I first met Gary Simmons in the early 1990s when he was a student at CalArts. At the time I was working for Richard Telles (who eventually opened his own LA gallery) at Roy Boyd Gallery in Santa Monica, and helped to facilitate Simmons’ debut exhibition there. The works presented in that and subsequent exhibitions were centered around issues of education and race. Even early on in his career, he had a sophisticated conceptual and visual vocabulary.

Simmons’ exhibition “Screaming into the Ether” was scheduled to run March 26–April 25, 2020 at Metro Pictures in New York, opening just as everything shut down. It remained on view in the closed gallery until recently, seen only by appointment. (The exhibition was extended through Sept. 12.) We chatted by Zoom in August, discussing his recent exhibition at Metro Pictures, making work in Los Angeles as opposed to New York, painting, and his signature style of erasure, while touching on life and art during the pandemic.

Jody Zellen: How did it feel to have an exhibition on view during the pandemic, one that very few people could see? Did the gallery use social media and the web to promote the show?

Gary Simmons: I was very surprised because I’ve been with Metro for almost 30 years now, and they’re old school. They’re like old ’80s Pictures Generation: they open the doors and whoever comes, comes. They don’t pick up phones and do the phone crunch thing. Then suddenly this pandemic hits. They pivoted so fast and everything moved like lightning speed. Suddenly I was online; I was doing all of these interviews. I was talking to all these people. And they were moving the work. They started an online-film series—they were one of the first to do that. They asked me to create a playlist. They wanted to create an active online-viewing experience for the exhibition. When they finally opened up, a ton of people were so hungry to go out and see art that they just packed the gallery to see it. Financially, it did really well. Critically, it did even better.

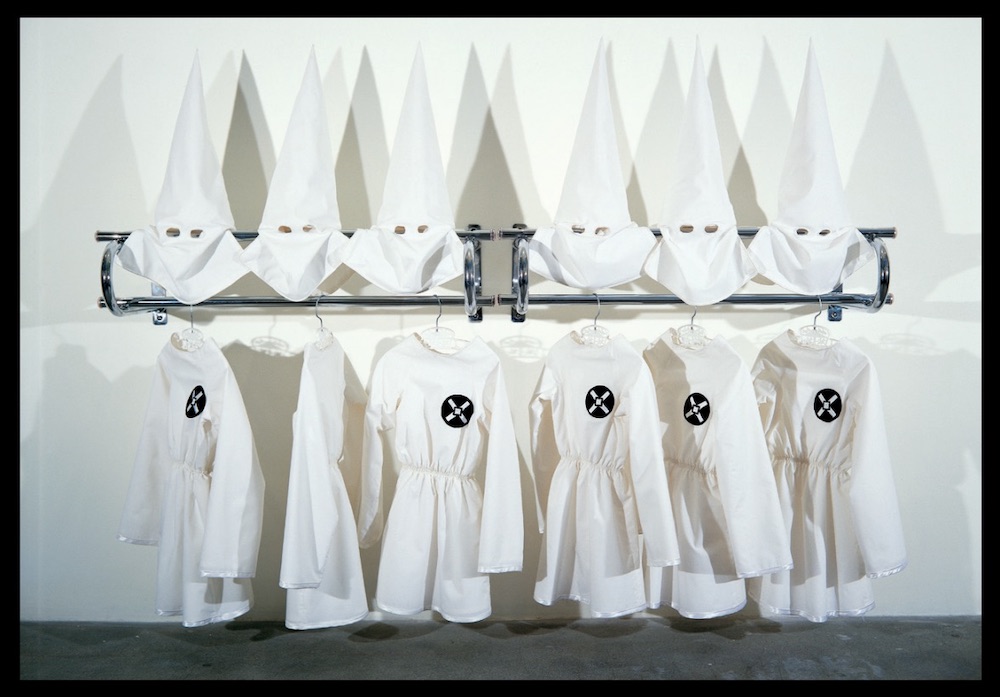

Us & Them (Robes),1991, ©Gary Simmons, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

What are you working on now?

Usually right after a show, I take time off anyway, it’s like trying to recharge the battery on your computer. I just need a couple of months to plug in and get the jets moving again. So in a weird way, this has been a time for me to sit back and absorb. It’s

super-hot right now, so I only go to the studio in dribs and drabs, but I’m starting to get back into it.

Throughout your 30-plus-year career you have spent time both in Los Angeles and New York. Can you speak about the differences in being an artist and making work here in LA versus in NYC?

You know, I always have had this kind of love/hate relationship with Los Angeles. And I think this time it’s total love. I think one of the things is that it’s a horizontal city, not only in the literalness of the sprawl, but also the way you think about your work has more of a side-to-side kind of application to it. New York is about compression and pressure. Everything is more vertical, your space is smaller, you’re limited in scale and how you approach and make your work. LA allows for a lot of space—literally, for me to make the work—so I don’t feel as if there’s anything I can’t make out here, and not having those limits is really great. The art world has really changed; it has shifted. New York isn’t the center of the world like it used to be. There’s a lot of things about LA that are more like the ’70s and ’80s growing up in New York. There’s more mom and pops, there’s more opportunity to start a new business. There are more things to find to make art on some levels.

Six-X, 1989, ©Gary Simmons, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

How does the early work you first showed at Roy Boyd Gallery relate to what you’re making now?

I was looking at some of that old Roy Boyd work which pops up here and there. Some of it was in a show last year at the Walker. They called me up and said, “Hey, how do you feel about the robe and towel pieces like Us & Them (1990), Us & Them (robes) (1991), and the boxing gloves piece, Everforward…(Neverback) (1993). How do they relate to the current social justice thing that’s going on?” We talked about how these pieces felt just as fresh, sadly, as they did then. They are just as relevant now.

I remember the impact of Six-X (1989). Maybe you were ahead of the times and now the times are catching up. Can you talk about erasure, something that has become your signature style?

That sense of carving out your own sort of marks that are identified to you, that’s something that I am actually really proud of. So I continue to work with that [erasure] because it’s something that took a while to develop.

Installation view of Balcony Seating Only at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, November 11 – December 22, 2017. Photo: Brian Forrest, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

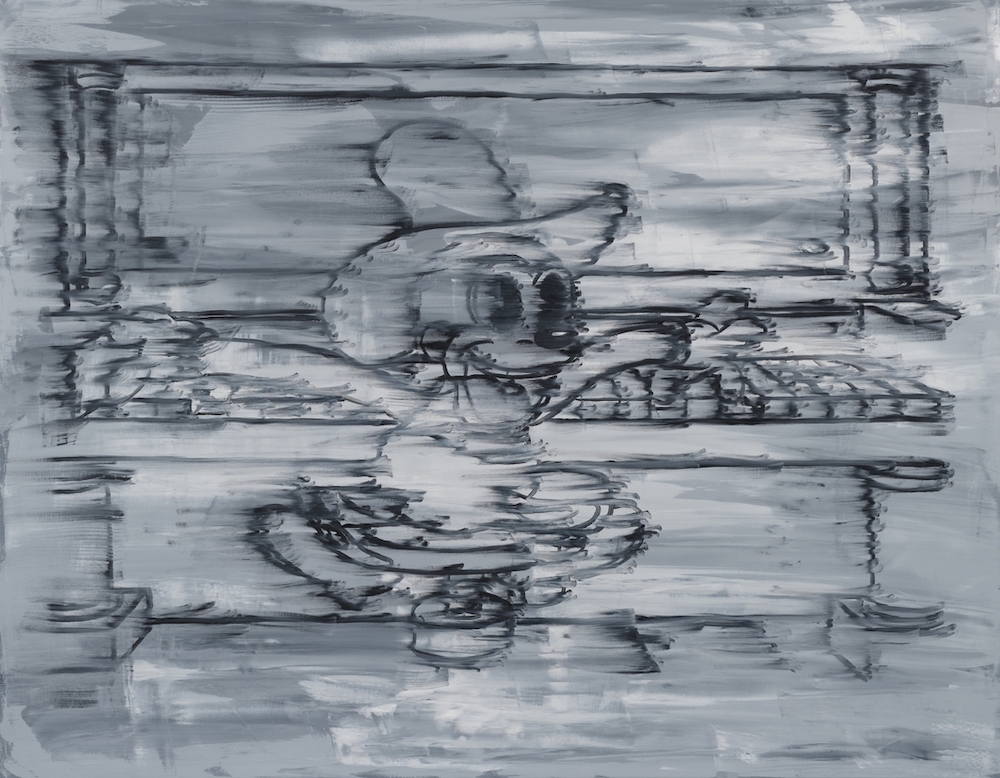

You’ve created erased works depicting cartoon characters as well as text. The 2018 show at the California African American Museum was text, based on film titles, and in the 2013 show at Regen Projects the paintings were covered with the names of African American actors, while the show at Metro Pictures was a return to the cartoon characters you began drawing in the 1990s. Can you talk a bit about text vs image?

Film has always been a big starting point for me. In these works I make the language physical, like an image. This recent series is about going back to cartoons, using motion pictures and movement and blurring and the physicality of me embracing this. I am interested in the remnants that are left behind, those traces, those ghosts.

For the CAAM show, I really wanted to work with the notion of silent film and bringing some of those people and those films back to the surface. I love to mine territories that are forgotten. A lot of those film titles and the Black actors and actresses that were in those films are long forgotten, yet still have a place in history. We’ve somehow erased them and I wanted to bring them back. The same goes for the cartoons. The thing about the cartoons that made me start to work with them again was like—these are my guys. They are like old friends.