An avowed pacifist and activist, Pedro Reyes is known for his sculptures that subvert the potential violence of guns by transforming them into shovels for planting trees or musical instruments played in performance. In his current exhibition of recent sculptures and works on paper, his political intentions are a bit more subtle. Relying upon his knowledge of Pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican codices and the history of modern art, Reyes appears to be searching for a simple, symbolic language for championing peace and humanistic values that is rooted in his Mexican heritage, yet universal in its appeal and comprehensibility. Accordingly, many of the shapes employed in the new works derive from pictographs found in the ancient codices, while 20th-century influences include sculptors Constantin Brancusi, Isamu Noguchi, and Henry Moore, and painter Adolph Gottlieb— artists who believed in abstraction as a stylistic vehicle for reducing something to its essence or for representing higher truths.

One way Reyes’ shows respect for cultural history is through his titles, most of which are in Spanish or Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. His sculptural mediums now include volcanic stone, which is available in a variety of colors, as well as marble and jadeite, the principal mineral in jade. Because these materials are from the earth and have been around for eons, Reyes believes they metaphorically embody the history of humankind, and are thus well suited for works that celebrate humanity’s endurance and survival. All of the sculptures are hand carved by a collaborative team of workers, thereby providing essential employment for skilled laborers at a time when people are being replaced by robots and artificial intelligence.

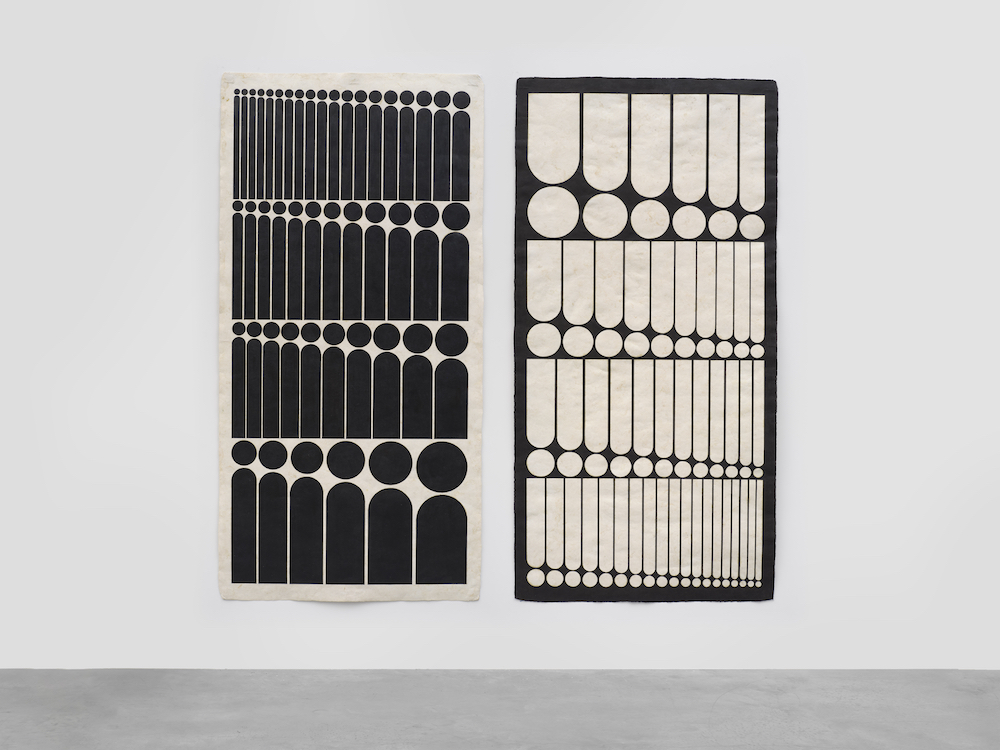

Pedro Reyes, Tlapicalli, 2021. © Pedro Reyes, courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Among the most powerful works in the exhibition is a totemic abstract sculpture that resembles an obelisk or column. Built by stacking rectangular and cylindrical blocks of red tezontle stone that resemble bricks, each section of Tlapacalli (2021) is configured in a variation of the Pre-Columbian pictograph for a house. While recalling the geometry of Mesoamerican architecture, the sculpture also reminds us that the security of a good home is something that has enriched human lives for centuries and is universally desired. Yet, like any ideal, it is not always attainable. This latter idea is reflected in the visual precariousness of the structure. Although it is stabilized internally by concealed metal rods, the individual building blocks are not perfectly aligned, thus it deceptively seems as if it might topple.

As an alternative strategy, Reyes carved several semi-abstract figurative sculptures in the shapes of widely familiar emblems for peace: two clasped hands, a dove with an outstretched hand for a tail, and a circle of embracing friends. In terms of communicating with viewers, this approach is simpler, more direct, and more immediately accessible.

For the paper works, where pictographic imagery also abounds, Reyes prefers amate paper, which is essentially tree bark smashed with stones and was used in creating the ancient codices. In the diptych Signos (2023), a delightful musing on the duality of the yin-yang principle, Reyes exposes both his serious and playful sides. In the left panel, black Spanish (upside down) exclamation points are arranged in registers on a white field; in the companion panel, they are shown the same way in English (right-side up), and painted in white on a black field. The height and width of the exclamation points are varied across each row such that an energetic movement emerges, a life force of sorts that reinforces the notion that they really caricature people of different body types existing in a world of harmonious coexistence. As in his sculptures, the message here is that if we are to attain lasting peace, we must first achieve communal balance and equality.