Light affects perception in ways typically taken for granted: the ability to see and function; moods; sense of time. In lenticular photographs from the series “Day & Night” and “Frolic” (all works 2015), George Legrady recontextualizes family snapshots to blend seamlessly with images of moonlight. These scenes, with their peculiar luminosity, throw into question a viewer’s ability to accurately interpret what is seen.

Legrady exploits to astonishing effect the lenticular printing process, which involves two or more interspliced images and 3D lenses inserted into the picture plane. When viewers move in relation to the picture, visual elements shift. What is seen in Legrady’s photographs—at least initially—are images of his Hungarian relatives, sourced from found 1930s and 40s snapshots. In Day & Night a group of cosmopolitan men and women make the most of a weekend excursion to the mountains of Transylvania, Romania, where they spend time with the local folk. In Frolic, other relatives clad in bathing suits perform for the camera. Legrady’s black-and-white works invite entry into these narratives both because they are physically large and because of their enhanced pictorial depth.

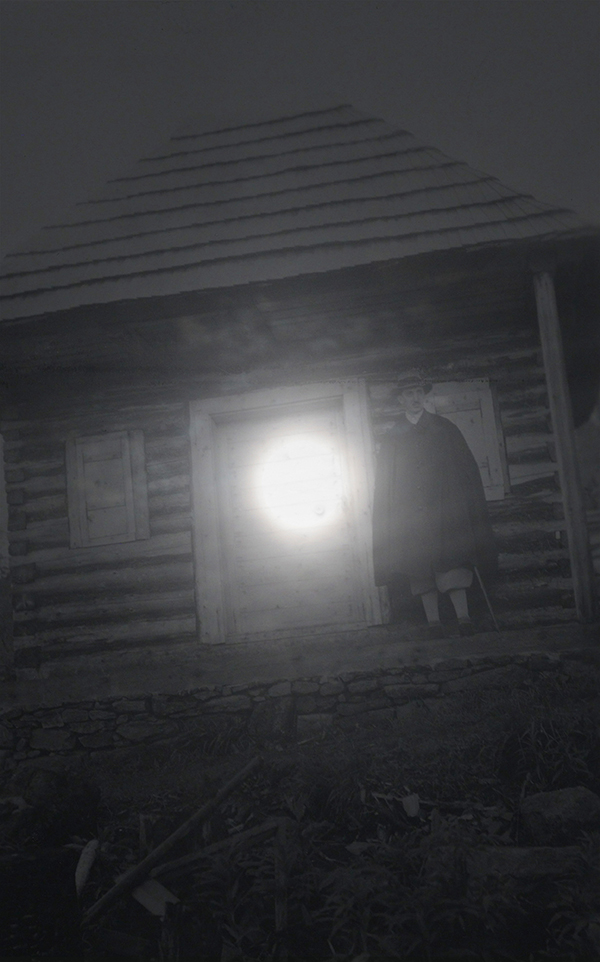

In Day & Night Cabin, a man stands in front of a rustic building, a brilliant orb superimposed over the door. When the viewer stands back, the image turns dark and the sphere brightens. In Day & Night Transylvania Hunt, hunters stand in snow, two boars at their feet. Viewed at an angle, a superimposed white streak appears, like a trick of refracted light. In Day & Night, men and women gather around an outdoor fire, over which moonlight and tree branches are superimposed. The atmosphere, charged with a lunar glow, shimmers. When the viewer steps in any direction, elements in the picture are subdued or brightened, appear or disappear.

In all of these photographs, time is unclear. Is it dusk, midnight, midday, or day and night simultaneously? If optical effects seem like figments of the imagination, then what persists is a kind of twilight. By contrast, Frolic conveys hyper-exuberance. Women and children cavort in a meadow surrounded by trees, playfully striking similar poses. Each activity is viewed from two vantage points. The effect is kinetic, with arms and legs flying, and human limbs echoing superimposed tree branches. A surreal radiance and overlays of color intensify this visual energy.

George Legrady, Day & Night Cabin, 2015 , Courtesy of the Artist and Edward Cella Art + Architecture

The source-images that make up Legrady’s photographs also appear in Anamorphic Fluid, a computer animation activated by nearby movement. Although attention grabbing, this work feels emotionally flat.

Legrady has devoted a career to the intersection of cutting-edge computer technology and fine arts (he heads UC Santa Barbara’s Media & Technology program), but his roots are in film-based photography. Like his contemporary James Welling, Legrady’s unique approach elicits meaning from the medium’s history. Amazingly, the entire history of photography is conjured in his photographs. Maybe all that shimmery moonlight evokes the silver used in chemical processes. In any case, these works feel older than the snapshots they reference. Not only does the viewer confuse day with night, it isn’t clear what year, decade or century it is.

0 Comments