In the rehearsed simplicity of “CLOSE, not too close” at David Zwirner, artist Rose Wylie grapples with Platonic ideals and the basic tools of semiotics. In both work on paper and oil on canvas, the artist depicts, again and again, important personal symbols. Repeated, for instance, is her pared-down home—a sheltering structure constructed of twelve lines encompassing ten squares—as well as her least embellished rendering of Selling Sunset’s Christine Quinn—a dark hourglass flanked on one end by two toothpicks and an oval with yellow drapery on the other. Going from the drawings to the paintings, one sees Wylie’s deceptively simple subjects, and the phrases emblazoned upon them, recur and recur, simplifying in each iteration to absorb more meaning.

Rose Wylie, White Building, 2022. © Rose Wylie. Photo: Jack Hems. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.

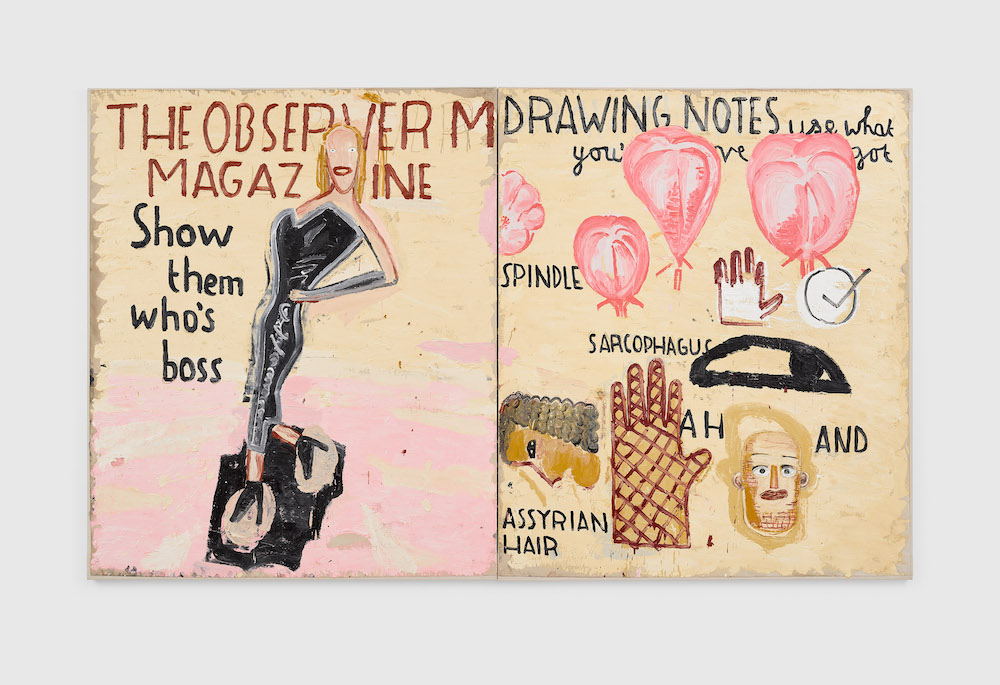

Inventing her own picture-based language—one thinks of shorthand or hieroglyphs—Wylie toys around with the denotation of each image, changing it or pairing it with different words across separate works. HAND, Drawing as Central (2022) demystifies this visual code development within a single tryptic. The panel labeled “THE PAINTING” contains only the word “hand” and the likeness of a large hand rendered in black and white and wearing a sizable wedding ring. “THE DRAWING,” in contrast and as the presumed earliest step of the three, contains all the information that the hand in the painting will later absorb—it’s completed in full color; it plays around with shadows and the word “SHADOW”; arrows imply motion that it would make across a substrate’s surface. “THE OIL ON PAPER” is compositionally like the painting, but much smaller and it has some smudging that is later excluded; Wylie is extremely intentional with the sparse nature of her works.

In the writing process of an essay, one might first take notes, from those notes produce a draft that will go through several edits, and, finally, form a very polished copy to go to print in the hopes that it contains the most intentional use of language components possible—that it might bridge understanding impactfully. As Wylie illustrates, this procedure crosses disciplines in similar forms. However, rather than build her paintings bigger than her studies—like an essayist to their notes or Michelangelo drawing as a mode of investigation for his paintings—Wylie draws with a great deal of noise that she later trims down in her paintings—much like a poet wondering how few words a poem might be. Where some painters are busy composing the equivalent of a novel, filling their canvas with mark upon mark, gesture upon gesture, trompe l’oeil, or any multitude of painterly techniques, Wylie cuts the fat like the concrete poets—imagine Aram Saroyan’s lighght—reaching through the murkiness of relatability with a carefully cultivated, select few signifiers.

0 Comments