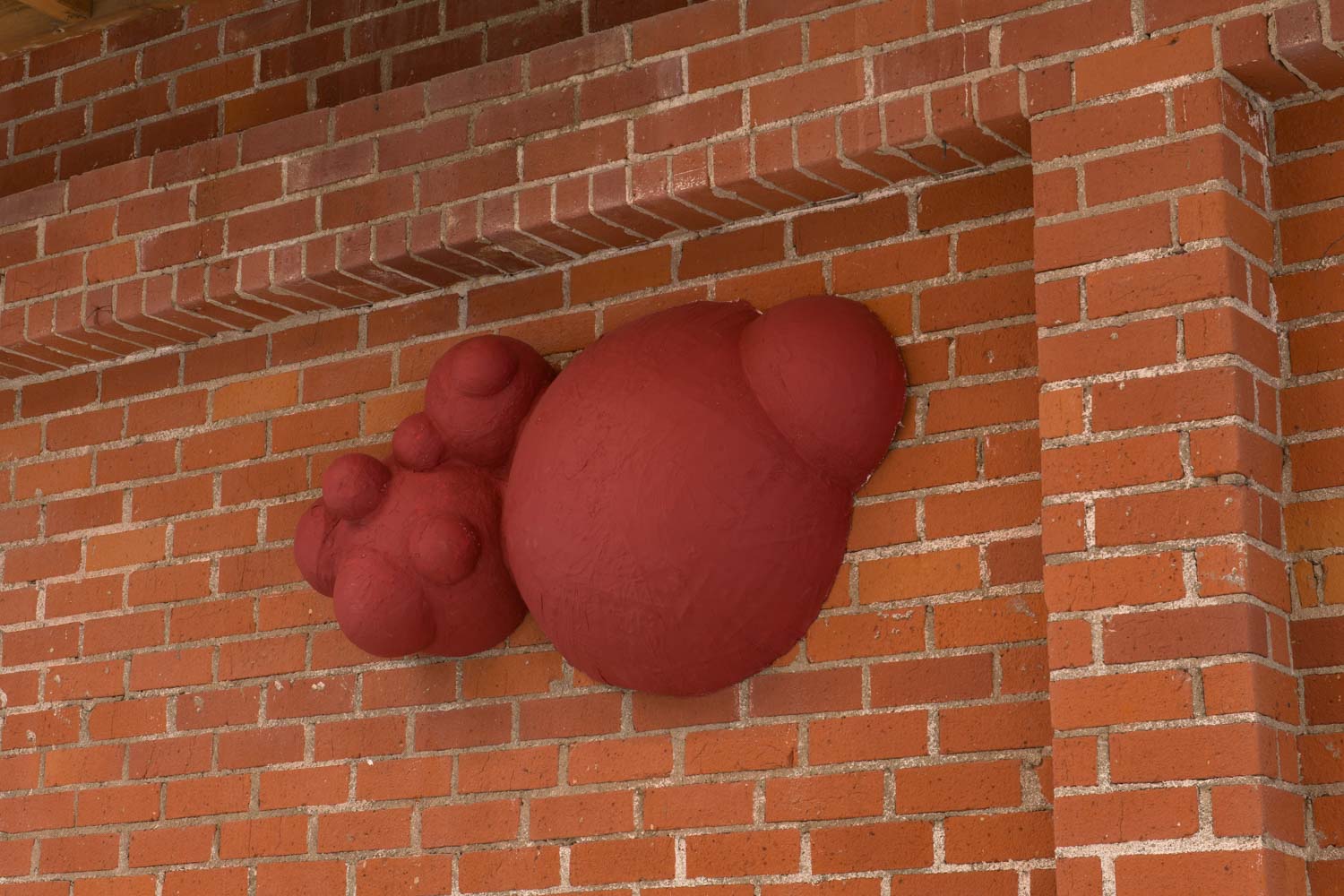

Gregg Bordowitz, “This is Not a Love Song,” exhibition view, 2025 at The Brick. Photo: Ruben Diaz. Courtesy of The Brick.

As an academic, AIDS activist, poet, and politically-inclined video artist, language has always been central to Bordowitz’s practice. Here though, the written word functions as a sort of necessary boundary line. The rules it establishes for sensemaking serve to delineate what exceeds it, what cannot be accounted for. In this way, it is not simply an inert representation but a site of energetic activity. Another piece, Continuous Red Line, made of a red strip of tape, running inches off the floor along the gallery’s perimeter operates similarly, linking each element of the exhibition into a whole. The artworks are thus in conversation with one another though this does not require that they find any resolution. The line is perhaps the ur-form of art, representing form as such and the fundamental building block of artmaking. Both the scrawled lines of quasi-legible Hebrew on each print and Continuous Red Line are thus testaments to the line’s dual functions as a form and a process, an idea echoed in the exhibition’s accompanying booklet. There, Bordowitz writes that “form is both a process and a state.”

This is echoed in the exhibition’s curation itself. Placing the wall in the gallery’s center animates the typical flatness of text and prints. Additionally, the wall’s placement forces viewers to ritually circumambulate the work. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heshel, who Bordowitz quotes in the booklet, famously said that Judaism does not build cathedrals in space but in time, through the affirmation of ritual. In other words, form emerges out of communal repetition. This idea is closely related to a central tenet of Bordowitz’s political belief, cultivated through years of AIDS activism with ACT-UP, that the personal is political. Both theories conceptualize the individual’s actions as a fractal piece of a much broader community movement. Both ideas suggest that meaning is found in action itself, not finality. At a moment when Jewish identity is in danger of being essentialized (or concretized) into a hard nationalism, Bordowitz’s work suggests a softer Judaism, one that cannot crack as a result.

Gregg Bordowitz: This is Not a Love Song

The Brick

518 N. Western Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90004

February 2 – March 22, 2025