Among the amateur photographers of our time are some rare daguerreotype buffs who still practice this 19th-century form of portraiture, which creates a unique image on a photosensitized metal plate. Back in the 1990s, two such buffs were shrewd enough to realize that an auction house specializing in gun sales didn’t know what they had when they listed as a miscellaneous item a box of odds and that included some “old-time” photographs. What the gun nuts didn’t realize they had were two

daguerreotypes; one of Kansas abolitionist John Brown, the other of the liberated slave Frederick Douglass.

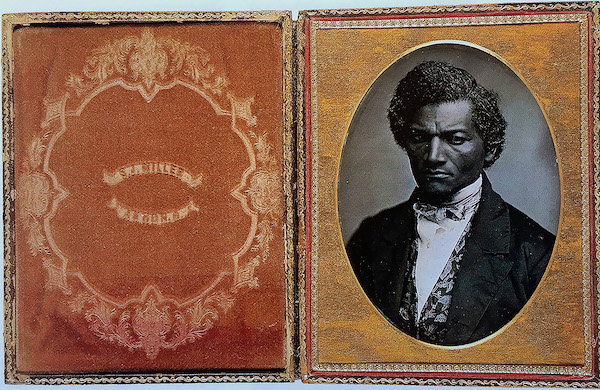

It was my good luck in the 1990s as a curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago to bid at an auction on the Frederick Douglass portrait and acquire it for the museum. It is, I feel, the greatest portrait ever made of Douglass.

That’s a big claim because after Douglass escaped in 1838 from the slavery into which he had been born on a Maryland plantation, he became an icon of the Abolition movement in the North. He was the embodiment of the Abolitionist cause with extraordinary looks matching his extraordinary talent as a lecturer and writer championing that cause. He also published two newspapers in support of Abolition, and his prominence as a spokesman earned him two meetings with Abraham Lincoln at the White House before the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Douglass had to escape America altogether, ending up for a time in Ireland, to keep from being dragooned under the Fugitive Slave Act and returned to his enslaver in Maryland. He was able to come back only after his champions in the North raised the money to buy his freedom from enslavement. Once freed, he traveled relentlessly for the Abolitionist cause. Ohio was a favored stomping ground because it was an important stop on the Underground Railroad where enslaved people were smuggled out of the South. Sometimes, when there was a local daguerrean portrait studio in one of the many little towns he passed through, Douglass would have a portrait or two made, leaving one behind as an advertisement for his cause. The extraordinary portrait of him you see here may have been created in just such a circumstance.