It was not by accident that the ‘hub’ of the 2014 FotoFocus biennial in Cincinnati was given over to Instagram, augmented by satellite displays throughout the city, including Cincinnati’s Memorial Hall and the hotel where I stayed during my visit there. (The actual Art Hub was a temporary pavilion designed by José Garcia, centrally located in Washington Park—literally a white cube, the interior of which was transformed into a Rubik’s cube of imagery [officially—the “FotoGram@ArtHub”] with its constantly morphing array of Instagrammed images). It reflected the intentions of the biennial’s Director and Chief Curator to reflect both the latest developments in photo-image technology and engage the largest possible public audience both locally and inter/nationally. Judging from the continuously morphing arrays in all the locations where I viewed it, they largely achieved their objective.

The impact Instagram has made on the kind of image-making that falls loosely under the rubric of ‘street photography’ is another issue. In the Hub itself, you had the sense of a flickering kaleidoscopic scrapbook of images: selfies, snapshots intended for friends or family, tourist-y shots of landmarks, vistas, destinations, and (yes) what we might call street photographs—but nothing on the order of what we might expect from the best contemporary, much less ‘classic’ street photographers (e.g., Winogrand, Frank, Klein, Moriyama, Doisneau, Cartier-Bresson); in fact very little that could be considered original or even particularly striking. This is a kind of image-making that has less to do with moment, story, or just document, and more to do with identity or simply the transmission of raw information.

Vogue’s photography director, Ivan Shaw (who participated in one of the panels for the Biennial) commented that it was too soon to judge what might become of the medium, whether formatted narratively or approached more abstractly. But what was immediately striking in the Hub was its modality as an instrument of communication (even language), before visual observation or examination—direct and immediately disposable. For many of us, it’s become essentially an adjunct to Twitter or Tumblr feeds—in other words, social media. In this respect, the Hub became yet another beacon of the culture of distraction.

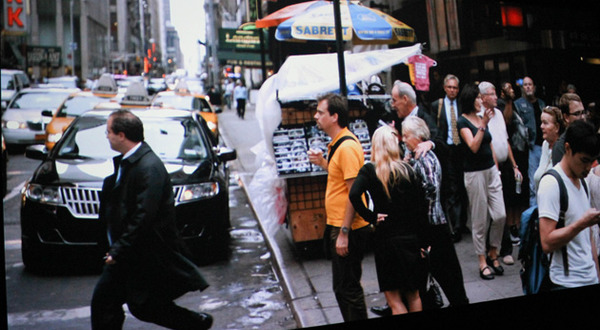

As imagery its power was diffuse at best, or just not there at all—weak. They’re framed and composed formulaically—pat, clichéd. There was very little that might invite us to linger, re-examine, re-consider. And why would there be? This is decidedly not a species of street photography. I’m only guessing, but I’d say somewhere between 25 and 50 percent of the Instagram users rarely take much notice at all of what might be going on around them on a city street, for the simple reason that their eyes are fixed on a screen—usually held somewhere just above waist level or directly in front of them. (How many of us have been struck by pedestrians crossing streets all but oblivious to landmarks, oncoming traffic, or even other pedestrians as they gazed and tapped at digital devices? Sighting them from my car here in Los Angeles, I’m often tempted to hit my horn to nudge them out of their digital obliviousness; but I frankly don’t think it would move them.) Which is not to say more interesting developments won’t come. There’s a great deal of Instagram-ing to one side of the event/social media documentation that’s all about the specimen shot. We can easily imagine future instances crossing between these two categories that may take on micro-narrative or forensic values.

In the meantime, what about the micro-narrative? Or for that matter, the macro-narrative: of a community, a society, a city, its streets and architecture—and the micro-narratives that unfold in plain view (though possibly unnoticed)? How to move those eyes back to the street—which brings me to what was one of the highlights of FotoFocus 2014.

Even as the eyes of a digitally socialized generation are increasingly diverted from the street (alongside other sensory functions effectively out-sourced to digital platforms), many of those streets have a fresh set of eyes upon them, potentially hundreds: mostly electronic, poised behind surveillance cameras, random video/digital cameras mounted on cars and other vehicles, and of course individual phones and digital devices; with still more eyes monitoring them behind yet another field of screens. Eyes On the Street, curated by Brian Sholis for the Cincinnati Art Museum, recontextualizes ‘street’ photography against this backdrop of technological innovation and intrusion, reflecting a more self-conscious, deliberative approach to a class of imagery and documentation that has itself expanded beyond the street and into the realm of what ‘lives and dies’ on it.

Even as the eyes of a digitally socialized generation are increasingly diverted from the street (alongside other sensory functions effectively out-sourced to digital platforms), many of those streets have a fresh set of eyes upon them, potentially hundreds: mostly electronic, poised behind surveillance cameras, random video/digital cameras mounted on cars and other vehicles, and of course individual phones and digital devices; with still more eyes monitoring them behind yet another field of screens. Eyes On the Street, curated by Brian Sholis for the Cincinnati Art Museum, recontextualizes ‘street’ photography against this backdrop of technological innovation and intrusion, reflecting a more self-conscious, deliberative approach to a class of imagery and documentation that has itself expanded beyond the street and into the realm of what ‘lives and dies’ on it.

The work exhibited includes film and video, along with conventional still photography; and among the ten artists included in the exhibition, Jill Magid confronts the realm of surveillance head-on—screen, as it were, to screen—in the 2004 video, Trust. In what seems, alternately, a physical tracing or tracking, an elaborate dance, a kind of mapping and isolation, and as an instrument of pure performance, Magid, ‘partnering’ with a CCTV operator for the Liverpool Citywatch surveillance system, allowed herself to be guided through the city’s streets—for most (or at least some part) of it, with her eyes closed. Michael Wolf’s approach to this domain is more architectural or spatial; yet his photography reflects the transformative, transgressive effects of magnified image and scale. His images move fluidly between the architectural (and abstract) and glimpses, often surprisingly intimate and vulnerable (e.g., Transparent City), of the life pressed up against the glass.

The work exhibited includes film and video, along with conventional still photography; and among the ten artists included in the exhibition, Jill Magid confronts the realm of surveillance head-on—screen, as it were, to screen—in the 2004 video, Trust. In what seems, alternately, a physical tracing or tracking, an elaborate dance, a kind of mapping and isolation, and as an instrument of pure performance, Magid, ‘partnering’ with a CCTV operator for the Liverpool Citywatch surveillance system, allowed herself to be guided through the city’s streets—for most (or at least some part) of it, with her eyes closed. Michael Wolf’s approach to this domain is more architectural or spatial; yet his photography reflects the transformative, transgressive effects of magnified image and scale. His images move fluidly between the architectural (and abstract) and glimpses, often surprisingly intimate and vulnerable (e.g., Transparent City), of the life pressed up against the glass.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia has long explored the human terrain straddling the ambiguous divide of exhibition and exposure, both artistically and commercially, treating his subjects with a kind of hard-edge chromaticism. Here, in his 2001 Heads series, working with a strobe light, his camera peels away the veneers of identity to expose traces of character, even a latent narrative. (But then so much of diCorcia’s work implies a suspended narrative.)

James Nares’ 2011 high-definition video, Street, slows down (but doesn’t quite still) the collective urban street narrative to let the viewer trace, isolate, and linger over the physical movement, the involuntary gesture and unconscious expression, the flicker of sensory or emotional registration. In a matter of seconds, we penetrate an unseen ‘fourth wall’ to unspool and re-frame a fragmentary narrative of street, energy, urban life, human behavior and character. Using very different photographic and framing techniques and strategies, Paul Graham and Barbara Probst (who uses multiple cameras) similarly deconstruct photographic narrative, lifting the veil on a micro-sequence of ‘decisive moments.’

Other artists here work with various exposure (including multiple exposure), cinematic (framing, tracking/crane/steadicam), and lighting/chromatic techniques. This is a relatively compact show; conceivably it could have been somewhat larger. But Solis manages to compass a broad range of imagery and subject matter, insightfully probing the cultural, social, political, aesthetic and technical issues surrounding them. The show also includes work by Olivo Barbieri, Jason Evans, Mark Lewis, and Jennifer West. Elegantly installed in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s beautifully proportioned galleries, the show, not unlike the Nares high-definition video, has the effect of slowing the viewer down, letting us register the impact and implications of each image; to linger and reconsider, to alter our perspectives and probe speculatively beyond surfaces. (In other words, it’s the Anti-Instagram show.) Solis has written an elegant essay to accompany the exhibition—which I would love to see travel. It’s one of the best curated shows of contemporary photography I’ve seen in the last several years.

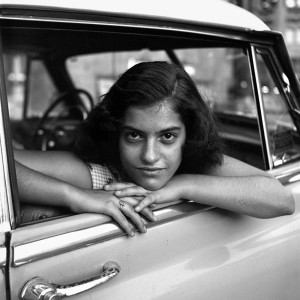

So much has been written about Vivian Maier since her work was first published on-line only a year before her death; and there is little need to add to it here. It’s as if she were not only a great street photographer, but the great under-cover street photographer. She both used the relative anonymity of her service-class position to insulate herself from scrutiny she might otherwise have invited, and her role as a nanny as cover for photography forays into less-familiar neighborhoods. But it wasn’t as if she lost sight of her own identity in the process. (It’s no small tragedy that she never achieved the recognition she deserved in her lifetime.) Kevin Moore’s show for the 2014 FotoFocus, Vivian Maier: A Quiet Pursuit, was largely built around this aspect of her work.

So much has been written about Vivian Maier since her work was first published on-line only a year before her death; and there is little need to add to it here. It’s as if she were not only a great street photographer, but the great under-cover street photographer. She both used the relative anonymity of her service-class position to insulate herself from scrutiny she might otherwise have invited, and her role as a nanny as cover for photography forays into less-familiar neighborhoods. But it wasn’t as if she lost sight of her own identity in the process. (It’s no small tragedy that she never achieved the recognition she deserved in her lifetime.) Kevin Moore’s show for the 2014 FotoFocus, Vivian Maier: A Quiet Pursuit, was largely built around this aspect of her work.

Maier made quite a few self-portraits during the course of her dual career. But there’s a tentative, almost delicate, quality to even the most self-conscious and deliberative self-portraits. More often, she’s engaged in, not so much peeling away layers or ‘walls’ (armor?) in personal identity (her own and her subjects), as in simply observing the layers of transparency and reflection. (There are a number of ‘on-the-street’ self-portraits, where she clearly envelops herself in the reflections and the life of the street around her.) Her self-portraits embrace both the concrete and the ephemeral, some ruminative and verging on the surreal, others almost deliberately abstract. With many of her street subjects, Maier’s approach is oblique and discreet. She’s content to leave the ‘layers’ of identity intact and in place—more interested in observing apparently self-possessed subjects ‘caught in the act’ of ‘performing’ their identity. This is at the heart of her special gift. She captured the street and the city for the real life stage it was and is.