“The aim of the dreamer…is merely to go on dreaming and not to be molested by the world… But the aims of life are antithetical to those of the dreamer, and the teeth of the world are sharp.”

This quote from James Baldwin’s 1962 novel Another Country is on the wall of Fred Wilson’s exhibition “Afro Kismet,” where its interpretation is left open. One might expect the artist to identify with the dreamer because of his deeply researched practice into museum collections and the social, economic, political and historical knowledge that illuminates objects beyond the mere cursory glance.

But Wilson’s research aims to dispel illusions. For more than 30 years, he has deconstructed museum collections to address issues of representation and the erasure of people of African descent from the histories presented within those collections.

“Afro Kismet,” originally exhibited in the 2017 Istanbul Biennial and subsequently at PACE in London and New York, now at Maccarone, examines the Venetian and Ottoman Empires, and the slave trade, as it trafficked Africans into Venice and Istanbul.

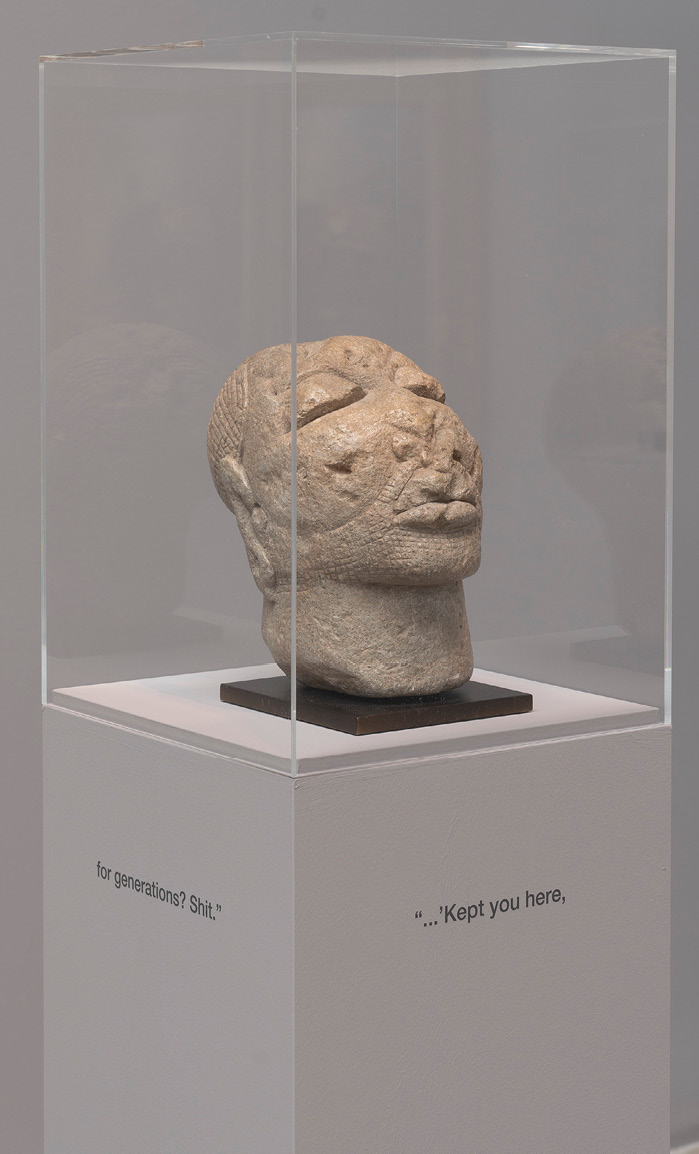

Fred Wilson, Not in a Hurry, Like From One Day to the Next, but, Every Day, Every Day, For Years, For Generations (2017), courtesy Maccarone.

Wilson draws from Baldwin’s novel, which the author wrote over an 11-year period while working in Istanbul, pairing excerpts as wall text with objects in the gallery. Another text, Shakespeare’s Othello, conceptually integrates “Afro Kismet” and a companion exhibition, titled “Glass Works,” of Wilson’s Murano glass mirrors, Venetian chandeliers and black Murano glass tear-drop shapes positioned as if seeping through and dripping along the gallery walls, or surfacing amid white structural glass laid flat on the floor. The underlying presence of Othello suffuses the exhibition with a meditation on literature’s power to create profoundly lasting impacts on culture, referencing representations of “blackness” as embedded from within a Eurocentric point of view.

Positioning objects from the Pera Museum (Istanbul) with other contemporary and fabricated objects invites reexamination. They Passed Their Lives Thereafter in a Kind of Limbo of Denied and Unexamined Pain (2017), an arrangement of engravings and an illustration of a scene from Othello implicates depictions of Afro Turks. Wilson covered the etchings with vellum, cutting out an ellipsoid to draw attention to each instance of a miniscule black figure in the distance, away from the central figures of the compositions. Other objects, like a stone Sherbro head are paired with text (…kept you here, 2018), evoking the displacement and enduring trauma of slavery.

In “Glass Works” Wilson again exposes racializing ideas by using lines from Othello as titles. One of these (A Moth of Peace, 2018), a white Murano glass Venetian chandelier, evokes an image of whiteness as a representation of the “purity” of Desdemona. It plays off the two Ottoman-styled black Murano glass chandeliers in “Afro Kismet” (The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark, 2017; Eclipse, 2017) and a black Murano glass mirror (I Saw Othello’s Visage In His Mind, 2013).

In these complementary exhibitions, Wilson reclaims object and narrative, calling attention to the ways the slave trade and the African diaspora permeate the histories of global trade and culture, yet have stubbornly been overlooked as if invisible.