The people depicted in Ally Rae Peeples’ exhibition “Crowd Surfing” resemble how they might see themselves while on hallucinogens or in a house of mirrors, where bodies become distorted, facial expressions are exaggerated, and distinctions between figure and ground are blurred within a seemingly warped space. For Peeples, who watched her sister perform in amusement parks as a child, such imagery is perfectly suited to exploring the difficulties of connecting with others in the digital age, where interpersonal relationships are increasingly obstructed or replaced by inordinate amounts of time spent with computers and cell phones. Ironically, such technological devices play a key role in the development of Peeples’ imagery. Although her large-scale oil paintings are painted freehand, they are based on digitally developed compositions. Each crowd scene, in fact, derives from a stock photo mined on the Internet and then manipulated using the photo editing apps Procreate and Facetune. Once satisfied with a result, Peeples works from the imagery displayed on her iPad, but makes changes and enhancements in an intuitive manner while painting.

Overall, Peeples’ paintings are disconcerting in the best sense of the term. With most of the figures so tightly packed into claustrophobic spaces that permit little breathing space, these works convey uneasiness about our current zeitgeist. Many of the figures, in fact, are shown approaching the viewer, as if they are to invade our space like the ghouls in the classic cult movie “Night of the Living Dead.” The four individuals whose faces merge as if melting in The People Watchers (2023) are presented in panoramic close-up, as if we are seeing them on a movie screen. While they appear to be of differing ages and genders, three of them stare at us with questioning gazes that contrast with the less intense and more inward expression of the fourth.

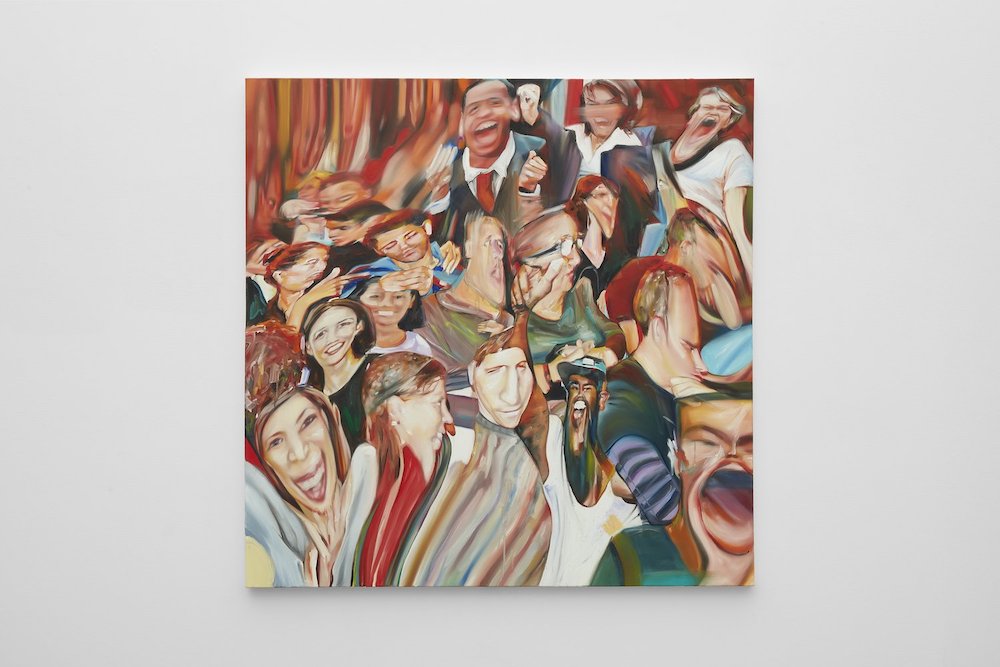

Ally Rae Peeples, Social Suicide, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Lowell Ryan Projects. Photo: Evan Walsh.

In The Dance Recital (2023), an interracial crowd of men and women expresses mostly joyful emotions, as reflected in their exaggerated smiles and screams. Perhaps they are responding to music, as suggested in the painting’s title, but who they really are could be masked by the facades they display while caught up in a moment of frenzy. A different sort of crowd mania is at play in Social Suicide (2023), where everyone gazes upward while seemingly under the spell of a Christ-like cult figure who, with outstretched arms, appears to be their supposed savior and puppeteer. While the crowds in both paintings recall the parading partygoers in James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888; Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum), Social Suicide is especially relevant as a timely caricature of the present-day MAGA movement.

Other themes addressed in Peeples’ paintings include the harmful effects of climate change on sunbathers and the alienation of pedestrians who fail to acknowledge others who pass them by. The compositional dynamism of people walking in the same space but in different directions, seen in Peeples’ Corporate Godzillas (2023), is comparable to similar effects in the pre-World War I Berlin street scenes by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) and the 1980s paintings of Manhattan pedestrians by Robert Birmelin (b. 1933). Although Peeples uses new technologies that were unavailable to these predecessors, she also demonstrates that some things never change.