“Groove,” an exhibition of approximately 100 intaglio prints currently on view at the Hammer Museum, has something for everyone, and a bit of everything (save for works in other media), but it will appeal most to those with an unrestricted appetite for aesthetic pleasures. Drawn from the collection of UCLA’s Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, the exhibition displays the gamut of techniques used by artists across the last five centuries to incise their printing plates and confirms the miraculous alchemy of these procedures.

From the point of a needle, from the bite of acid and spit, entire worlds appear. They spring forth in an instant, concealing interminable hours of concentration and effort. Images produced through engraving and aquatint likewise gloss over the coats of resin, sugar, and wax the artists applied to rein in their chemical assistants, before wiping them away. The outlines of metal plates girding many of the pictures index the invisible force of etching presses which transferred meticulously defined channels and washes of pigment to dampened paper. Pressure, as a prerequisite for printmaking, takes center stage in Willie Cole’s Five Beauties Rising (2012). Inked with repurposed and expressionistically distressed ironing boards, Cole’s suite commemorates the tools used by his family members—who worked as housekeepers—to press clothing, translating their unseen, undervalued and grueling labor to a visual medium, and moreover, to a vertical format that is consonant with the reverential genre of portraiture.

Despite intaglio’s status as an ancillary fine art medium (ranked lower for turning out editions rather than ‘unique’ originals), “Groove” provides a fortuitous survey of Western art history, recording assorted shifts in style, subject matter and composition that have taken place since the Renaissance, as well as the slowly broadening range of identities to receive institutional recognition and representation. The survey commences with capacious, 16th century etchings by Albrecht Dürer, Pieter van der Heyden and Giorgio Ghisi that are replete with angels, creatures, inscriptions and overlapping allegories, as well as unexpected variations in scale that somehow do not disrupt the overall verisimilitude of these tableaux.

Artists working in the 19th and 20th centuries (all of whom are European), engage a democratizing approach: everyone and everything is potentially a subject, including proletarians and banal landscapes. See, for example, Albert Besnard’s Morphinomanes, ou Le Plumet (1887), a sidelong snapshot of two women seated at a café table so saturated with opium smoke that the rear figure appears to be evaporating into the background. Prints become altogether less populated as the exhibition progresses (clockwise around a single gallery) through impressionism, expressionism, and abstraction. We arrive at a neat, predictable apotheosis with Robert Therrien’s minimalist composition No Title (Dutch Door) (1996), which shows two ruby red, irregular quadrilaterals, floating kitty-corner to one another in white space.

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514. UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum.

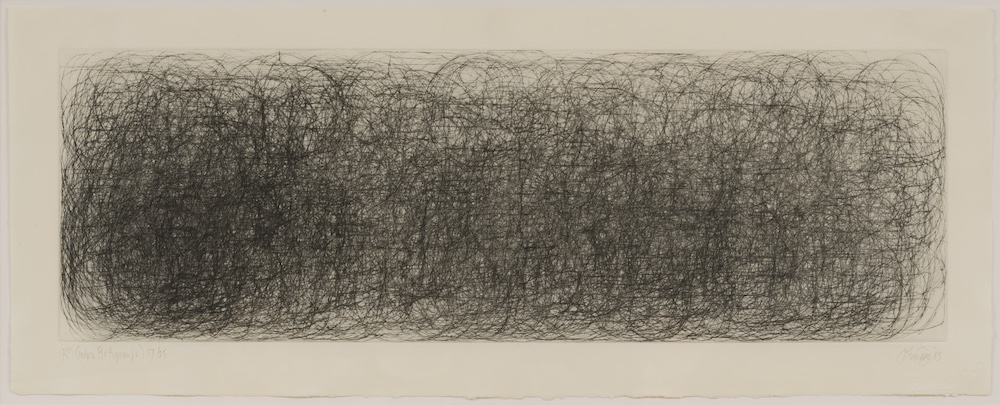

“Groove” is worth seeing if only to witness the different uses artists have made of a hard line across the ages. In Melencolia I (1514)—the oldest and most masterful work in the show—Dürer crafts each mark to enhance the shape and texture of the subject it represents. The lines depicting the fur of a sleeping dog bristle outwards, while those describing the contours of a wooden hand plane bow and curve. Compare this to John Cage’s R3 (Where R=Ryoaniji) (1983), a gaseous cloud of overlapping arcs that evinces nothing but the sloping, scraping gait of the artist’s hand.

Two astonishing feats of trompe-l’œil, created 300 years apart, testify to abiding obsessions with illusionism and technical cleverness. Many visitors drop their jaw when they read the wall text and discover that Claude Mellan’s The Sudarium of Saint Veronica (1649) is printed from a single, spiraling line etched at varying depths and widths to describe not simply the face of Jesus bearing the crown of thorns, but the cloth that was imprinted with his likeness, when—prior to the crucifixion—Veronica wiped away his sweat and blood. Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s Paint Under Tape/Paint Over Paper (1977) is more subtle, but likewise operates as a visual earworm. By using the approximate science of aquatint to modify tones of green, ocher, pink, and umber ink, and rendering more precise outlines with an etching needle, Mangold conjures a perforated sheet of vintage drafting paper affixed to a white ‘support’ by four worn strips of yellow painter’s tape. In fact, however, this blank ‘support’ is the real paper fiber to which Mangold’s guileful ink is clinging, and aping paper and tape. Once you take in Mangold’s masterclass in mimesis you won’t easily get it out of your head. “How did she do that?” you might think, while waiting for a light to change.

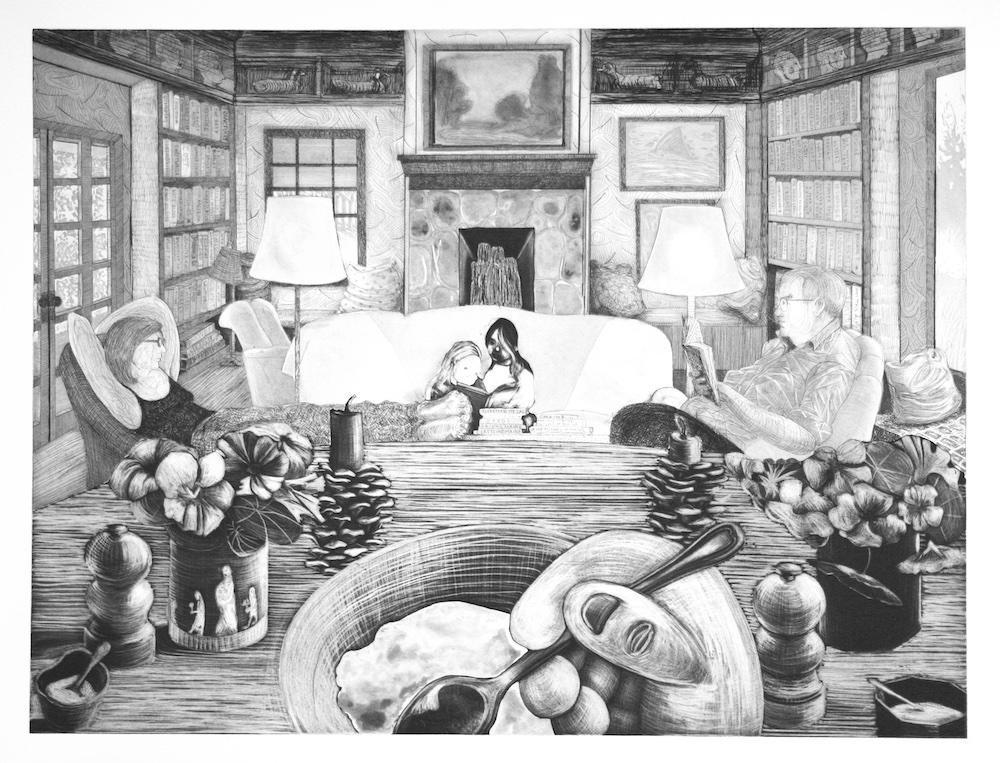

Nicole Eisenman, Watermark, 2012. UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum. Purchased with funds provided by the Marcia Weisman Endowment Fund. © Nicole Eisenman. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Although the layout doesn’t guarantee it, a walk through “Groove” might conclude at a short, peninsular wall bearing three prints by Nicole Eisenman, all dated 2012. On the left-hand side, in Twelve Heads, a dozen discrete portraits are arrayed in a three-by-four grid on a single surface. Varying slightly in size, they espouse the sort of stylistic polyglotism that I associate with Picasso: in one, Eisenman deploys a sophisticated combination of etching and aquatint to sketch out a youthful figure in repose; others are cuboid or neo-expressionist, sparsely constructed from broad lines.

Eisenman’s best tricks are, however, compositional, as evidenced by Midnight Wander and Watermark. With the former, she plops us into a computer monitor, from which we peer out at a dozy woman ensnared by the serotonin drip feed of the internet: the “wanderer” lazily watches us, just as we examine the free-spirited network of lines that trace her bulbous features. In Watermark, we’re suddenly animated, spooning oatmeal or yogurt to our lips as we pass a leisurely morning with an upper-middle-class family in a summer cabin. By emphasizing the picture plane as a window, and situating our viewpoint within a larger world that can only be inferred from her delimited scenes, Eisenman heightens our awareness of the image as a form of fiction that we are eager to co-construct and participate in. After 500 years of looking, it’s a boon to receive the reminder.