Peter Hujar’s square format black-and-white photographs are a reminder of the beauty of film and the power of a well-composed, carefully lit, and patiently observed image. Hujar died of AIDS in 1987 at the age of 44 and left behind an exceptional body of work that includes self-portraits, portraits, photographs of animals, as well as city scapes. No matter what subject was in front of his lens, he framed it with the same degree of respect and sensitivity: a photograph of a goose or two cows has the same impact as a portrait of, for example, Susan Sontag or Divine.

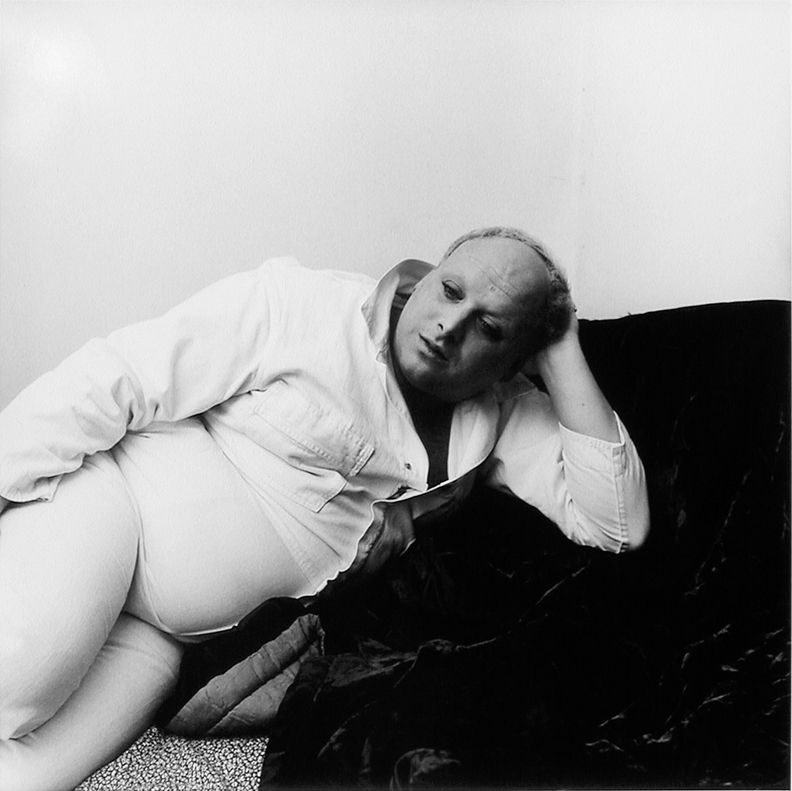

Peter Hujar, Divine, (1975). 20″x16.” Courtesy of Marc Selwyn Fine Art.

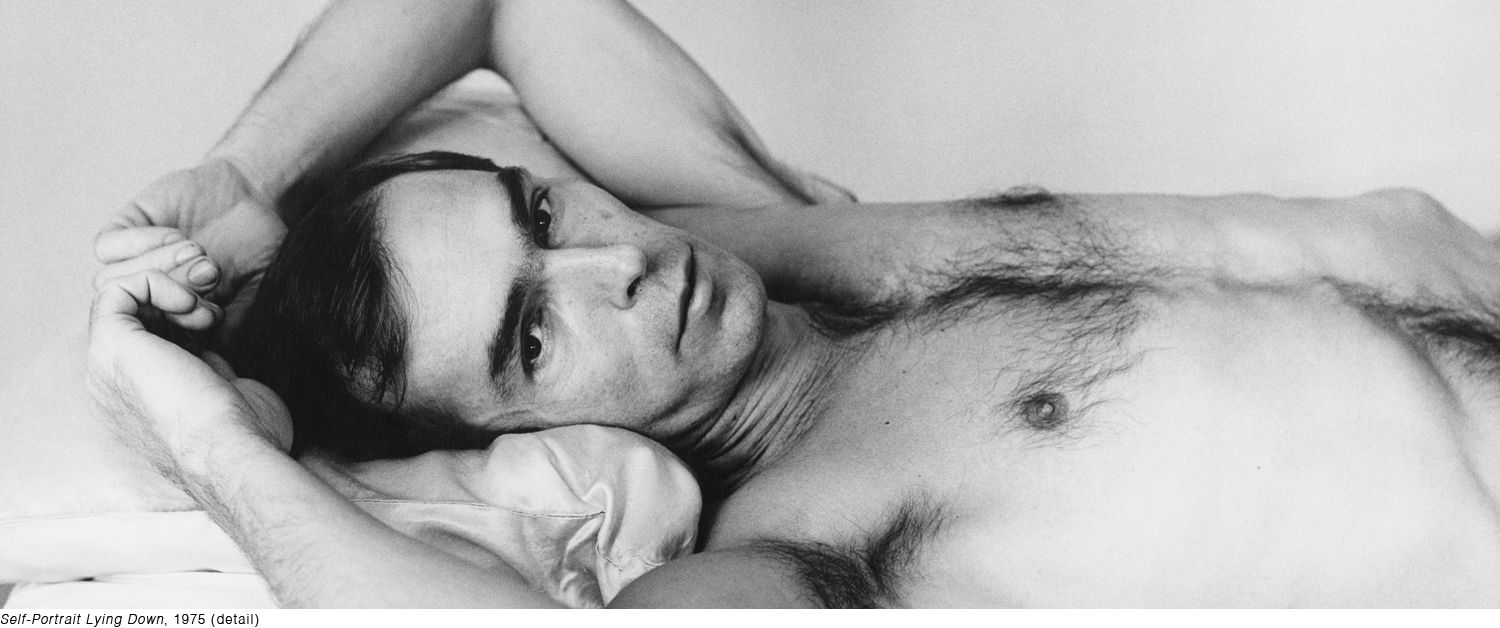

Hujar’s compassion toward his subjects — whether human or animal, animate or inanimate — was unique and the people (or animals) in his images display not only vulnerability, but also a sense of trust. In Divine (1975/2020), Hujar captures the man casually dressed, reclining on a lush black throw. Divine seems relaxed, neither performing nor in costume. He pensively and thoughtfully gazes down, surprisingly not at the camera or out of the frame. The fabric that surrounds Divine is beautifully lit, its rich black-and-gray tones contrasting with Divine’s white clothing and the light gray wall that tops the composition. A similar air pervades in David Wojnarowicz, 1981, a portrait of the artist in repose staring off into the distance. Wojnarowicz (who also died of AIDS in the 1980s) is shirtless and depicted relaxing against a rumpled pillow and folded sheet, at ease within Hujar’s viewfinder.

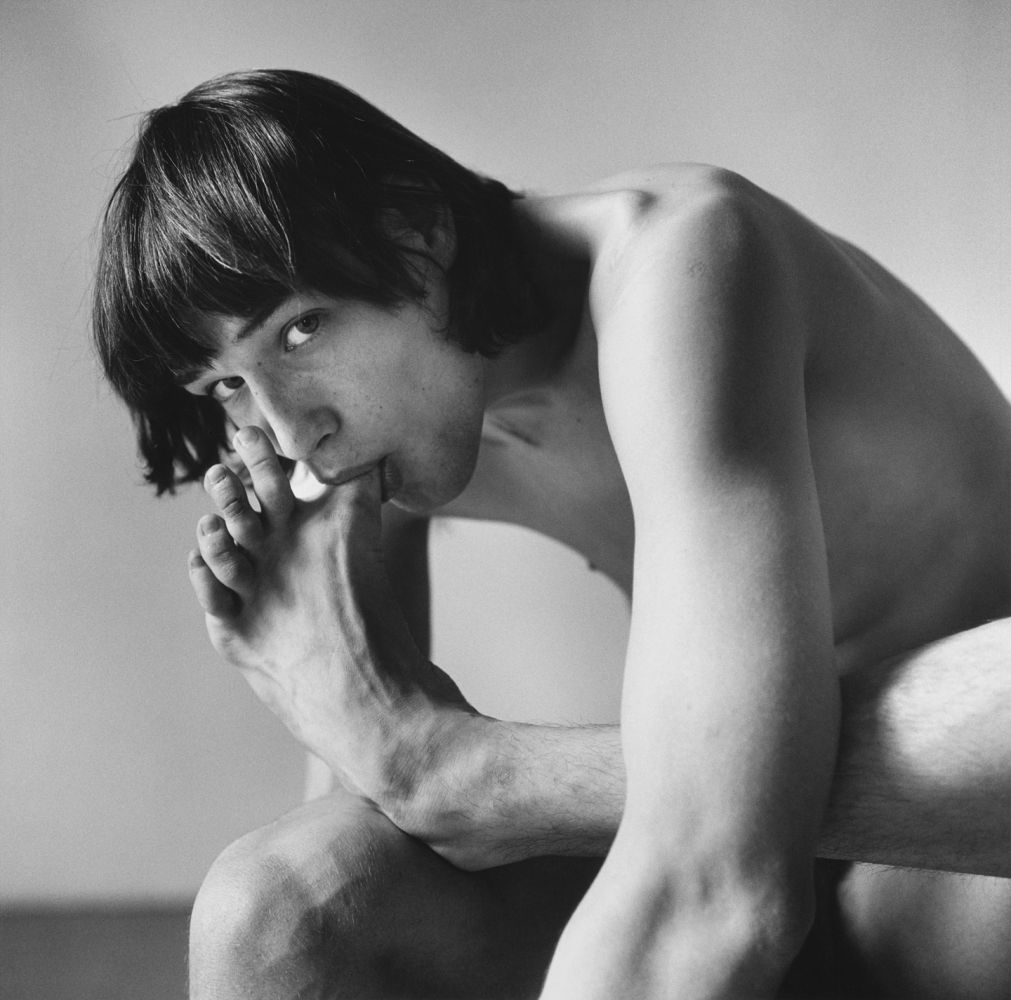

In Daniel Schook Sucking Toe (Close Up), 1981 Hujar delights in the angled geometry of the subject’s nude body as he leans over to suck his big toe. Similarly, in Gary Schneider in Contortion, 1979/2020, Hujar celebrates the body’s ability to bend in unusual ways, photographing Schneider’s muscular and twisted body from the back as he places his leg behind his arm and over his head. The shape of Schneider’s backside and the subtlety of the folds and tonalities of his skin brings to mind Edward Weston’s iconic photograph of a pepper.

Peter Hujar, Daniel Schook Sucking Toe (Close-Up), (1981). 20″x16.” Courtesy of Marc Selwyn Fine Art.

Thoughtfully installed with a mixture of images, the exhibition implies a narrative that proclaims — “this is where I live, these are the people I associate with, this is where I go and this is what I see when I am there” — as viewers move from portraits to cityscapes, to images of undulating ripples in the Hudson River. In Butch and Buster, (1978/2020) two cows stare out from the center of the photograph. The texture of their matted fur is echoed by the trees behind them as well as the grass upon which they stand. Each cow displays a distinct personality and neither seems bothered by Hujar’s presence. When framed in his lens, be it person, place, or animal, each subject is presented with integrity and compassion. Though the settings are often barren —just a white wall and concrete studio floor with few props or decorations— Hujar allows his sitters to fill the frame both literally and metaphorically.

Often paired with Diane Arbus and Robert Mapplethorpe, Hujar was not interested in sensationalism or that which was out of the ordinary; rather he was concerned with the essence of the person and what was implied or inferred by the portrait. A master craftsman, his black and white, precisely framed pictures are lush and sensual, each fold of fabric, swish of hair or pensive gaze, the perfect shade of gray. While the images on view represent a fraction of his output, they attest to his mastery of the photographic medium and to the tragedy of a career and life cut short.

Peter Hujar

Marc Selwyn Fine Art

November 14, 2020 – January 9, 2021