Bruno Schulz’s fantastic stories mesh familial dysfunction, metamorphosis and metaphor, complemented by a body of visual artwork filled with sexually charged imagery with a masochistic perspective. Benjamin Balint presents an impassioned narrative in Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History.

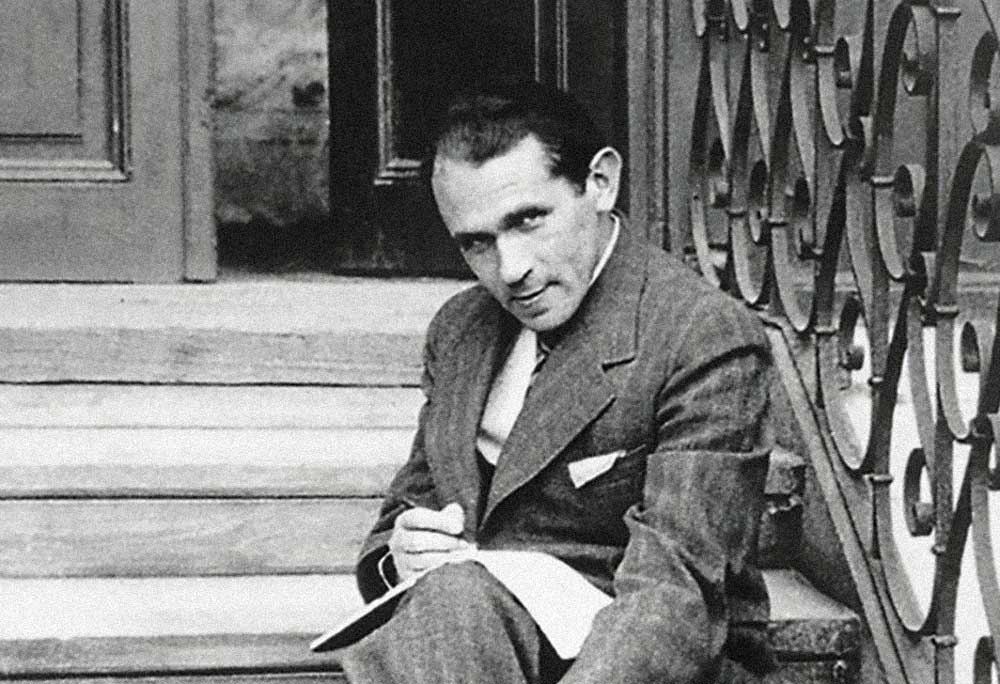

Schulz may have been small in stature and unimposing in aspect, but he was expansively gifted. The success of his literary debut, Cinnamon Shops (1934), was followed by an equally impressive Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937), his only other surviving book. Although he remained a high school teacher in the drab oil town Drohobych (then in Poland, now Ukraine) for 17 years, and was a quirky, self-abnegating guy, he was profoundly aware of his own gifts as a writer, building on the legacy of role models—such as fellow Austro-Hungarian Franz Kafka.

Cinnamon Shops, known in English as The Street of Crocodiles, revealed Schulz’s already depressive nature, rooted in his claustrophobic childhood home, with a tubercular father and other invalid relatives crammed into a flat above the family’s fabric shop in Drohobych. An eccentric cast of characters—notably the formidable housekeeper Adela, the father and Joseph, who stands in for the author—wander at will through convoluted dimensions, heightened by experiments in breeding exotic birds, metaphysics and necromancy.

Schulz’s own personal travails would quickly be eclipsed by the unfathomable horror of the Holocaust, a subject that Balint depicts in unflinching detail. An SS officer, Felix Landau, admired the overtones of S&M in Schulz’s artwork—often submissive figures groveling at the elegant feet of imperious women—and took the artist on as his Leibjude, “personal Jew.” This ostensibly gave Schulz a protected status belied by his ultimate murder—unsolved but likely at the hands of a rival Gestapo officer. He painted portraits of Gestapo girlfriends and completed a number of murals around town, some for the SS casino, and some for Laundau’s children’s nursery, whimsicial fairty-tale scenes.

With colorful scenes from tales like Hansel and Gretel, or a sultry Snow White surrounded by seven devoted, gnome-like dwarfs, the works cast a bit of light into some very dark recesses. Here the twisted fate of these murals takes an unexpected turn—to Israel. For Yad Vashem, the institution of Jewish remembrance located in Jerusalem, the murals represent an important piece of the history of the Holocaust. Yet their use of the term “repatriation” in reference to the action carried out in Drohobych in May 2001, in which Israeli operatives surreptitiously chiseled the frescoes right off the walls, seems strained, at best. With repatriation of artworks at the forefront of ethical considerations in the global museum community, Balint’s work raises complex issues about conflicting rights of ownership.

Balint’s overarching theme of loss persists, touching on “the cold case of the missing novel, one of the literary world’s greatest unsolved mysteries.” The fate of the lost manuscript of Schulz’s final work, Messiah, remains to this date unknown. Balint offers a gripping, nuanced portrayal of Schulz’s world.

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History

By Benjamin Balint

320 pages

WW Norton

0 Comments