If—in the next couple days—you are keen on communing privately with melancholic beauty (or “tough joy,” as the artist might have it), visit Christopher Culver’s latest suite of charcoal and pastel drawings on paper at Michael Benevento Gallery. Never mind the building’s ashen façade and foreboding electric gate. Behind its metal fire door, you’ll find four brightly illuminated galleries that facilitate all-consuming encounters with a sparse sequence of dreamlike images.

Though the surfaces of his pictures are too brindled with infinitesimal, varicolored streaks to be called hyperreal, Culver’s compositions are exceedingly precise. Like liquid, they maintain a constant volume, running from border to border on papers of various sizes. In several drawings, Culver has worked up to a single raw or torn fringe that contrasts starkly with the other three cut edges of the sheet, intimating a brim from which the scene could spill over.

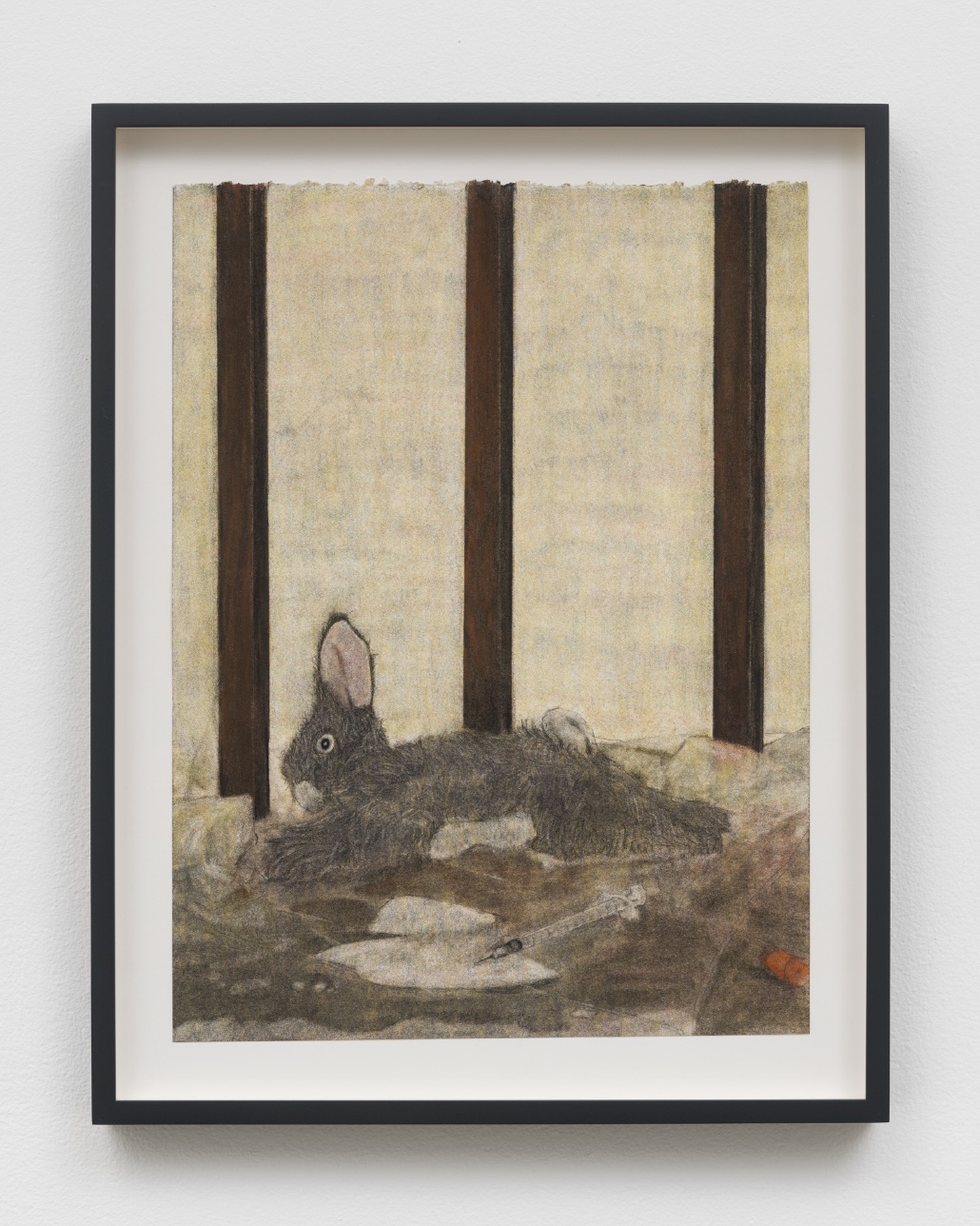

Discrete compositional strategies are deployed across a number of works. In Strange Neighborhood and Let Me Hold You For Awhile (all works 2024), Culver bisects broad, horizontal picture planes with rusty vertical bars, rendering richly textured portraits of canines behind them. The bars appear again in the background of Needle on the Ground, implying that the viewer has entered the cage, where we are confronted by a jarring array of figures. These include a prone rabbit, white scraps that resemble tissue paper, and an orange-capped insulin syringe (a type of needle that is favored, due to its small bore, for the intravenous injection of drugs).

Christopher Culver, Needle on the Ground, 2024.

Culver’s bunny—a repeated motif throughout his broader oeuvre—emits an aura of indeterminacy. Is it a stuffed toy, or is it ‘real?’ Is it resting, or is it dead? Here, it may be rewarding to recall The Velveteen Rabbit, a narrative that considers the animating psychic force that humans apply to mimetic objects. Culver conjures two more explicitly intertextual pictures with To be Back in the Desert Again and There’s more to life than a little money, you know… Don’t you know that? Exploiting airplane seatback screens as framing devices, the ghostly central images in these works are borrowed from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Fargo, respectively.

Without a checklist, Culver’s compositions might be hard to pin down as drawings. His blended skeins of pastel achieve effects that are more often generated by skillful underpainting. Threadlike lines of charcoal—which do much to define the structures in his scenes—recall the fixed architectures of engraving prints. With San Francisco Sunset, Culver flexes his talent for objectivity, capturing the warm glow of late-afternoon sunshine as it illuminates a semi-transparent, blue laundry hamper, a makeshift bed, and a bank of windows, casting the skewed shadow of its grid of frames across the interior walls of an apartment.

Ironically, Culver’s showstopper succeeds in spite, or perhaps, because of a lack of proportionality. Cutely titled, Car Jerk shows a figure with a condensed torso and an oversized left arm receiving a vaguely unusual sexual favor from a partner leaning into the vehicle from outside the passenger door. In addition to being subtly Mannerist, the image is strangely hagiographic, echoing a pietà. If the figure were to rise and remove the pillowcase concealing their identity, I’d wager that their likeness would be imprinted on the shroud—just as the shape of their penis is legible beneath their tighty-whities.