When I initially started hearing the buzz surrounding filmmaker brothers Chapman and Maclain Way’s Netflix documentary series about the Indian guru Bhagwan Rajneesh’s failed attempt to establish a large commune in rural Oregon in the 1980s, I was surprised—hasn’t this story been rehashed a million times? As I began to learn more, I was startled that many commentators, reviewers, my own friends and the filmmakers themselves claimed to have been previously ignorant of the story. A story which, at the time, generated one of the most frenzied media circuses ever surrounding the issues of so-called “cults” and religious freedom in America.

The saga of the city of Rajneeshpuram was seen by many of those connected to the “Human Potential Movement”—the grab-bag of psychological, sociological and spiritual experiments that emerged in the wake of the psychedelic ’60s—as the death knell of the commune phenomenon, and the climax of a deliberate decades-long campaign to delegitimize, destabilize and disempower these politically autonomous experiments in intentional community-building. The success of this strategy can be measured by the cultural amnesia that gives the Ways’ Wild Wild Country its frisson of novelty, and by the default cartoonishness the resulting documentary—as fair and balanced as it tries to be—uses to depict the conflict and its players.

The nutshell spoiler-lite version—and I definitely recommend watching the series, in spite of my misgivings—goes something like this: In 1981, the nonprofit Rajneesh Foundation bought a 64,000-acre ranch in rural Oregon, and immediately began to transform the rugged wilderness into a functional city—eventually including housing for 7,000 people, restaurants, shopping malls, giant meeting halls, a 4,200-foot airstrip, a dam and reservoir, sewage and electrical infrastructure, a public bus system, postal system and fire and police departments. Locals were not amused. Antics ensued, including salad-bar bioterrorism, assassination attempts, election and immigration fraud, and the defection of the Rajneesh’s zany right-hand iron lady, Ma Anand Sheela.

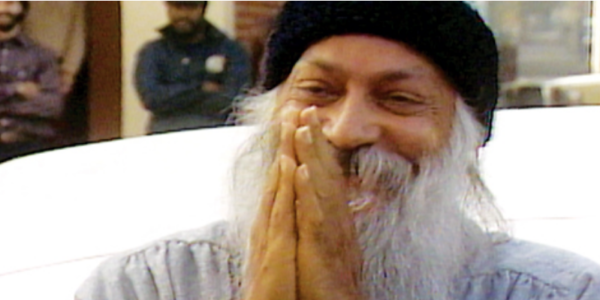

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

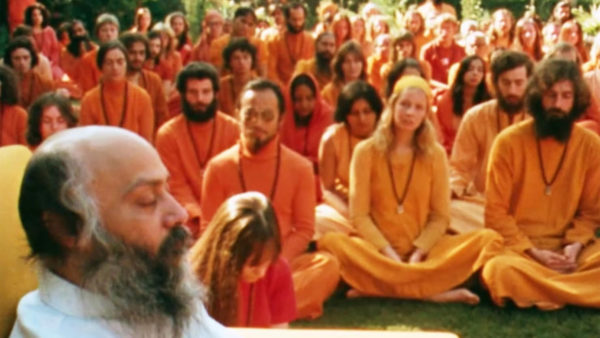

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh was already a famous and wealthy spiritual leader when he moved his center of operations to the U.S. Unusual for his broadly syncretic approach to spiritual offerings—incorporating Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, Christian, Hassidic and Sufi teachings in his system alongside Gurdjieffian exercises and Gestalt psychotherapy— he attracted a massive following of highly educated Westerners, drawn to his anti-authoritarian tone, irreverent humor and emphasis on sexual freedom. “Religion,” he said, “is an art that shows how to enjoy life.”

Almost none of this—apart from the sexual freedom part, of course—makes it into the six hours of old and new footage (brilliantly edited by Neil Meiklejohn into a suspenseful marathon of credibility ping-pong) that make up Wild Wild Country—nor is there any but the most cursory explanation of what exactly the residents of the commune did when they weren’t donating their construction labor or lining up for Rajneesh’s daily Rolls-Royce drive-by blessing. But the viewer comes away with no sense of why anyone would devote their entire life to such a conspicuously unconventional lifestyle, apart from some vague speculations that “everyone wants to feel like they belong.” But Mr. Rogers Neighborhood this ain’t!

This heavy bias towards character-driven, sensationalistic storytelling seems naive; the outcome most certainly disingenuous. I find it hard to believe that Hollywood insiders like the Ways—nephews of Kurt Russell whose only other film was a documentary about their grandfather Bing Russell’s Indie Portland baseball team, the Mavericks—could have never heard about Rajneeshpuram. The implication that the project was inspired by the discovery of a forgotten treasure trove of archival news footage is belied by the perfectly serviceable 2012 Oregon PBS documentary Rashneeshpuram (available for free viewing online at www.opb.org/television/programs/oregonexperience/segment/rajneeshpuram/) which shares many of WWC’s most arresting clips.

But hey, that’s showbiz, right? The creepier thing for me is the filmmakers’ apparent obliviousness regarding the motivation and techniques of thousands of people—millions if you include all the other communal experiments—whose attempts to deprogram themselves and each other from the cult of mainstream consumer materialism were first crushed by bureaucratic and paramilitary coercion, then erased from an official history that only grudgingly acknowledges the Civil Rights Movement, while burying most of the enormous social upheavals of the last century under an avalanche of entertainment trivia. The crazy sex guru and his gun-toting, salad-bar poisoning minions who duped rich hippies into buying him 93 Rolls-Royces, then tried to take over a god-fearing frontier town, is undeniably TV-documentary gold, but lurking beneath that there’s a far more dangerous and exciting story to be told. Hey, that rhymes!

What is art? Can it be the carving of a negative social sculptural space out of the undifferentiated Matrix of late capitalist cultural larb? Can it be the operatic socio-political-spiritual convolutions that ensue? Can it be a blithely propagandistic film documenting the historical moment through an epistemological filter of celebrity gossip? Can it be all of the above? I may know the answers but I can not tell you. You must find the answers for yourself. Start the Journey. It will change your life.