Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Or not. Fred Lonidier’s recent show of photographic work provides a telling demonstration of two inextricably interconnected facts. First, that a vast cultural chasm has opened up between the present world and that of the early to mid-1970s, when the work on view was produced; and second, that the passage of time across that chasm has had a variable impact on Lonidier’s work.

During the period represented by the work on show, Lonidier was among those instrumental in establishing the theory and practice of what came to be known as conceptual photography, an achievement that earned him a spot in this year’s Whitney Biennial. Politically engaged, blurring the lines dividing documentary and art as well as fine art practice and pop cultural production, and often combining image and text, the show is introduced by a theoretical statement in the form of a single 11×20-inch black-and-white photograph, which records a famous text from Karl Marx’s 1843 A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and contains the (in)famous aphorism: “[Religion] is the opium of the people.” Systematically defaced, however, every occurrence of the words “religion” or “religious” has been crudely over-written with the term “ART.” Although perhaps an obvious conceptual gesture, the defaced text reveals the source of Londinier’s political engagement, and an interesting internal contradiction: on the one hand, the artist sees art as a critical political tool; on the other, he is drawn toward an identification of “ART” with the “halo” of that “veil of tears” which is subject to the same political critique.

Inside, the show presents four ambitious works from the period 1972–1976. Most problematic, the newly reconstituted “Girl Watcher Lens” of 1972 reads today as a moderately interesting study of the extent to which an image (for example, a photograph of breasts under a tight sweater) can be excerpted and still retain its visual legibility. Unfortunately, the context within which this exercise is presented (a real “girl watcher” [camera lens] available at a bargain price), makes it clear that something more was intended: an incipient critique of the objectification of women’s bodies, that, unfortunately, has not held up well.

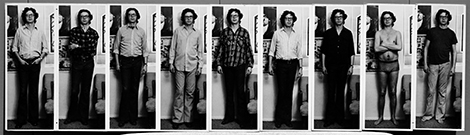

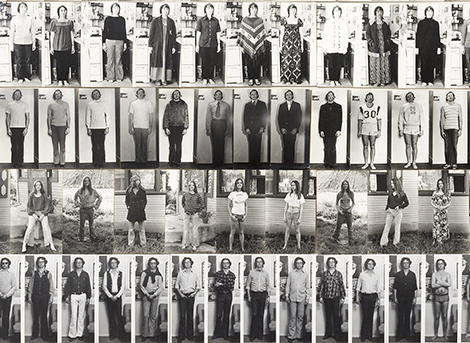

Much more successful are the intimate and poignant 1973 series “Two Girlfriends” and the complex conceptual Representations of Self-Representations (1973), essentially a collaboration between Lonidier and a group of students presented with a challenging self-portrait assignment. These works raise questions about identity, self-representation and the status of photographs as art and as documents that are, if anything, more pressing in this world awash in digital images and Facebook “selfies,” when everyone has a virtual darkroom in their cell phone. Representations also suggests Lonidier’s skill as a teacher, an added dimension to his social engagement.

Most closely related to work showing at the Whitney is the ambitious 1976 installation, “The Health and Safety Game (Edition 1).” Like his later work, it embodies Londinier’s long-standing commitment to workers’ rights; here the cost-benefit equations (the “game”) that pits workers’ health and safety against corporate profits. This is still a powerful, disturbing work; the photos are quite graphic, a brutal chronicle of personal pain and suffering; the bureaucratic texts can still enrage. But a lot has happened since 1976 (OSHA, the AIDS epidemic, Erin Brockovich, Obamacare), all of which gives Londinier’s work the look of something out of the “deep past.” Still—and despite the change—enough of “everything” remains so that “The Health and Safety Game” endures as an important work and fitting testament.