Over the past three decades, Fred Wilson has frequently exhibited objects in unexpected juxtapositions as a means for examining things in a new light. For his groundbreaking 1992 installation, “Mining the Museum,” he selected racially biased items from the collection of the Maryland Historical Society and presented them together—a strategy that called attention to historical omissions and misrepresentations of Black Americans. In this exhibition, organized to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his participation in the Venice Biennale, Wilson juxtaposes several of his previous sculptures—made of Venetian Murano glass—with works from other projects.

Wilson’s signature glass sculptures, the first in this style to be fabricated in the color black in Venice, include working chandeliers, wall reliefs and blown-glass “drip” sculptures. The chandeliers and mirror reliefs, essentially black-hued versions of the city’s flamboyant decorative objects, are especially ornate. As instruments for probing the layered meanings of “blackness,” these two bodies of works are based on Shakespeare’s Othello, in which the lead character, a Moorish military commander in the Venetian army, weds the noblewoman Desdemona—with ultimately disastrous results.

Fred Wilson, Bat, 2009. © Fred Wilson. Courtesy of PACE Gallery.

While the black chandeliers (there are also white ones) feel funereal, it is in mirror reliefs such as Bat (2009) that Wilson most forcefully expresses the horror that we might associate with the “Black Death,” the bubonic plague pandemic that devastated Venice in 1348, as well as with the atrocities that African Americans have faced over the centuries. With the oval shape of the frontmost mirror suggesting a wide open mouth, we can almost hear the spread-winged bat’s scream, an expression that has art-historical parallels in iconic works by Caravaggio and Munch. By contrast, Wilson’s black glass teardrops, which cascade down the wall in Dead End (2023), are distinctly minimal and exquisitely lyrical. Conceptually, he relates them to droplets of tar (as in “tar baby”), ink (used for signing away the rights of slaves) and oil (the toxicity of which adversely impacts low-income Black communities). He also connects them to the sadness he experienced as a child, when he was ostracized as the only African American at his elementary school.

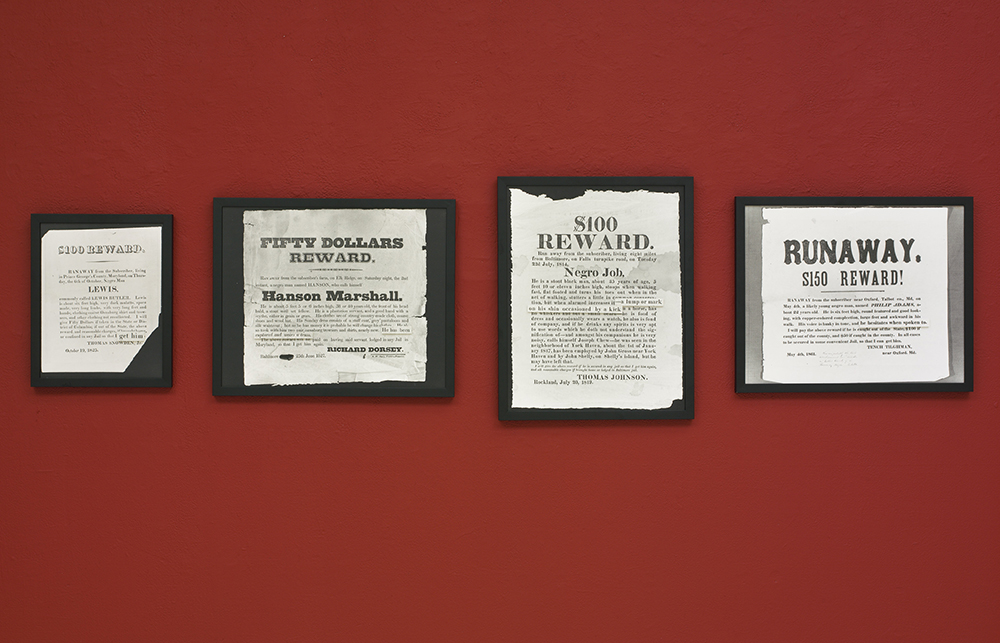

As revealed in a separate section of the exhibition, themes of slavery and death have been prevalent throughout Wilson’s oeuvre. Examples include framed broadsides advertising rewards for runaway slaves from “Mining the Museum” and a bronze-cast replica of a 1904 sculpture of an enslaved man from the Congo who was put on public display and subsequently committed suicide. Here, Wilson has cleverly wrapped a white silk scarf around the sculpture’s base as a dual reference to a KKK uniform and a noose. A sense of loss and mourning over injustices to African Americans is also deeply affecting, yet beautifully understated in two sculptures that resemble sarcophagi. Peering through the black glass of their exteriors, albeit with some difficulty, viewers will discern inkwells and oil cans, accompanied in one of the sculptures by a resin skeleton, a solemn reminder of both historical lynchings and the senseless murders that continue to this day.